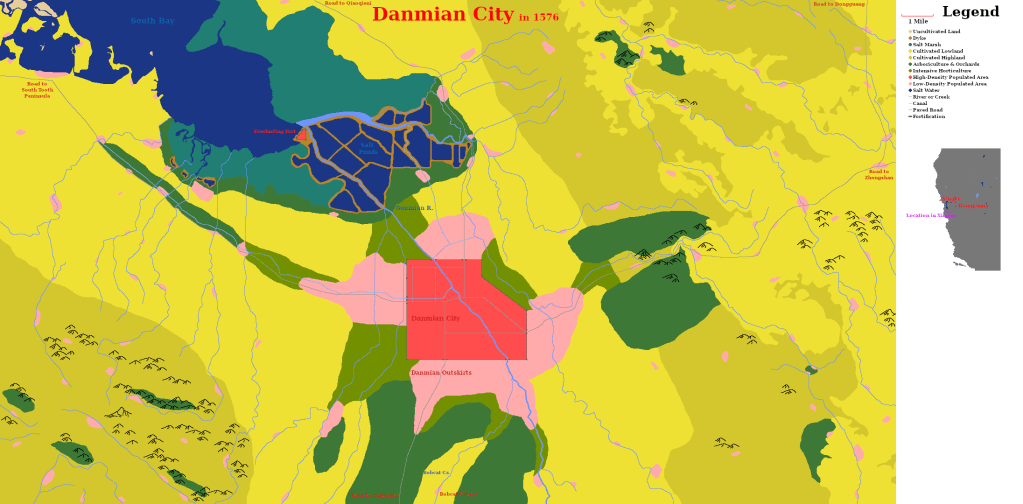

[Maps of the West Coast in 1576]

5.1 – Into the Bay (June 25th – 28th, 1576)

On June 25th, news of the loss of North Tooth Fort reach Ningbo and Dongguang at the same time. Wei Yonglong could barely contain his fury when he heard about his uncle’s poor performance. Wei Xiangyu was banished for five years to the frontier town of Rayong, a Thai colony on Washishu Lake in the Golden Mountains. He returned to Ningbo only a few months before his passing in 1581.

Wei Xiaojia, on the other hand, was exonerated of any wrongdoing, since he’d only been following orders. Far from being punished, in fact, Wei Xiaojia was tasked with gathering a large fleet that could strike at the Mexicans if they entered North Province waters. To do this, Xiaojia had to send letters to all the coastal garrisons ordering them to send ships to Ningbo via the Red-Wen Canal (thereby bypassing the Jaw). Meanwhile, Wei Yonglong recalled his army campaigning in the Pit River Country and began mobilising 10,000 militia to converge on Ningbo.

Over in Dongguang, Bai Guguan was shocked out of his torpor by the fall of the Jaw. Perhaps losing his edge in his old age, it seems Bai hadn’t considered either that New Spain could strike Xinguo with such a large force or that they’d be able to capture the Tooth Forts so quickly. Unlike Wei Yonglong, however, he couldn’t simply withdraw his army fighting the Cloudy Tribes in the Red Rock country. To do so would leave thousands of settlers in the region without protection. Instead, he mobilised even more militia. Including the militia in the coastal regions he’d already called to arms, he now planned to muster a force of 20,000 men, 14,000 of whom would converge on Dongguang, which everyone expected to be the Mexicans’ next target.

And indeed, the primary goal of the Acapulco Expedition was to capture Dongguang. However, there was a problem. Alonso Flores, apparently, was not stellar at reading maps. It didn’t help that the map of the Bay area he’d been given was light on details and his written description of the route to Dongguang was vague. Aguilar was of no help either, since he’d only passed through the area briefly.

What Flores knew was that he was supposed to pass by an island to enter a different section of the Bay, and keep to the south, to avoid entering North River and ending up at Ningbo by accident. The problem was that the Bay is made up of several smaller bays linked together. The Central Bay, where Flores was located, had two major islands, and beyond each of them was a different section of the Bay. Based on his limited knowledge, Flores decided to keep to the south, as he’d been told. Leaving behind 1,000 men and 4 warships to occupy the Tooth Forts, Flores sent a letter to Acapulco with an update on his situation. Then, in the morning of June 25th, he rounded Treasure Island and entered South Bay. This was his first mistake, since Dongguang can’t be reached from South Bay.

Once in South Bay, he sent some of his smaller ships out to forage. Fishing villages lined the shores. Only a few had been abandoned: since everyone believed the Mexicans were headed for Dongguang, the people of South Bay couldn’t believe their eyes when they saw European-style ships flying the Cross of Burgundy sailing their waters.

The same scene played out over and over. A ship would anchor near a village. Men in boats would come ashore, demanding supplies. Nobody in these parties spoke Yue, so they had to get their point across using body language. In exchange for supplies, they offered slips of paper which promised reimbursement once Spain was in control of South Province. Written Spanish looked like chicken sratch to the locals, who were deeply offended by the idea that they would hand over their precious supplies of grain and smoked fish in exchange for some paper with random ink squiggles on it.

What happened next depended on the village elders. The mobilisation of the provincial militia had reduced the number of armed men the villages had on hand, and the ones who were left were a far cry from the well-trained soldiers making demands of them. Not only were the Mexicans better trained and equipped, they also had a warship anchored offshore which could blow the little village to smithereens.

Most villages took the offer. A few resisted, but capitulated after a brief bombardment. In one village, a fight broke out which resulted in the entire shore party being killed. In response, the warship blasted the village with an hour-long cannonade. Another party went ashore where they killed the men who resisted and scattered the civilians who hadn’t already fled. They then took everything they wanted and burned the village to the ground.

