[Maps of the West Coast in 1576]

6.1 – Fortress Dongguang (June-July, 1576)

The city of Dongguang was one of the oldest in Xinguo. In the 1430s and ’40s, the famous explorer Bai Hongjin (founder of the bloodline who would rule South Province) established a number of settlements on the coast while his rival Wei Shuifu was doing the same in the north. Earthquakes destroyed most of these in the mid 1440s. Both explorers noticed that the inland areas suffered from earthquakes less often, so they decided to focus their efforts there.

However, there was a problem. At the time, the southern Valley was dominated by the Youkuci tribes, the most numerous of all the indigenous nations in pre-contact Xinguo, and they had already attacked Bai Hongjin during his first expedition into the Valley. Bai needed a location away from the earthquake epicentre on the coast, but also secure from Youkuci attacks. The solution was to purchase land from the Miwoke, a group of tribes whose territory extended from the coast of East Bay through the South River Delta, across the plains and up into the mountains.

Meanwhile, Wei Shuifu wanted to found his city on land belonging to the Batewan, the southern third of a larger group of tribes called the Wentu.

Therefore, in 1449, two embassies were formed: one of Miwoke and one of Batewan, both representing villages in the Delta region. They crossed the Pacific and made it all the way to Beijing, where they met the emperor. They signed the Treaty of Great Peace, in which China promised shiploads of iron tools and silk in exchange for tracts of land to build settlements on. With the treaty signed, the emperor issued a decree formally creating North Province and South Province and named Wei Shuifu and Bai Hongjin as their governors.

Later that same year, the embassies returned to Xinguo alongside the newly-minted governors and a slough of settlers. Upon their return, Ningbo and Dongguang were founded.