While this was going on, Alonso Flores and the main body of the expedition kept on heading south. Their goal was to find the mouth of South River. From there, it was was a simple matter of sailing upriver to reach Dongguang. After sailing in circles for a while, they found the mouth of a river on June 28th. A few miles upriver, they could see a city and between them and it stood one small fort.

5.2 – The Fall of Danmian (June 28th, 1576)

Danmian was a city of 40,000 people situated on the Danmian River. Both were named for the Tamyen, one of the tribes belonging to the larger group of tribes the Xinguans called Coastal People, and was located on the site of one of their villages.

The city was governed by a local magnate named Mao Fulong. As magistrate of the city, he was also magistrate of Coastal Prefecture, of which Danmian was the capital. Mao Fulong had been told about the Mexican ships raiding villages down the length of South Bay, but had chalked them up to paranoid rumours. What interest could the Mexicans possibly have in a city like Danmian? Dongguang had to be their goal, and therefore they couldn’t possibly be on the way to Mao’s city.

News of the unexpected appearance of Mexican ships on the morning of June 28th arrived at Mao Fulong’s home while he was having breakfast and hit him like a sledgehammer. He rushed to climb one of the city’s watchtowers to take a look himself. Total shock set in when he could no longer deny that the Acapulco Expedition was right on his doorstep.

Danmian was totally unprepared for a siege. Defences around the city were light. It had a curtain wall, but it was badly in need of repair after nearly a century of neglect, and the city had grown far beyond it anyway. A small fort—situated north of the city between the mouth of the river and the salt ponds for which Danmian is famous—provided the mainstay of defence with 6 cannons and 200 men. It was named Fort Everlasting: an awfully ambitious label for the rather modest fortification. 4,000 militiamen from the city and its environs had mustered in accordance with Bai Guguan’s mobilisation order, and the city had a garrison of 500 professional soldiers (200 of whom were stationed in the aforementioned fort). Most of the 4,000 militia were camped outside the city cooking breakfast. There was no time for Mao to prepare a defence or call for reinforcements.

Rather than make a stand, Mao Fulong decided to preserve whatever armed forces he could. He ordered all militia and soldiers in the city to immediately withdraw, except for those garrisoned in the fort, who were to hold out against the Mexicans for as long as they had ammunition. Then, following his own orders, he gathered his family and servants and abandoned the city as quickly as possible.

The sight of the magistrate and garrison fleeing while the militia hurriedly packed up camp and prepared to march sent a wave of panic through Danmian. Roads quickly became congested with a stampede of humanity running for the hills or nearby villages. Only those who left immediately managed to make it out of the city: those who stopped to bring some of their belongings with them got stuck in the clogged streets. Some were trampled, some died, and a few women took their own lives to avoid what they feared would be a fate worse than death at the hands of lustful enemy soldiers.

While all of this played out, the Mexican ships remained idle. Alonso Flores was deep in discussion with Benito Aguilar, Marco Melendez, and his other officers about what to do. The city in front of them was not one which Aguilar recognised. It obviously wasn’t Dongguang. That city was on a group of islands in the maze-like South River Delta, this city was on the mainland with no islands in sight. Eventually, it was decided to capture the city and take prisoners who would be able to shine light on where they were and how to get to Dongguang.

Around 10 o’clock, the Acapulco Armada finally spurred into motion. The officer in charge of Fort Everlasting managed to let loose a single volley of cannonfire before his men started trying to escape. He’d placed a squad of his most loyal soldiers at the gate to stop anyone from running away, but they were unable to prevent deserters from rapelling down the walls at the back of the fort, doffing their armour, and fleeing to hide amongst the civilians in the city. By the time the second volley was fired, half the fort’s garrison was gone. At this point, now receiving fire from the Mexicans, the commander decided to destroy the fort in order to deny it to the enemy. His men set a fuse in the gunpowder magazine and ran for the city. As the Acapulco Armada came near the fort, it was blown sky-high, with chunks of rammed earth raining down around the ships.

Now that the powder and ammunition in the fort had been destroyed, the commander reasoned that he had spent all his ammunition—as he’d been ordered to do—and could now retreat with honour, which he did. Meanwhile, Flores’s men went ashore and seized control of all the important-looking building in the city. By noon, Danmian was fully under Spanish control.

5.3 – The City of Danmian (June, 1576)

Danmian straddled both sides of the Danmian river, which flowed through the vibrant of Joyful Heart Valley, at the southern tip of the Bay. In 1576, Joyful Heart Valley was a densely-populated agricultural zone where magnates dominated land ownership with sprawling citrus fruit plantations, which were mainly oranges, of both Mandarin and sweet orange varieties. These were dried and either sold to the Treasure Fleet and other ships to ward off scurvy or exported all over Xinguo and even as far away as Mexico City and Lima, Peru. Oranges from the Danmian area were exported so far abroad that much later, in 1724, while the French explorer Etienne Veniard de Bourgmont was visiting the Padoucas in what would later become Kansas, he was served dried orange slices from a packing crate with Chinese writing on it—quite possibly having been imported from Joyful Heart Valley.

Magnates weren’t the only farmers in the region, though. There was a plethora of small farmers who either rented from the magnates or were often in debt to them. These people mainly grew rice, but also a wide variety of other crops such as millet, wheat, corn, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and all kinds of vegetables, in addition to raising chickens, turkeys, and pigs—lots and lots of pigs, whose meat was salted and also served as a major export.