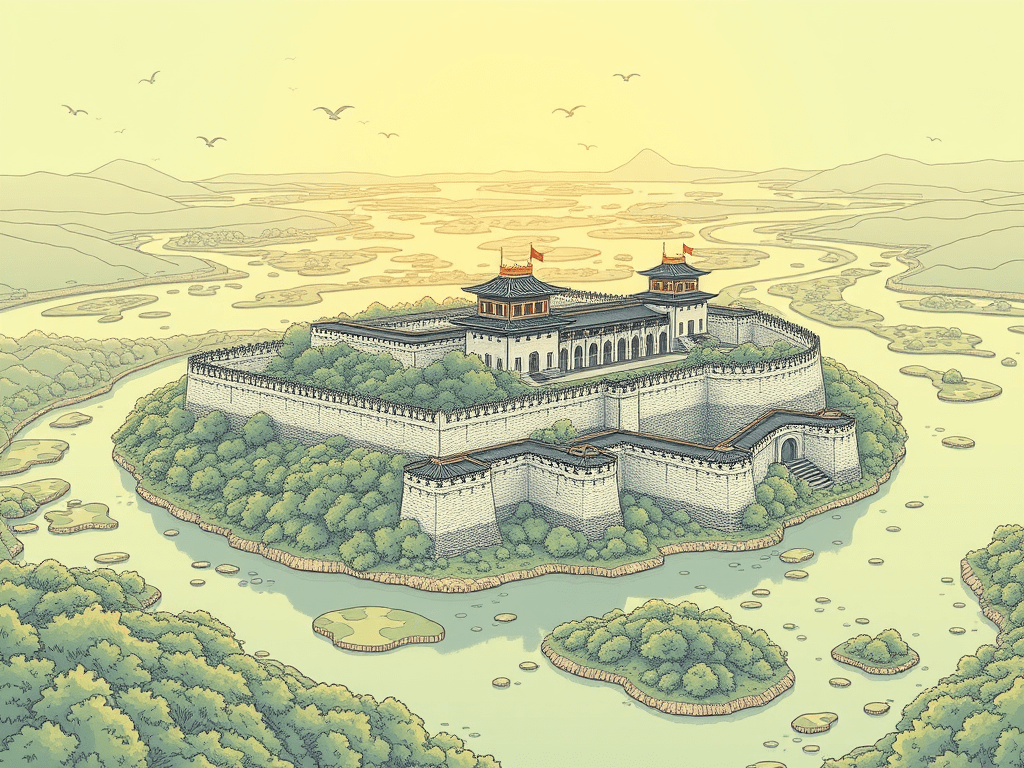

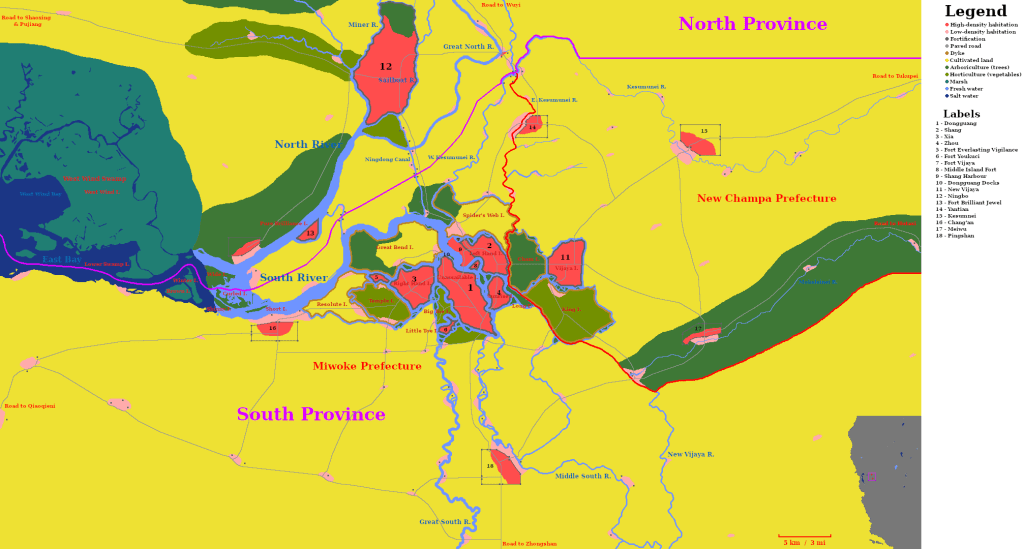

Two great rivers drain the Valley and the western side of the Golden Mountains into the Bay. Those rivers were dubbed North River and South River, sometimes called Wei River and Bai River, after Xinguo’s first two great explorers. They almost meet each other, but then swerve west and converge where they both flow into the Bay. Thus, the two rivers from a single delta region. Bai River splits into many branching streams, forming a maze of waterways splitting and reconverging around an array of islands before they all ultimately reconverge just before reaching the Bay. At the centre of these islands is where Bai Hongjin opted to place the foundations of his settlement.

Throughout the years, Dongguang has always struggled with flooding. The delta isn’t a great spot for a city for that reason: however, concerns about both earthquakes and Youkuci attacks had dictated its location. To combat the floods, a massive dyke-building project was undertaken in the 1470s. All the major islands were colonised by this time, so they all had dykes built around their perimeter. Unnassailable Island, where Dongguang was built, had a defensive wall built on top of the dyke.

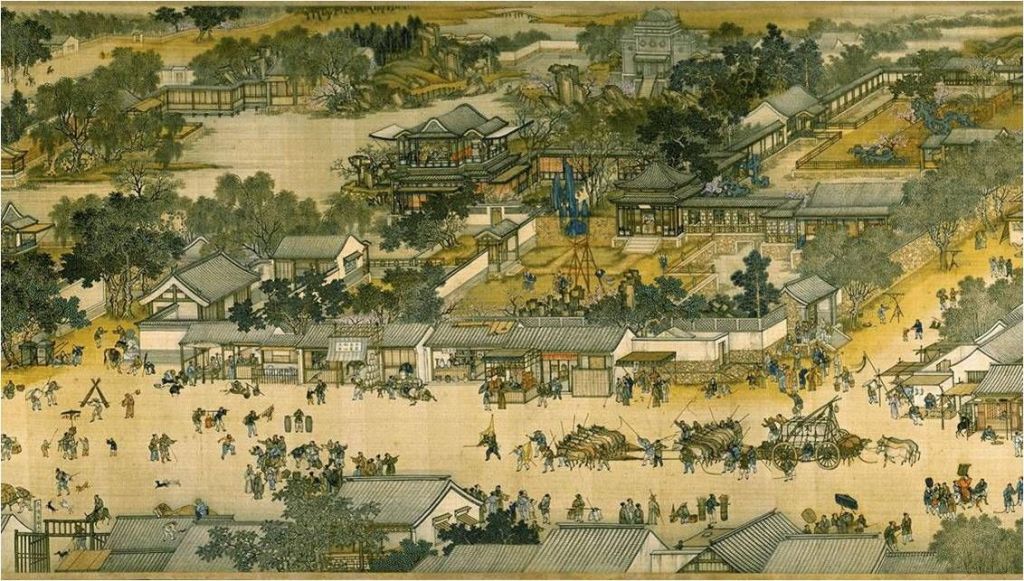

More years passed and Dongguang grew to the point where its population could no longer be contained by one island. Neighbouring islands grew into cities in their own right with their own defensive walls atop their dykes. By 1576, there were five separate cities, each on its own island, its own wall, and its own municipal government. These were Dongguang, Xia, Shang, Zhou, and New Vijaya (called Xin Weijiaya in Chinese). New Vijaya was founded in 1471 by Cham refugees fleeing the fall of Vijaya back in Champa, which was located in what’s now south-central Vietnam. It was the capital of its own prefecture, New Champa, and enjoyed substantial autonomy from the central government.

The other four cities were overwhelmingly Chinese from the Pearl River delta region in southern China, where Bai Hongjin was from (although Shang had large Vietnamese and Zhuang minorities which persisted as distinct communities into the 17th century and, to a lesser extent, retain a distinct subculture to this day). Xia, Shang, and Zhou, by the by, were named for the three semi-legendary (and, in the case of Xia, probably entirely legendary) dynasties of China that predated the Qin Dynasty, which was the first to use the traditional title of Huangdi, or Yellow Emperor. Shang served as the primary port (and, therefore, the actual destination of the Treasure Fleet before its terminus point was switched to Ningbo), with port facilities located outside the city wall in full view of the cannons on Dongguang’s wall just across the river.

In total, the population of all five cities was 80,000 in 1576, making this one of the most heavily populated urban zones in North America since the Spanish conquest of Mexico and resultant de-urbanisation of that region.