Besides agriculture, the biggest industry in the area was salt. Salt was produced in the salt ponds, which had been created by clearing away much of the old marshes around the southern Bay area. Most of the production as well as the ponds themselves was owned and operated by the Salt Society of Danmian, a guild of merchants, producers, and investors who’d come to dominate the industry.

Fishing—another of Danmian’s major industries—was done both in the Bay and in the salt ponds themselves, which attracted not only fish but large quantities of water fowls, which were also hunted by the locals.

Of course, there was a problem with that. The Gold Rush of 1504-1514 had given rise to Danmian’s fourth major industry: mercury mining. Mercury was a key element in the refinement of gold ore and continued to be mined in the area long after the Gold Rush was over. Irresponsible mining practices had led to a perrennial problem future generations would continue having to deal with: mercury seeped into all the surface water in the area, contaminating both the Danmian River and the salt ponds. It got into the fish, and therefore into the birds and people who ate the fish.

Sadly, in 1576 the dangers of mercury poisoning were largely unknown. In fact, far from being a negative thing, mercury consumption was seen by many as a positive good. A sect of Daoism—one of China’s “big three” religions/philosophies, with the other two being Confucianism and Buddhism—practiced a form of alchemy in which mercury was believed to be one of the key ingredients in the long sought-after Elixer of Life, which would grant immortality. Easy access to one of their key ingredients made Danmian the biggest centre of Alchemical Daoism in Xinguo. Alchemical workshops both large and small dotted the city where secret societies of alchemists continually experimented with all kinds of dangerous substances in search of the ever-elusive Elixer of Life.

Danmian residents, therefore, suffered from endemic “Wasting Sickness” and “Danmian Madness,” both of which were results of mercury poisoning. The problem did not even begin to be addressed in anything like an effective manner until well into the 20th century.

Danmian City’s Chinese history stretched back to 1439, when the famous explorer Bai Hongjin, founder of Dongguang, came across Joyful Heart Valley during his first expedition. He established friendly relations with the local Tamyen tribe and later built a trading post in one of their villages. Tamyen is rendered in Chinese as Danmian, which became the name of both the river and the city which grew out of the trading post.

The Tamyen were one of a larger group of tribes whom the Xinguans lumped together as “Coastal People.” Of course, the Coastals themselves were mostly gone by the late 16th century, their population having been decimated by disease and a series of wars with the Xinguans in the 15th century—wars which were also civil wars, since some Tamyen and other Coastals sided with the Xinguans against their own kin. A few clung stubbornly to a lifestyle that mixed their traditional ways with the new way of life brought from China, but most of Danmian’s population was descended from settlers who came from the Pearl River estuary region of Guangdong Province back in China.

Danmian’s curtain wall was a decrepit old thing built in the 1450s during the wars with the Coastals. Tension between magnates and peasants in the 1470s had prompted a major overhaul of the walls just in time for them to be used in the 1478 – 1480 Joyful Heart Rebellion. However, it fell out of use in the 1490s, since there were no more serious military threats to contend with. Between 1500 and 1576, the walls were damaged numerous times by earthquakes and were only ever partially repaired. The city itself also outgrew the walls, spilling out the gates and down the roads far beyond them.

During the Anti-Piracy War, piratical activity around the Bay’s coasts renewed the need for defences around Danmian, so the prefect built Everlasting Fort at the mouth of Danmian River. It was a major engineering project, since dirt had to be hauled in to fill in part of one of the salt ponds to create a solid enough base to actually build a fort on top of without it sinking into the marshy ground. Even so, the end result was rather modest; just a walled enclosure and a few towers at the corners enclosing a barracks all meant for a garrison of 200.

5.4 – Prefect Mao Fulong (June, 1576)

When Prefect Mao Fulong abandoned Danmian, he went to the militia encampment on the outskirts of the city, where he took command and led the militia to a location a day’s march upriver where the water was too shallow for the Mexican ships to follow. Here, he ordered his men to fortify the camp and prepare for an assault.

With his authority as prefect, Mao also wrote letters and stamped them with his seal and sent them to all towns and villages in the prefecture, calling all able-bodied men to take up arms and converge on his position. He also sent letters to all the magnates in the prefecture, calling in favours and tapping into family ties to convince them to give him their full support—and to send their armed guards to join his army. How many men would actually answer the call and how useful a people’s militia like this would turn out to be on the battlefield remained to be seen.

Lastly, as Mao dug into his position with 4,300 soldiers and militia and 5,000 civilians in his small, makeshift fort, he wrote one last letter to Bai Guguan informing the governor of Danmian’s fall and requesting reinforcements. He wasn’t expecting a positive response, but it was his duty as prefect to make the report.

Unlike the governorship, prefect positions were not generally passed from father to son. Instead, magnates in the prefecture had to compete for the governor’s attention in order to be appointed to the office. Mao Fulong, born in1512, was one of the richest landowners in Coastal Prefecture, which put him in the class of people called magnates—a term translated from the Chinese phrase “dafu,” meaning big man (magnates could also be called “daren,” big person). This had enabled him to pull the right strings and be appointed magistrate in 1553.

The next year, a Wokou fleet had sailed into the Bay and raided their way down the coast all the way to Danmian. Mao had begged Bai Guguan for reinforcements, but received none. He tried to make a stand with the militia under his command, but the pirates easily scattered them and sacked Danmian. In the aftermath, Mao made plans to build a new curtain wall to protect the city. Bai not only refused, he demanded the magnates of Coastal Prefecture pay an extraordinary contribution (a tax by another name) to help fun the 2nd Anti-Piracy Expedition—which turned out to be an abysmal failure.