In the event of an invasion, all four cities were mutually supporting. Anyone who attempted to seize Shang by water would come under withering fire from Dongguang. Anyone who tried capturing Dongguang first would find themselves surrounded and cut off by the fleet stationed in Shang. Zhou was farthest upriver of the four and was unreachable without first silencing the defenders of Dongguang and Shang. Xia was most vulnerable to an attacker approaching from the Bay. Two branches of the river provided access to Xia from the west. The southerly route was narrower, shallower, and had two stone bridges crossing it. These two bridges were deliberatley built too low to allow the masts of large vessels to pass underneath them, allowing for small-scale local traffic only. Thus, if an attacker wanted the support of their larger vessels (which was necessary to capture Dongguang and Shang), they’d be forced to take the northerly route, which was protected by the fortress-island of Everlasting Vigilance. Two other fortress-islands protected other approached to Dongguang and Shang, and a fourth stood in the river between the capital and its port.

This was Fortress Dongguang. This was what Alonso Flores needed to capture if he wanted to conquer Xinguo in the name of God, Glory, and Gold, and this was what Mao Fulong needed to capture in order to overthrow the hated Governor Bai Guguan.

All that being said, Fortress Dongguang had a problem: manpower. Bai Guguan had given the order to muster provincial militia in all the coastal prefectures and New Champa on June 21st. Miwoke Prefecture, which contained Dongguang, should’ve yielded 10,000 men. Between that and New Champa’s muster, plus professional soldiers in nearby garrisons, and calling in favours from magnates in the area, Bai Guguan had expected to have an army of 20,000 men in a few weeks. Instead, over the course of the next two weeks all he was able to scrape together was 3,000 provincial militiamen, plus 1,500 armed servants loyal to local magnates and the garrison of Dongguang and its neighbours, which totalled 1,200 professionals, all for a grand total of 5,700 armed men.

For defending an area as well-fortified by man and nature as Dongguang, this was a comfortable number. But where were all the rest? The answer to that is simple: it turned out that, in the wake of the repeated failures of the Nine Anti-Piracy Expeditions (and resultant casualties), service in the provincial militia had become deeply unpopular. Draft-dodging had been hard during the war, when squads of soldiers from the professional army were going out and rounding up men to be conscripted for the expeditions, but after the post-war demobilisation, the central administration hadn’t paid close attention to the rosters of names they were being given by county magistrates. As a result, it became easy to bribe the county magistrate to register the name of a dead relative or an entirely fictitious person in order to avoid militia conscription.

Meanwhile, New Champa had mobilised its share of the provincial militia, but was keeping them all in New Vijaya rather than sending them to join Bai’s army. Prefect Pâl Karutdrak—a man known for his paranoia—had the city on lockdown with only essential traffic being let in or out. Between New Vijaya’s garrison, the militia, and magnates’ men, Pâl had some 4,000 men constantly patrolling the walls of his city. Whenever Bai Guguan sent messengers to request Pâl’s presence in Dongguang, the guards yelled in broken Yue that the prefect wasn’t seeing any visitors.

In pursuit of more men with weapons to stand on his own walls, Bai Guguan issued a decree ordering a temporary universal conscription in Miwoke Prefecture: he sent soldiers (not provincial militia) into the countryside to enforce it. Bai’s men visited all the villages within twenty miles of the capital and read out Bai’s decree. Reactions were not positive. Riots broke out more than once. Bai’s men, clad in lamellar and wielding fire lances, rocket arrows, glaives, and two-handed swords, quickly quelled any such violence and they weren’t shy about meting out violence of their own. It isn’t clear exactly how many were killed or wounded, but it was likely between 10 and 30 across six separate riots. The end result, however, was that Bai got the men he wanted. Even if they had to be dragged kicking and screaming, an additional 5,000 men were brought to defend the walls of Dongguang and neighbours.

Still, it was late July by this point and Bai had only half the hoped-for 20,000. He began sending men further afield to conscript even more men and turned his attention to New Vijaya. Rounding up men from the villages was all and well and good but they were likely to run at the first sign of trouble. If he could get the Cham prefect to come out of his shell, Bai might be able to put together a decent field army.

Those were the thoughts on his mind as mid-July wore on when rumours started reaching the capital. Bai Gugan was, of course, well aware that Danmian had fallen to the invaders, but he’d heard nothing further. Now, rumours swirled that a great battle had taken place. Many a be-feathered Mexican had been killed in a battle in an orange orchard. Mao Fulong had liberated Danmian and the Acapulco Expedition had fled. Word was that they were finally headed for Dongguang.

Then, on July 20th, word reached Bai Guguan that “all the armed men” of Coastal Prefecture were marching for the capital. That was good, although Bai had misgivings about Mao Fulong and hoped the prefect wasn’t leading them himself. He expected them to arrive in a day or two, but the next morning a messenger interrupted his breakfast to inform him that the Coastal Prefecture’s army was on the far side of the city’s south gate bridge waiting for permission to enter Dongguang.

6.2 – Double-Crossed (July 21st – 22nd, 1576)

Bai Guguan was annoyed when he learned Mao Fulong was indeed in personal command of the army outside his gate. Bai didn’t like or trust Mao very much: nevertheless, he knew Mao was good at his job (which was why he’d appointed Mao as prefect) and he needed more men to defend Dongguang so he sent orders for Mao to enter Dongguang and split his forces between Xia and Shang.

As Mao was entering the city, two middle-aged men were entering as part of his army. They were the Yao brothers; Yao Guadimo and Yao Yicaoqi, the older two sons of Mei Nai. Before parting with Mao to join Alonso Flores and the Acapulco Expedition, Mei Nai had given very specific instructions to her sons and they swore an oath to see it done. Now that they’d entered Dongguang, it was time to make good on that oath. Slipping away from Mao’s army, they made their way to the governor’s palace at the centre of the island. Once there, they told the guards they had urgent news about the Mexican expedition which they needed to give to Bai Guguan. The guards relayed this message inside and were told to usher the Yao brothers in.

Bai Guguan was in the process of reviewing the city’s defence plan with a number of other provincial and military officials. The Yao brothers were ushered in and introduced themselves as the sons of Huochiyaqiepao, the last free last Aztec, who had made them swear to give Bai a warning. Then they dropped a bombshell on the gathered officials: Mao Fulong was working with the Mexicans and had come to Dongguang in order to betray the city from the inside out.

This caused an uproar among the officials. Every man had his opinion and felt everyone needed to hear it. Some didn’t believe the Yao brothers while others said it was just like that sleazeball Mao to betray the whole province. Bai, meanwhile, only studied the two men in silence. Eventually, the hubbub died don as all eyes turned to the governor. Bai dismissed the Yao brothers and turned to his officials.

“I will send Mao away on a mission… outside the city. We need not let him in the walls again.”

With that, a new order was written up and given to a runner, who went in search of the prefect. Mao Fulong was in the process of dividing his army in two and was sending half away to Shang when the messenger arrived and handed over the governor’s new orders: Mao was to take his army out of the city again and go to New Vijaya. There, Mao would either persuade Prefect Pâl Karutdrak to send half of his men to reinforce Dongguang or arrest the prefect and bring half the Cham army back to Dongguang himself. Baffled, Mao asked why the sudden change of heart. The messenger shrugged and went on his way.

This was a disaster for Mao. Potentially, this one order could ruin everything. Alonso Flores was due to arrive the next day (July 22nd): Mao had to be ready by then. However, he couldn’t just start attacking Bai’s garrison here and now. An adjustment was needed for the plan to work.

Mao’s army was currently strung out in several columns along the main road through Dongguang. Immediately around him, however, was a body of men he knew he could trust: Danmian City’s garrison of soldiers from the professional army. Technically, they were loyal to the emperor back in China first and to the governor of South Province second. In practice, however, those figures were far outside the scope of these men’s daily interactions. Put simply, they didn’t know the emperor or the governor, but they did know the prefect. Furthermore, the prefect was responsible for making sure they got fed and paid on time—and Mao had never let them go hungry or let their pay fall into arrears (except in the aftermath of the 1573 earthquake). As such, he’d already confided in them what their real mission in Dongguang was. Now, with orders to vacate the city immediately, he selected 200 men and gave them new orders. Doffing their weapons and armour, they split up into squads and disappeared into the city. Meanwhile, the rest of the army marched out of the gates as ordered.

Marching in and out of the city ate up quite a bit of time, so it was mid-afternoon by the time he was on the far side of the south gate bridge again. At this late hour, Mao Fulong told the guards at the gate that it was too late to march to New Vijaya (which was about twelve miles away, taking into account the route he’d have to take: more than a half-day’s march). And so, he informed them not to be alarmed, but his army was going to camp outside the gate for the night.

The guards, who had presumably not been informed that Mao was under suspicion of treachery, shrugged and went back to their duties.

Mao dispersed and pitched their tents in the fields among rows of bok choy and yams. Local farmers were none too happy about this and came to Mao to complain, but he brushed them off, stating that he was acting under the governor’s orders—and anyway, he’d be gone the next morning. It was a lie. In fact, he’d be gone before sunrise. In anticipation of this, Mao gave out orders for his men to go to bed early and sleep with their armour and weapons within arm’s reach of their beds.

Sunset fell upon an unsuspecting landscape. The city gates were closed and the day shift of guards went to bed safe in the knowledge that Dongguang was secure while the much smaller night shift took over their posts. All was quiet until unidentified figures appeared from the city. 200 men, all in army-issued lamellar armour, approached the gates from the inside. Confused, the night watchmen asked if the soldiers were there to reinforce the gatehouse. If so, then their presence was unnecessary: nothing was amiss here. Mao Fulong’s men kept the night watchmen talking while they took their positions. Then the officer in charge raised his arm and brought it down in a chopping motion: the soldiers drew their weapons and killed the night watchmen, stormed the gatehouse, killed everyone inside, and finally opened the gate.

Outside, Mao Fulong was waiting with his remaining 300 soldiers and a few hundred magnates’ men. Hearing the fighting inside, they formed up on the opposite side of the bridge, ready to cross. As soon as the gates began to open, they crossed over into the city and began spreading out to seize strategic positions. Although the men at the gatehouse hadn’t managed to sound the alarm, the noise of the fight there alerted nearby sentries, who ran to tell the commander on duty that Dongguang was under attack.

At the same time, the wake-up call was sounded in Mao’s camp, rousing the militia from their slumber, and the order came down to collect their weapons and armour and get ready to move out. Once ready, they were ordered to march into the city. Unlike the soldiers and magnates’ men, the militia hadn’t been informed of what it was they were doing. Some deserted; perhaps foreseeing what was to come, they slipped away into the dark. Most followed orders, marching on into Dongguang in spite of their doubts and fears. Inside the city, Mao Fulong himself stood on a rooftop and addressed them:

“I know you are tired, confused, and perhaps afraid, but you may cast your doubts from your minds. I am Prefect Mao Fulong. I may not have met each one of you, but I know you, and you know me: but who knows this Governor Bai Guguan? The man who sat back as your houses collapsed in the earthquake, who did nothing as your children starved, and watched as the slavers took them away? Do you know that man?”