Mao was blamed for allowing the Wokou to sack Danmian and was forced to resign under overwhelming pressure. Mao, on the other hand, blamed Bai Guguan for everything.

This was the origin of the grudge Mao Fulong began to cultivate against Bai Guguan.

The second incident to stoke Mao’s grudge was in 1559, when a Wokou fleet sailing down South Province’s coast looted and burned his summer home. Mao’s daughter, who was staying there at the time with her family, was kidnapped along with Mao’s granddaughters: her husband was killed trying to defend them. Once again, an extraordinary contribution was raised and Bai Guguan sent out the 5th Anti-Piracy Expedition.

The 5th Expedition was a joint venture between North and South Provinces. Initially, the expedition was under the overall command of the Northern admiral, who succeeded in finding and rescuing most of the hostages taken in the 1559 raids (including Mao’s daughter and granddaughters). However, the Southern admiral was worried the Northerners would get all the glory, so he split his half of the fleet off and went in search of glory he could call his own (taking the rescued Southern hostages with him). The Northerners returned home safely with the hostages they rescued, but the Southerners got lost and were ambushed. Mao’s daughter and granddaughters were killed in the fighting but the admiral himself was able to escape the trap and return to Xinguo. Mao Fulong blamed their deaths on Bai Guguan for appointing an incompetent glory hound to command.

Relations between Mao Fulong and Bai Guguan cooled over the next decade. Eventually, Mao was able to get himself appointed as prefect again in 1572. The next year, a devastating earthquake hit Danmian. 6,000 people died in the earthquake and another 6,000 died of hunger and disease which followed in its wake as farms which thousands of people depended on for food were wiped out. Orange harvesting was just winding down when the earthquake hit, and so Mao Fulong’s own warehouse full of oranges from his orchard was levelled with the oranges and workers still inside. A dozen people died and more were injured in the building’s collapse.

People, starving and desperate, sold their own children into slavery; a fairly common practice throughout Chinese history. It was that or watch them slowly wither and die. Bills of sale show 5,000 children purchased by slavers in Coastal Prefecture in 1573 and ’74. Rumours of cannibalism spread as well, though they’ve never been confirmed.

Naturally, Mao Fulong appealed to Bai Guguan for help—although by this time, he must already have been skeptical of getting any actual aid. True to his past behaviour, Bai had little to give. South Province’s economy was still recovering from the Anti-Piracy War, Bai Guguan was trying to rebuild his navy after the losses taken when the pirates assault the Teeth Forts in 1569, and he was now engaged in the Cloudy War, which was proving to be more costly than he initially calculated. What was left was mostly being sent north to various Wokou factions to keep them fighting each other. Bai did manage to scrape together a little money to Mao for disaster relief, but nowhere near enough.

Mao was forced to empty the prefecture’s treasury trying to alleviate as much of the damage as he could. Although he’d suffered a great deal personally from the loss of his orange harvest, he dared not use public funds to rebuild his own operation for fear of looking corrupt. Instead, he spent the money helping others to rebuild. Not only that, but he did what a good Confucian gentleman was supposed to do in such a situation: he sold off much of his own personal property, including artwork, expensive clothes, and jewellery to raise funds for charity. His example inspired others to do the same, which enabled the prefecture to recover fairly quickly. Mao’s personal finances were much slower to recover.

Typically, a disaster of that magnitude would be seen as a clear and obvious sign from Heaven that the people in charge (such as Mao Fulong) no longer had Heaven’s mandate to govern and should be removed. Such times were often when popular rebellions broke out. However, through raising charity and emptying public funds on reconstruction, Mao was able to stave off the impression that he had lost Heaven’s mandate.

Whenever anyone asked him why he couldn’t do more, he was quick to pin the blame on Bai Guguan for his underwhelming support for the prefecture. Before long, Mao wasn’t the only one who was beginning to think Bai was unfit to govern.

All that may seem tedious, but it was vital to enumerate in order to illuminate something which is about to become critical: Mao Fulong and Bai Guguan didn’t get along. In fact, Mao hated Bai’s guts. Bai, on the other hand, doesn’t seem to have hated Mao, but he certainly didn’t trust him very much and probably regretted making him prefect.

5.5 – Holding out in Danmian (June-July, 1576)

Meanwhile, having captured Danmian on June 28th, Alonso Flores de Salas y Vargas was discovering that finding out his location was easier said than done. Only the Franciscan Benito Aguilar y Chavez de Sarria could speak the local language, and his vocabulary was limited. What Flores desperately needed was a guide who could speak either Nahuatl or Spanish and show the way to Dongguang. Someone with this specific skillset was not immediately forthcoming, however.

Furthermore, the city was still in a state of panic. Abandoned by their protectors, the civilians were terrified of what fate might await them at the hands of the invaders. These were not idle fears: after capturing what he believed to be the key strategic locations in the city, Flores divided his men in two halves. One half took up defensive positions around Danmian while the other half combed the city looking for food and treasure. Now, this wasn’t a disorderly rape and pillage, it was instead a methodical sacking. Soldiers spread out by companies and squads and searched every building that looked like it might contain anything edible or valuable. Any such objects they found were brought back to the ships and loaded into the cargo bays. Any important-looking people they came across were taken into custody and brought to a large waterfront house which Flores had designated as his temporary headquarters.

That being said, while this was an orderly sacking as far as sackings go, it was a sacking. According to Xinguan records of the event, some 50 people were killed, over 200 women raped or otherwise sexually violated, and several hundred others were conscripted to carry baggage for the Mexicans, as well as 8,000 taels of silver in property damaged or stolen (one tael is equivalent to 50 grams, so a little under half a metric ton of silver).