There was silence for a moment, but Mao asked again: “I said, do you know that man?”

“Yes!” Replied all the militia at once. Mao went on:

“The ruler who neglects and oppresses the people must be removed. Heaven’s verdict is clear: Bai Guguan has no right to govern us! Now it’s up to us to carry out Heaven’s will!”

The speech succeeded at riling up the men, who shouted agreement. Moments later, they were split up and dispersed throughout the city to reinforce the soldiers who’d gone ahead to seize key points all across Dongguang.

A lot of fighting ensued, but it was rather one-sided. The Maomao stormed the other five gatehouses easily. They assaulted the barracks, where the garrison was scrambling to get their weapons and armour, but most were cut down in their night clothes. Most of Bai’s conscripts, along with over half the provincial militia stationed in the city, surrended without a fight. Those who did resist were mostly members of the army, and they were all slaughtered. Only a handful were given the opportunity to surrender.

Meanwhile, Mao’s best men stormed the governor’s palace. Soldiers on duty were few in number and totally unprepared for an attack. Quickly overwhelmed, the guards were all killed and the Maomao entered the compound. Mao himself rushed to the palace after delivering his speech to the militia and entered alongside his men. What happened next is unclear. What is known for sure is that the Maomao helped themselves to the riches of the palace, pocketing silver and other valuables they found—and also helped themselves to the female servants living at the palace. Most impactful on future events, however, is that before the sun rose, Governor Bai Guguan was dead. The manner of his death would soon be a matter of violent controversy: Mao Fulong would maintain until his dying day that Bai was a sickly old man (even though he was only a year older than Mao) and had therefore died of a heart attack when the Maomao broke into his room. Mao’s detractors—especially Bai’s family, none of whom were present in Dongguang at the time—would accuse him of murdering the governor.

6.3 – The Fall of South Province (July 22nd, 1576)

Whatever it was that happened in the governor’s palace that night of July 21st-22nd, the fact was that Mao Fulong was in complete control of Dongguang by the time the sun rose. Of course, the people of Shang, Xia, and Zhou had heard the sounds of battle emanating from Dongguang, but weren’t able to mobilise a response until the morning, at which point the noise had died down. Soldiers and militia reappeared on the city walls, and South Province’s banner continued to fly from the flagpoles, making it look from the outside as if nothing had happened.

But something definitely had happened. Bai Yinzhong, city magistrate of Shang and a distant relation of Bai Guguan, sent men to investigate. Connecting the two cities was a bridge called Dongshang (which is just the first syllable of Dong-guang combined with Shang) Bridge: Bai Yinzhong’s men crossed the Dongshang Bridge and spoke to the guards. Suspiciously, the city gates—which were normally opened at sunrise—were still closed. The guards on the walls told Bai Yinzhong’s men that nothing was amiss, so they should go home. No amount of pestering would get the guards to open the gates, so the men returned to Bai Yinzhong, who was now doubly sure something had gone terribly wrong.

Contingencies were, in fact, already in place in case a situation like this arose. With Dongguang apparently now in unfriendly hands and the governor unaccounted for, Bai Yinzhoung was now in overall command, as magistrate of Shang. As such, Bai Yinzhong sent messengers to call on the magistates of Xia and Zhou, as well the commanders of the fortress-islands of Fort Youkuci, Fort Lasting Vigilance, Fort Vijaya, and Middle Island Fort, summoning them all to a war council at the magistrate’s office in Shang. Although this seemed like the correct decision at the time, it would soon turn out to be a catastrophic mistake.

All the aforementioned officials swiftly boarded ships which took them to Shang, where they met with Bai Yinzhong in his office. Barely an hour passed before a messenger arrived and announced that the Acapulco Expedition had arrived.

As the ships came around the bend in the river, sentries on the walls of Shang spotted them and instantly recognised them. Spanish ships stuck out like a sore thumb in Xinguan waters. Sail design took very different routes in Europe and East Asia, making it obvious to any casual observer that New Spain’s ships weren’t from any Xinguan or Chinese port. And if that wasn’t enough, the ships were proudly flying flags with a white background and a red X running from all four corners to the centre. It was the Cross of Burgundy, easily recognisable to any Xinguan who’d dealt with the Spanish before.

Soon after the ships came in sight, the flags of South Province being flown over Dongguang were lowered and Crosses of Burgundy raised in their stead. While the flags were still being raised, the cannons on Dongguang’s walls opened fire on the magistrate’s office in Shang. It was taller than the city’s curtain wall, which was shorter than Dongguang’s wall, so the gunners had no problem targeting it. Cannonballs crashed though the walls, taking the head off one of the servants and collapsing the front door. A few minutes later, a second volley crashed into the building and most of the roof caved in.

Fortunately for the magistrates inside, they were on the second floor out of three, and the third storey floor held up. When it became clear the building wasn’t safe, they rushed for the exits and made it out before other parts of it started collapsing under the gentle ministrations of Mao’s gunners. Bai Yinzhong, meanwhile, had rushed out of the office as soon as the news of the Mexicans’ arrival had come. Galloping on horseback through the city streets, he climbed up onto the top of the wall in time to see the Mexicans fire their broadsides. Everyone on the wall dove for cover as cannonballs slammed into the crenellations. Only Bai Yinzhong remained standing, apparently unfazed by the cannonade. Shamed by the sight of their leader still on his feet, others quickly got to theirs. Soldiers of Shang manned their own cannons and gave the Mexicans a volley in return.

Boats began launching from the Mexican ships, boats full of Aztecs and Tlaxcallans in befeathered cotton armour wielding macuhuitls and bows alongside Criollos and Spaniards wearing steel cuirasses and helmets with swords and muskets in hand.

Dockworkers, merchants, fishermen, and other civilians who spent their mornings down at the docks were already fleeing in a panic: since the curtain wall didn’t encompass the docks, the civilians all fled for the gates.The first thing Bai Yinzhong did after arrival was order the gates to be shut. A handful of people got in as they were closing, but once they were shut, the rest had to find shelter on their own. Panic-stricken people ran for cover in warehouses, stores, anywhere they could get out of sight of the invaders and hopefully pass underneath their notice. Many ran for the river. Those who could swim made for nearby islands. Those who couldn’t commandeered whatever boats were on hand and pushed off. Some jumped in and willfully sank to the bottom.

For now, however, the civilians had nothing to fear from the Mexicans as long as they didn’t get directly in their way. Te city had to be taken before the looting could begin. Mexicans leapt onto the docks or directly onto the beach and swarmed toward the walls. Some carried ladders: these were rushed to the walls as quickly as possible. Under a hail of arrows and bullets, the ladders were set up and secured to the ground to prevent the defenders pushing them off. Soldiers began swarming up onto the walls, where a fierce melee ensued.

Meanwhile, Dongguang’s northern gate opened and Mao Fulong’s men surged across Dongshang Bridge. On Dongguang’s side, the bridge entered the city through a gate, but on Shang’s side it connected directly to the docks. The Maomao, therefore, had to cross open ground, where they were vulnerable to arrows and bullets from Shang’s defenders, in order to reach the docks’ gate. As they surged through the docks, they passed by the Mexican soldiers. Each Maomao was wearing a red ribbon tied to his arm or a red bandana wrapped around his head to identify him as friendly, so there was no friendly fire incident. Still, both the Maomao and the Mexicans evidently didn’t trust each other too much, as they were careful not to get too close to each other.

When the Maomao closed with the docks gate, a group of them surged ahead of the rest carrying barrels full of gunpowder. Recognising what they were about to do, the defenders hastily refocused fire on them. Meanwhile, the Maomao shot at anything on the wall that moved. A few barrel-carriers were picked off, but the rest delivered their payload. Setting the barrels down, they set a quick fuse and then booked it in the opposite direction. A minute later the barrels exploded, blowing a gaping hole in the gate. Rushing through the breach, the Maomao poured into the streets beyond.

Up on the wall, the defenders saw the enemy was behind them and their spirit broke. They began throwing down their weapons either to surrender or to run away more easily. Hundreds were cut down, hundreds more taken prisoner, and the rest fled for the north gate, which was the nearest way out of Shang. Fortunately the gates were still open, since no one had ordered the guards to close them. Unfortunately, thousands of civilians were already pouring out the north and east gates. Soldiers doffed their armour and did their best to blend in with the crowd.

Meanwhile, Mexicans and the Maomao spread out across the city. Discipline began breaking down: roving gangs of soldiers started looting any valuables they could get their hands on and killing anyone who got in the way. Women were seized as well, and we need not describe in detail what was done to them. Having two different armies who didn’t speak each other’s languages meant friction quickly arose between the Mexicans and the Maomao: there was more than one occasion when both went for the same loot and they decided to resolve their differences with fire and sword.

Mao Fulong watched the proceedings from the wall of Dongguang. He knew the magistrates from the other cities were in Shang because he’d seen their boats passing by. Squads of soldiers from the Danmian garrison, whom Mao had been keeping in reserve until now, were sent into Shang in search of the magistrates of Shang, Xia, and Zhou, as well as the fort commanders.

Bai Yinzhong was killed commanding the defence of the walls. Though not a military man, his presence and unshakeable will had been a stabilising force until the Maomao broke through the gate. Soon afterward, he’d been killed while trying to rally his men.

The commanders of Fort Youkuci and Fort Lasting Vigilance had collected some 20-odd militia and were holding out in a house near the magistrate’s office. Some Zapotec and Yopi warriors tried to storm the building but were repulsed, so they set up a perimeter outside. Mao’s Danmian soldiers arrived a little later and negotiated with the commanders: they would turn themselves in and order the garrisons of the forts they commanded to stand down in exchange for the lives of those same garrisons.

Fort Vijaya’s commander was killed in the streets by looters.

Meanwhile, the magistrates of Xia and Zhou had safely made it out of the city via the east gate. However, the east gate led to Cham Island between Shang and New Vijaya. Besides the bridge to Shang, Cham Island had only one other way off by foot: the bridge to New Vijaya. Cham Island was quickly filling up with refugees from Shang huddled among the trees grown on the island for timber, but New Vijaya’s gates were closed. Xia and Zhou’s magistrates led a gaggle of their secretaries and hangers-on across the bridge and demanded the guards open the gates. They resolutely refused. However, the scene of the island filled with terrified civilians did prompt the guards to call on Prefect Pâl Karutdrak who, for the first time, went up on the wall to see for himself what was going on outside his city.