Undoubtedly, someone in a city the size of Danmian had the language skills Flores needed, but no one wanted to appear to be helping the enemy. If any of the people Flores brought in for questioning spoke Nahuatl or Spanish, they didn’t reveal it. Aguilar had to question them all in Yue; a gruelling task for one as non-fluent as he.

Over the next couple of days, Flores was able to ascertain that he was in a city called Danmian, quite some ways south of where he needed to be. All the people he questioned claimed that they didn’t know the way to Dongguang by water, although several of them mentioned that the road exiting the city to the north eventually led there. Flores didn’t want to take a land route for fear of becoming separated from his fleet. Frustrated at the lack of volunteers, he threatened to start torturing people until someone agreed to guide him through the Bay. Aguilar refused to sit in on torture sessions, however, so that idea had to be shelved.

In lieu of torture, Flores resorted to hostage-taking. He took into custody all the high-class women and children he could find and started demanding aid from their husbands and fathers in exchange for good treatment of the prisoners.

Finally, on July 3rd, a man came forward who agreed to act as an intermediary between the Acapulco Expedition and the people of Danmian. His name was Yao Tuonajiu. Tuonajiu was a loanword from Nahuatl Tonatiuh, which was the name of one of the Nahua sun gods. Despite his name, however, Yao only knew a few words in Nahuatl. He’d been a low-level functionary in the municipal government—a job that involved little more than looking after municipal records and passing orders and memos between offices.

When the order came from Mao Fulong to evacuate the city, Yao had missed the memo by virtue of having had the day off due to a fairly severe cold. By the time he realised what was going on the streets were already packed, so he hid his wife and two young daughters (aged 9 and 3) in a secret room in his house, seated himself in a chair facing the front door, and waited. When the Mexicans broke in, Yao stood up, bowed to them, and showed them around the house—much to their confusion. They stripped his pantry and took him to Benito Aguilar.

During the interrogation, Yao was asked why he looked different from the other Chinese-descendants in the city and he replied that while his father was of Chinese heritage, his mother was a Coastal—which was a flim flam fib, but we’ll get back to that later. Yao was willing to cooperate, but first required guarantees that his family would be well treated. After both Aguilar and Flores assured him of this, Yao returned to his house and showed the soldiers the hidden room where his wife and daughters were still hiding—and with them, the family’s savings in silver coins. Both Yao’s family and his savings were seized by the Mexicans, but the family remained unharmed.

On July 3rd, Yao Tuonajiu agreed to work with Flores and was in turn given his savings back, in addition to being promised a weekly wage, and was also allowed to move in with his family, who were living under guard in one of the waterfront buildings commandeered by the Mexicans.

Now that he had a local working with him, Flores’ first order of business was to re-impose some sort of order on Danmian. He asked who was left of Danmian’s government, and Yao replied it was only himself a handful of colleagues who were even more junior than he was.

“In that case,” Flores is said to have remarked, “you shall be the new government of Danmian.”

Yao Tuonajiu was declared interim municipal magistrate and with that authority, he ordered the suburbs of the city to be abandoned. Flores had plans to shore up the city’s decrepit curtain wall to make it a more defensible location, and he also wanted clear lanes of fire in case of an attack. Both these issues could be resolved with the same solution: the buildings immediately outside the walls would be torn down and the rubble used to perform makeshift repairs on the walls.

If Flores couldn’t make it to Dongguang to drag Bai Guguan out of his home, then perhaps he could force the governer out into the open on ground of Flores’s own choosing. After all, the governor couldn’t accept the occupation of a city the size of Danmian, could he? Holding onto the city would require Flores to have a better idea of his surroundings, so he immediately began sending out parties to scout the area.

These scouts quickly came across Mao Fulong’s fortified camp only a day’s march south of Danmian. Mao’s stirring call to arms had roused the hearts of magnates and peasants alike all across Coastal Prefecture and armed men were flocking to his banner at a rate of hundreds per day.

His sentries drove Flores’s scouts off with crossbows, but now that the enemy knew where he was, Mao decided it was time to take a more proactive approach. There was also the matter of supplies, which were running out as his makeshift fort grew into a shantytown. Mao began sending out parties of his own to requisition supplies from the farms around Danmian and to engage the enemy wherever possible. Of course, the problem was that while Flores had ample cavalry—1,000 of them—Mao had only 50 horsemen; not well-trained soldiers, but simply the relatives and servants of nearby landowners who happened to own horses and had a passing familiarity with using a weapon from the back of one.

The result was a series of clashes over the course of the following two weeks, in which the Mexicans tended to come out on top thanks to their superior mobility. They were able to seize the most favourable ground for a skirmish and retreat when they didn’t like their chances of winning, and they were sometimes able to reinforce an ongoing skirmish, turning possible defeat into a decisive victory. As a result, the Mexicans were able to forage most of the supplies in the area immediately around Danmian. However, they were cautious of staying the night outside the walls, so didn’t stray far.

Even so, Mao Fulong wasn’t wanting for supplies. His letters to all the magnates and towns in the prefecture had the intended effect of stirring the population to action. It helped that Mao continued writing letters and sending them out, detailing the atrocities committed by the Mexicans troops since their arrival, with particular emphasis on their treatment of the women both in the city and on the farms the Mexicans raided for food.