Excited at the sight of the prefect, the magistrates reiterated their demands to be let in. Aghast at the sight of his island (the border between Miwoke Prefecture and New Champa Prefecture is set on the branch of the river separating Shang from Cham Island) filled with unwanted Chinese townspeople, Pâl Karutdrak was in no mood to be taking demands. In fact, he was incensed at the very idea of these city magistrates from a neighbouring prefecture daring to order him around. With a flourish of his arm, he told them to go away.

Meanwhile, the crowd on the other side of the bridge was getting angrier by the second. When they saw Pâl Karutdrak waving at the magistrates to leave, they were filled with rage. Men charged across the bridge to pound on the gate and yell to be let in. Pâl Karutdrak ordered his men to fire their guns into the river as a warning: this was ignored, so he ordered the men to reload and fire again—into the crowd this time. One volley panicked the crowd as several men fell screaming in pain. Not everyone reacted at once or with the same sense of direction. Those closest to the gates tried to get away, but others who were still behind them were either slow to respond or hadn’t realised what’d happened. Pâl Karutdrak ordered a second volley be fired and more men fell dead or wounded. By now, the people had gotten the message and the bridge rapidly emptied of all except the dead and those too wounded to carry themselves to safety.

Among the dead were the magistrates of Xia and Zhou.

6.4 – Cracks in the Alliance of Convenience (July 23rd – 25th, 1576)

Mao Fulong and Alonso Flores met briefly on the bridge between Shang and Dongguang, but both men had too many things to do to have a lengthy meeting at the time. Instead, they spent the rest of July 22nd consolidating their hold on Shang. In the morning, Mao went around to Middle Island Fort, Fort Lasting Vigilance, Fort Youkuci, and Xia to demand the surrender of each, offering to let the garrison leave with whatever they could carry and to leave the civilians unharmed. One by one, they accepted. Meanwhile, Flores secured the surrender of Zhou and Fort Vijaya.

Once the garrisons of those places vacated the premises, Mao and Flores occupied them. Mao also took this opportunity to release some of his prisoners. Bai Guguan’s press-ganged militia had nearly all surrendered without much of a fight, but Mao had no interest in holding onto them. Dongguang’s southern gate was opened and the prisoners were allowed to return to their homes.

At this point, Mao was still keeping the Dongguang-Shang gate closed and only opened it to those with special written permission signed by Mao himself. He hadn’t given any such permissions to any of Flores’s men. Zhou Xiang—Mao’s secretary—later recorded that Mao’s reasoning for this was that he thought the people of South Province would find it too provocative if he let the Mexicans into the capital city. While this isn’t an entirely insane rationale, it seems more likely his primary reason was that he didn’t fully trust Flores and he wanted to keep a strong base for himself to hold onto in case things went poorly. For his part, Flores may not have trusted Mao much at this point either. Mainly because he had Mei Nai whispering in his ear.

The trip through the Bay from Danmian to Dongguang had been tense, but uneventful. In order to avoid provoking the Northerners, the Mexicans kept to the southern side of the Bay and foraged there. This turned out to be a good idea because northern governor Wei Yonglong had concentrated most of his navy in Ningbo and had scout ships trailing the Mexicans (which the Mexicans spotted and took note of). Had they violated the provincial border, Wei’s fleet would’ve pounced on them. As it was, Wei was content to let them be for the foreseeable future.

On the southern side of the border, there was no effective resistance. Bai Guguan’s fleet patrolling the Red Rock River had finally heard news of the invasion and received Bai’s orders to return, but they were still weeks away.

During the trip, Mei Nai spent almost all her time with Benito Aguilar. She gained his trust by answering his questions about Xinguo and its people and also by teaching him more Yue. In the course of time, she subtly hinted at Mao Fulong’s untrustworthiness in various ways. She spoke of his lack of military talent in being unable to fend off the pirate attack on Danmian in 1554 (but failed to mention this was because of a lack of reinforcements from Dongguang). She talked about how much Coastal Prefecture suffered during the 1573 earthquake and how little Mao had done to address the problem (but failed to point out Mao did all he was able to under the circumstance, even selling his own property for charity). Benito Aguilar shared these tidbits with Flores, so by the time they reached Dongguang they were already primed to believe Mao was less trustworthy and less competent than he wanted them to believe.

By the by, this information comes to us via Juan de Oñate’s memoirs. Oñate claims to have been an unofficial aide de camp to Flores at this point. Whatever the truth of that claim, what Oñate says Mei Nai told Aguilar is accurate to what we know from Xinguan records, except for the fact that Mei Nai was extremely selective with the details so as to paint Mao Fulong in as bad a light as possible.

Her own thoughts on the matter are not recorded, since neither she nor anyone close to her wrote them down for us, but that doesn’t mean they are opaque. We can reasonably surmise that, given her Aztec heritage, she held no love for the Spaniards—the people who’d conquered her home, desecrated her people’s temples, and brought diseases that ravaged them even worse than the diseases the Xinguans had brought in the previous century. Given how hard she worked to convince Flores of Mao’s incompetence and duplicity, and her sons informing Bai Guguan of Mao’s plans, we can safely conclude she was trying to drive a wedge between Flores and Mao and bring the two down. Her motivation for doing so seems clear enough.

Getting back to the situation in Dongguang and Shang, on July 24th Mao and Flores finally had time to schedule a proper meeting. The two men set themselves up in their own city, with Mao in Dongguang and Flores in Shang. Runners carried messages back and forth between them all morning. Mao opened the exchange by inviting Flores to come see him in the governor’s palace. Flores demurred, stating that he’d like to have his own men sharing control of Dongguang before he came over. Mao stalled, saying they could discuss that in person. Flores invited Mao to meet him in Shang. Mao argued that simply wouldn’t do, since the magistrate’s office no longer existed and no other building in Shang was suitable for such an occasion.