More armed men were still arriving every day bringing food and livestock with them. Women and old folks from the surrounding farms brought their produce, and craftsmen came to offer their services. It wasn’t only the common folk who supported Mao Fulong either. He was a popular man in the prefecture. Ordinary people liked him for his handling of the 1573 earthquake, but the magnates liked him as well: some were connected to him by marriage and others simply thought he’d done well enough by them to be worth supporting. The magnates came with their own armed guards and militias personally loyal to them—including a few hundred more cavalry. Mao’s small force of 4,300 men grew to a formidable army of 6,000 by the middle of July, with an equal number of non-combatants and about as many ducks, donkeys, chickens, turkeys, and sheep as humans.

In addition to all this, Mao received a letter from Huế Thành Học, prefect of the Hue Triangle. Having heard of the death of his cousin Huế Bảy Thắng in the Battle of the Jaw, Thành Học was on the path to revenge: he pledged an army of 10,000 men to help Coastal Prefecture drive the Mexicans out. However, he was still weeks away from mobilising, and then he’d have to march to Danmian.

From Dongguang, Mao only received orders to keep the invaders occupied for as long as possible while Bai Guguan raised an army to deal with them properly.

On July 15th, Mao Fulong held a council of war together with the militia leaders, government officials from other parts of the prefecture, and magnates who’d brought their own militias with them. Some of the officials and magnates argued that they should sit tight and wait for Huế Thành Học to arrive with reinforcements. All of the militia leaders, however, disagreed with that notion and argued they should instead attack. Coastal Prefecture couldn’t rely on others to save them or do their fighting for them. No one had come to save them in 1573, and just like then, the prefecture would have to save itself.

Mao favoured waiting for Flores to make a move, and potentially negotiating with him to leave the prefecture so they wouldn’t even need to fight.

Notably, no one suggested they wait for Bai Guguan to come with the provincial militia: it seems no one took seriously the notion that he might actually bother to show up.

Arguments continued late into the night until everyone finally went to bed without having come to any firm conclusion. The next morning, however, the decision was made for them when word reached them that the Mexican army was sallying forth out of Danmian and headed directly toward Mao’s camp.

5.6 – Battle of Bobcat Creek (July 16th, 1576)

Mao Fulong wasn’t comfortable with the idea of trying to withstand a siege within the earthen ramparts of his makeshift fort. Not only were the defences of questionable worth in a serious battle, but it was full of as many civilians as soldiers who could get killed in the crossfire of a clash and would rapidly deplete the meagre supplies he’d managed to stockpile.

Since he couldn’t hold out, Mao decided to meet the enemy in the field. He didn’t have a firm estimate of the size of Flores’s army, but he was reasonably sure it was around the same size as his own force. And indeed, he was correct: Mao had 6,000 armed men while Alonso Flores had 6,200 (1,000 had been left at the Teeth Forts and 800 in Danmian). The problem for Mao was quality. Flores’s men were trained soldiers, some of them veterans of conflicts back in New Spain (the Chichimeca War was still ongoing in the Bajio region and the northern frontiers were being pushed ever further north). Mao’s men were mostly militia—and that was a generous descriptor for some of them. There was also the fact that the Mexicans had matchlock muskets, which were only just now (in the 1570s) in the process of replacing older gunpowder weapons back in China (thanks in no small part to the efforts of the famous General Qi Jiguang): Xinguo had no experience with matchlocks except for the 1548 Battle of Acapulco.

Nevertheless, he decided to take his chances. Mao ordered his men to strike camp, leave the civilians behind, and get marching. By late morning on July 16th, the army left camp closely followed by river barges carrying their supplies. Both armies had a general idea of where the other was, but they were starting a day’s march away from each other and that meant that as soon as they got moving, they couldn’t be sure of the other’s exact position. Flores was heading south on the paved road to Indrapura, but Mao was marching north along the banks of the Danmian River so that he could stay close to the barges loaded with his supplies. This put Bobcat Creek—a fairly substantial tributary of Danmian River—between them.

The two sides only realised the creek was between them when, at around mid-afternoon, skirmishers form both sides spotted each other and spent an hour trading potshots across the creek. When Mao was informed that Flores was across the creek from him, he realised Danmian must be lightly defended and thought this could be his chance to seize the city and deprive Flores of a base to work from, as well as separating him from his fleet. Knowing he would have to cross the Bobcat to get to Danmian, Mao instructed his supply barges to beach themselves and wait for his return while he raced ahead with his army toward the nearest bridge. Flores, meanwhile, was also informed of the skirmish at the creek. His scouts had informed him of the locations of all the bridges in the local area, so he knew exactly where he had to be to head off Mao.

And so it was that both armies arrived at the small community of Bobcat Village, home of the bridge in question. The village’s inhabitants had abandonded it the day Danmian fell, when they saw the provincial militia strike camp and march south in a panic—in fact, they’d been among the first people to arrive at Mao’s makeshift fort, and the men of the village were now marching in his army. Bobcat Village consisted of a series of houses straddling both sides of the creek and surrounded by rice paddies and citrus orchards.

Mao’s army arrived first, but not by much. A vanguard force of 600 provincial militiamen had just finished crossing the bridge when they spotted a column of Aztec warriors emerging from an orange orchard. They were repslendent in padded cotton armour and feathered headdresses with feathers hanging from their shields and macuahuitls hanging from their belts and spears in their hands. In the village, Mao’s militiamen formed up and advanced to the village outskirts. The Aztecs accepted the challenge and charged the Xinguan line. At first the Xinguans held firm, but then New Spanish musketeers arrived. The Aztecs withdrew, which allowed the musketeers to fire a volley at the Xinguans: this nearly broke them, but just then reinforcements crossed the bridge in the form of a mixed unit of pikemen and crossbowmen, who returned fire on the musketeers while the Aztecs made another charge.

More Mexicans arrived and another wave of Xinguans crossed the bridge. At this point, however, it was getting late and Mao didn’t want to risk his men being stuck on the wrong side of the creek overnight. He ordered a withdrawal. With his crossbowmen and archers lined up on his side of the creek forcing the Mexicans to keep away from the bridge, his men were able to withdraw safely. More and more Mexicans arrived. Trying to storm across the bridge now would be suicide.

5.7 – Making for Dongguang (July, 1576)

However, Mao Fulong had one more play to make: negotiation. Therefore, he took a small party up to the bridge, staying out of musket-range, and waved a white flag. After a short wait, a white flag was waved back and a small party approached the opposite side of the bridge. Both sides ordered their men to withdraw well away from the creek, and then at last they met in the middle of the bridge.

On the Mexican side were Alonso Flores, Benito Aguilar, and Yao Tuonajiu (according to his own later account, Juan de Oñate was there as well). On the other side were Mao Fulong and a certain wealthy widow by the name of Xochiatlapal—rendered in Chinese as Huochiyaqiepao, or Huochi for short. Huochi was a very important old widow who had presented herself to Mao Fulong during his stay on the banks of the Danmian River. She was known throughout the area as “Mei Nai,” short for “Meixigou Nainai,” or Mexican Granny.

Many, many years earlier, a merchant by the name of Yao Xueqiu had made it big trading goods between South Province and the Aztec Empire: so successful was he that a local notable in one of the Aztec colonies on the coast in which he traded offered his daughter’s hand in marriage to Yao Xueqiu. The wedding was in January 1519: approximately one month before the voyage of Hernando Cortes, which ultimately resulted in the Spanish conquest of Mei Nai’s homeland. As a result of Spain’s invasion, Yao Xueqiu decided to find a different occupation. He took all the money he’d saved and bought a spacious estate some 25 miles south of Danmian, where he settled with his wife and her family, who fled to Xinguo after the fall of the Aztec capital in 1521.

As you may have already guessed by the name, Yao Tuonajiu was the third son of Yao Xueqiu and Mei Nai. By 1576 Xueqiu was long dead, but Mei Nai—who was probably around 73 years of age—had proven to be more than capable of managing the estate on her own. When she heard that Danmian had fallen and, furthermore, that her youngest boy was working with the invaders, she took her personal guards, armed servants, and the militia from the local area, led them to Mao’s camp, and offered her services as an interpreter. Naturally, she was fluent in both her mother tongue—Nahuatl—and Yue, and reasoned that the Teotl (a nahua word for something extraordinary which they applied to the Spaniards: by all accounts, Mei Nai resolutely refused to call the Spaniards Mexicans, presumably because that was derived from her people’s word for themselves and she didn’t want to associate it with the conquerors) would have at least one Nahuatl speaker with them. Indeed, they had many Nahuatl speakers, given half the foot soldiers in the army were indigenous, and many of those were Tlaxcallans and Aztecs.

We have two records of the meeting. One was written by Juan de Oñate, who claimed to be holding the white flag for Flores, while the other was written by Mao Fulong’s secretary Zhou Xiang (no relation to the later, much more famous Zhou family in Xinguo), who was also present at the meeting. In both accounts, it is recorded that, upon seeing his mother, Yao Tuonajiu’s eyes grew wide and he exclaimed,

“What are you doing here?”

To which she responded,

“What am I doing here? What are you doing here? Slept in again and missed the evacuation order, did you?”

“I was sick—”

“Keep your mouth shut while your mother is speaking, boy! Your grandfather would be rolling in his grave if he could see you now—”

Mei Nai’s Yue, which was normally flawless, broke down into a heavy Nahua accent before descending into full-on Nahuatl at that point, which no one present understood except Benito Aguilar. When Flores asked the monk what she was saying, he looked flustered and replied,

“It is not for our ears.”

When Mei Nai ran out of breath, Mao Fulong took the opportunity to jump in and take control of the situation. He kindly suggested that Mei Nai could handle family matters in private at a later date and she reluctantly agreed.

With that matter put on the back burner, the two sides were eager to discuss the real business at hand. To begin with, the men on either side introduced themselves and their reasons for being there. According to Juan de Oñate, Flores said (in Spanish, translated into Nahuatl):

“I am Alonso Flores de Salas y Vargas, commander of the Acapulco Expedition by the grace of God and of His Majesty King Felipe II. I am here to overthrow the tyranny of the rulers of this land and bring it under the grace of God and the authority of the Spanish Crown.”

According to Zhou Xiang, what Mei Nai said (in Yue, via translation from Nahuatl) was this:

“I am Alonso Flores from Salas and Vargas, commissioner over the Acapulco Expedition in the name of Heaven and the Second King Felipe. I am here to overthrow the rulers of this land and restore the grace of Heaven upon it, by the authority of the Teotl King.”

There have been a great many miscommunications throughout history. Some are of epic proportions, others minor. Some have been a result of a failure to ask for clarification, and some have even resembled high school level drama but with earth-shattering implications. Scholars have long debated the origin of the miscommunication. Perhaps Benito Aguilar wasn’t as good at speaking Nahuatl as he thought, or maybe Mei Nai’s Nahuatl had gotten rusty after living most of her life surrounded by Yue-speakers. It’s possible one or both of them fudged the translation slightly for some reason.

Whatever the case may be, what Mao Fulong seems to have understood was that Flores had come to overthrow the (in Mao’s eyes) evil and incompetent tyrant Bai Guguan in order to restore Heaven’s blessing to South Province and ensure a more prosperous future—and all as a gift from the King of Meixigou. Of course, he must have realised such a gift wouldn’t be for free, but the very idea of a foreign army coming to overthrow the governor for whom Mao Fulong had so much animosity dating back so many years made the prefect positively giddy. It allowed him to dream dreams and think thoughts he never would’ve dared marinate on before.