Eventually, they agreed to meet in the blockhouse that stood watch over the Shang side of Dongshang Bridge, and that is where they met in the early afternoon of July 24th, together with their interpreters, aides, secretaries, and junior commanders. It was a crowded blockhouse, which added to the sweltering summer heat to make the atmosphere inside almost unbearable.

Nevertheless, the men—and one woman—inside spent hours discussing business. They agreed the Maomao would garrison Fort Lasting Vigilance, Fort Youkuci, Middle Island Fort, and Xia, while Alonso Flores’s men would garrison Zhou and Fort Vijaya. However, things came to a head over the administration of Shang and Dongguang. Once again, we have two conflicting accounts of how the discussion went.

Juan de Oñate writes that Flores opened by offering to let Mao keep his men in Shang as long as Flores could station men in Dongguang, and the two cities would be jointly administered by both Mao and Flores.

Zhou Xiang states Flores flatly demanded joint access to Dongguang and that they could discuss Shang later.

Both record Mao beating around the bush by claiming his men had Dongguang secured and had no need of reinforcements.

They continued to argue past each other for some time like this, with their subordinates occasionally chiming in. Eventually, both our sources record that Mao agreed to a joint administration of Dongguang as long as Mao got to stay in the governor’s palace and his nephew and secretary Zhou Xiang would be returned to him. Flores, in turn, gave up complaining about the presence of Maomao in Shang.

By this time it was late in the day, so the two sides agreed to break it off and continue discussions the next day. This time, they agreed to hold the meeting in the governor’s palace in Dongguang. Mao Fulong returned to the governor’s palace with Zhou Xiang.

At dawn on July 25th, therefore, the gates on Dongshang Bridge were opened. Alonso Flores crossed with his entourage and a few hundred men to begin the join garrisoning of the capital. Once across, however, Flores’s men suddenly whipped out their weapons and held the guards at the gatehouse at gunpoint. Maomao handed over their weapons and were tied up while hundreds more of Flores’s men crossed the bridge. Leaving some of his men behind to secure the gate, Flores marched through the streets with the rest of his men, weapons drawn and musket matches lit, ready for a fight. Mao Fulong didn’t realise what was happening until someone on the second storey spotted the Mexicans marching toward the governor’s palace.

Now, at that time, the governor’s palace stood almost at the centre of the island near where the Palace of Brilliant Purity (Mingqing, a deliberate reference to China’s dynasties of Ming and Qing) stands today. Much smaller than the palace complex occupying the same space today, it was surrounded by its own wall with the main gate facing southward (in accordance with Chinese principles of architecture), but there were smaller gates facing in the other three directions as well. Gathering as many men as he could get with only minutes to spare, Mao posted them around the northern gate and prepared for a siege.

Halting outside rocket arrow range, Flores sent forth Benito Aguilar, Mei Nai, and Juan de Oñate under a white flag. Mao Fulong, terrified a sniper might shoot him if he showed his face, sent Zhou Xiang to negotiate for him. Leaning out a window in the gatehouse, Zhou listened while Aguilar cheerfully bid him good morning in Yue. Given his still quite limited skill in that language, he then switched to Nahuatl, with Mei Nai translating. Aguilar explained that Flores was only here fulfilling their agreement the previous day. Dongguang would be jointly occupied and administered by both armies. In fact, they’d already garrisoned Dongshang Bridge, and were now here merely to jointly occupy the governor’s palace. Zhou said that hadn’t been part of the deal, but Aguilar insisted that it was part of the new deal.

Zhou and Aguilar spent another hour arguing back and forth, with both running back to their respective superiors many times. Finally, Mao Fulong relented. He did not, after all, want a shooting war to start here and now. However, it was at that point, according to Zhou Xiang, that Mao made up his mind. He would be governor, whether it was Bai Guguan standing in his way or Alonso Flores.

The gates were opened and the Mexicans marched in. Flores and his entourage were shown into the governor’s audience chamber, the same room where only days earlier Bai Guguan had been informed of Mao Fulong’s treacherous plans by the Yao brothers. Here, the second meeting began. This time, the main item on the list for discussion was how to proceed with capturing the rest of Xinguo.

Mao told Flores that Bai Guguan had a large family who would most assuredly raise armies to fight them. They would have to die for South Province to be secure. Flores understood this but raised a counterpoint. Having observed the Northern scout ships trailing his own fleet on the way in, he reasoned that the Northerners must have a force of ships and men already prepared. He extrapolated that it would take time for the South to raise new armies, but the North already had a fleet prepared to sweep down onto Dongguang at the first sign of weakness. Therefore, it would be in their mutual best interest to deal a blow to the Northerners first by capturing Ningbo. Once he heard Flores out, Mao agreed. Flores would lead the mission to capture Ningbo with a joint force of Mexicans and Maomao.

All this is recorded more or less the same in both Oñate’s and Zhou’s accounts.

And so the meeting adjourned. Mao remained in the governor’s palace, which was now jointly guarded by both his own men and men loyal to Flores, while Flores returned to Shang to prepare an invasion of North Province.

On the morning of July 25th, a wrench was thrown in all their plans when the Army of Hue arrived, 10,000 strong.

[Next]

Leave a comment