Mao Fulong asked for confirmation that Flores was indeed here to overthrow Governor Bai Guguan, to which Flores replied in the affirmative. Mao went on to remark that a new governor would soon be needed.

Flores raised an eyebrow, allowed a smirk to grace his face, and (according to Zhou Xiang) replied rather vaguely: “Perhaps.” (According to Juan de Oñate, however, he replied: “Yes.”)

That was all the confirmation Mao Fulong needed.

“It is indeed high time for Bai Guguan to be removed from power,” he stated bluntly.

Mei Nai remained silent, staring at Mao. Mao glared at her and told her to translate what he said. When she finally translated it (rendered roughly the same in Oñate’s account), Aguilar’s mouth fell open. When he translated into Spanish, Flores squinted at Mao, apparently unsure of what to make of such a statement.

What was meant was exactly what was said. Mao said as much when prompted to clarify. He went on to explain that Bai Guguan was hated by both himself and the whole of Coastal Prefecture (“hated by all under Heaven,” In Oñate’s account), that he’d lost the mandate of Heaven (given as the “grace of God,” in Oñate’s account). If the Mexicans were to get rid of him, far from shedding any tears, all the people of the Coast (“All the people of Xinguo,” according to Oñate) would rise and cheer as one.

And so, as the sun set on Bobcat Creek and night deepened around them, three men and one woman stood discussing treason.

Nothing firm was agreed to that summer night of July 16th 1576 on the bridge except that further meetings would be held in a few days in Danmian. Both sides returned to their camps. The next day, the Mexican army withdrew back inside the city walls of Danmian.

Meanwhile, Mao put the idea across to the other magnates of Coastal Prefecture that Bai Guguan had to be removed from power: they responded positively, but asked what that had to do with the fact that a foreign invader was occupying the prefectural capital.

“Simple,” Mao answered. “They’re going to help us.”

Rather than an uproar, this elicited murmuring and curious glances—Mao Fulong grinned. Secretary Zhou Xiang wrote:

“It took no great effort to bring the magnates onboard with the plan concocted the night before.”

Free to cross the bridge, Mao’s army did so and camped near the city. Mao Fulong collected an entourage consisting of an honour guard, Zhou Xiang and other prefectural functionaries, a gaggle of magnates from the area, and of course Mei Nai: together, they entered Danmian and proceeded on to the prefect’s offices on the banks of the river near the centre of the city. There, they were met by Alonso Flores and with him were Marco Melendez, Benito Aguilar, Yao Tuonajiu, and a number of his officers. The topic of discussion: treason.

A plan was hashed out. The Acapulco Expedition would re-embark on their ships and sail up to Dongguang while Mao Fulong took his army to Dongguang overland. And once there—ah, but that would be spoiling a good story.

Flores had two concerns. First, he still needed a guide to show him the way to Dongguang. Second, he needed to know he could trust Mao not to stab him in the back. Mao Fulong grinned and said,

“Two problems, one solution.”

Zhou Xiang was the solution. Having often carried reports to the capital as part of his job as the prefect’s secretary, Zhou knew the way very well. And, in addition to that, he was also Mao’s sister’s son, making him the perfect candidate to act as both hostage and guide.

And so Mao left Zhou Xiang and Mei Nai in the company of the Mexicans and returned to his army. There, he announced that the Mexicans had agreed to withdraw from Danmian, but were heading north to Dongguang. It was their duty to help defend the provincial capital, so they would be marching to reinforce it. Not everyone was happy with this. Many of the men who’d joined Mao’s army were only there to defend their prefecture. Around 2,000 men simply left. Meanwhile, Mao sent men to retrieve his supplies loaded onto the barges that were still sitting on a Danmian River beach somewhere upstream while others were sent to the makeshift fort to tell the people there to disperse.

That very afternoon, the Acapulco Expedition sailed out of Danmian with Zhou Xiang, Mei Nai, and Yao Tuonajiu and his family all aboard. Mao reoccuppied the city and spent the remainder of the day setting things in order. He also began disseminating his own version of the events that had just occurred by paying people to spread rumours of a great victory among the orange trees on the banks of Bobcat Creek which spooked the Mexicans into withdrawing and heading for Dongguang. He made sure to add the detail that the victory at Bobcat Creek was thanks to his own command expertise.

The following morning (July 18th), his supplies arrived along with people from the makeshift fort who wanted to stay with the army. Late that morning, the army marched north on the road to Dongguang. It was a paved road: Mao marched his army hard and left his supplies and civilian hangers-on strung out along the road behind him, so they covered the distance of approximately 60 miles in just three days, arriving in the early morning of July 21st. The army, at this point consisting of 4,000 men with very little baggage and few camp followers formed up outside Dongguang’s south gate in parade formation.

Up to this point, we’ve been discussing what came to be known as the Danmian Campaign: the part of the Warehouse War that took place in and around that city. With the arrival of Mao Fulong’s army at Dongguang, a new phase of the war had begun: the Dongguang Campaign.

At some point between making camp on the banks of Danmian River and the Battle of Bobcat Creek, the soldiers and militia under Mao Fulong’s command had taken to calling themselves Mao’s Lances, spelled 毛矛 in Chinese, and pronounced Máomáo in Mandarin, but it was mou˨˩maau˨˩ in Yue. Either way, the near-identical pronunciation was deliberately alliterative. By the time they reached Dongguang, everyone was calling them the Maomao.

[Next]

Leave a comment