[Xin-Mei Wars V1] [Prev] [Next]

1.1 – Master of Two Provinces (1576 – 1589)

In the year 221 of the Ming Epoch (1589 AD), Lady Ya of the Tao family hung herself in her room during the Siege of Narrow Towers. That same night, the Black Banner Guard broke into the citadel, overrunning the last gasps of resistance, and captured Lady Ya’s husband, self-proclaimed South Province Governor Bai Junli and their son and daughter, Bai Rushi and Bai Xiarong.

Junli was a man of disordered mental capacity. We cannot diagnose the condition of a man who lived centuries ago, but one of his tutors wrote of him that he had “the mind of an eight-year-old” when he was seventeen. Then the tutor quit. Junli’s son Rushi was a man of only nineteen years of age.

Once in custody, the three Bai’s were taken back to Ningbo, capital of North Province. Two weeks later, Junli and Rushi were sentenced to death by a thousand cuts for seizing control of the government. North Province governor Wei Yonglong told them he would be lenient and commuted the sentence to a mere beheading. Both were executed while the fourteen-year-old Bai Xiarong looked on. She requested to spend the rest of her life as a nun, but was turned down. Instead, she was to function as a living legitimacy accessory by marrying Wei Yonglong’s son, Ruzheng. She was given a year to mourn her family. On the morning of the day the wedding was to take place, she was found dead in her room, having slit her wrists.

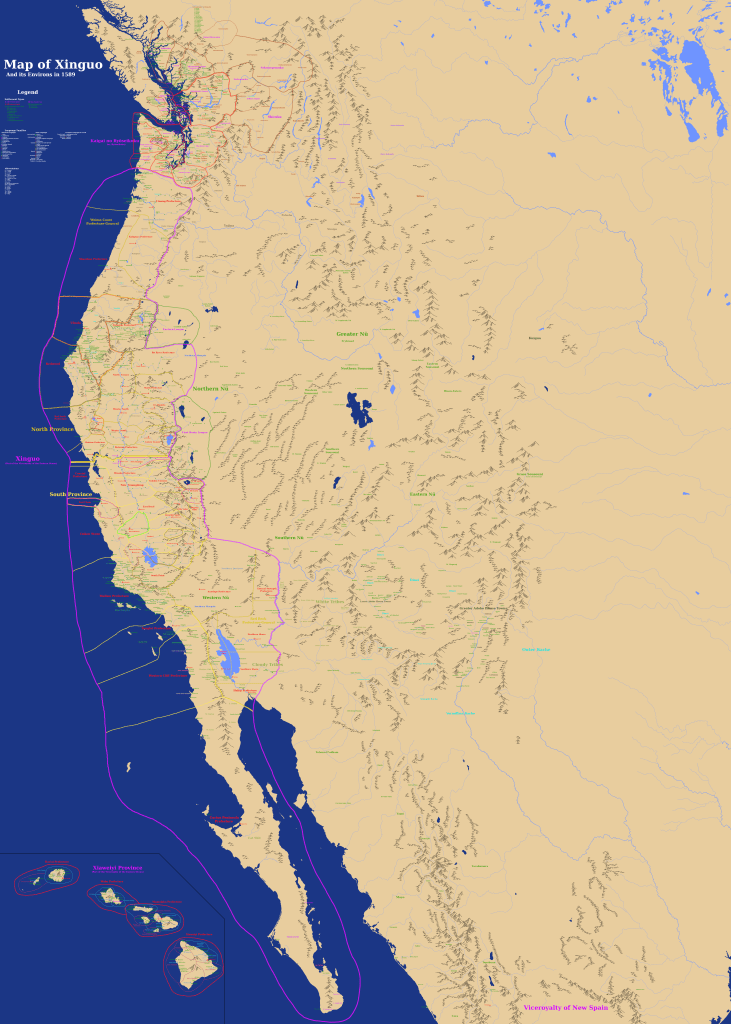

Xiarong’s death was unfortunate for Yonglong, but ultimately it was only a loss in optics. With or without her marriage to his son shoring up his family’s legitimacy, the fact remained that Wei Yonglong was now master of all Xinguo.

All of this stemmed from the events of 1576. That year was discussed in-depth in my previous work, The Xin-Mei Wars Volume 1: Diplomacy and War between Xinguo and Mexico in the 16th Century. I originally intended to go on to Volume 2, but the next conflict between Xinguo and Mexico is to occur in 1680, nearly a century after where we left off in Volume 1. A series of seismic shifts occurred in Xinguo during that century which will need to be understood by the reader before we get to the Pueblo Revolts. To that end, we must briefly return to 1576. We need not go into too much detail here, but I will summarise those events to get the reader up to speed.

Spain and China were at war (the Sino-Spanish War of 1570 – 1577), which meant their colonies, New Spain and Xinguo, were also at war. However, both sides preferred to trade with each other and pretend they were not at war until 1576, when the viceroy of New Spain sent an agent provocateur to Dongguang City, where he blew up a warehouse belonging to Spanish merchants smuggling silver to the Xinguans. The viceroy then mobilised the Acapulco Expedition, which consisted of 36 ships and over 10,000 men. To make a long story short, the expedition was able to seize Dongguang, capital of South Province, but failed to hold onto it. Over the course of a lot of intrigue we need not get into here, the Acapulco Expedition linked up with a rebellious militia army from Coastal Prefecture and withdrew to Danmian, capital of that prefecture. Despite having to withdraw from the provincial capital, the Mexicans and rebels had succeeded in toppling the government of South Province, which soon fell into a multi-sided civil war between three main factions and multiple smaller ones.

Governor Wei Yonglong watched all this with interest. From his position north of the border, he was neutral in the civil war but felt the need to shore up his position. The Northern provincial army garrison was called the Black Banner Guard—named for the plain black banner that served as the flag of the North. Technically, it was a subdivision of the professional military of the Ming Dynasty, but in reality it was an independent military force under the command of Wei Yonglong. To secure his border and his capital (which was only a few miles north of said border), Wei expanded the ranks of the Black Banner Guard.

In addition to the army, Wei had a provincial militia that theoretically consisted of one man in sixteen people in the province. In reality, it was much smaller than this. Large portions of the province were outside the governor’s direct control (a state of affairs we will return to in the next chapter) and a combination of corruption and lethargy at the county level of government meant the provincial militia rolls had a ballooning number of dead or fictitious men on it. Pirates had handed a series of catastrophic defeats to North Province during the Anti-Piracy War (1553 – 1569), but instead of inspiring more men to join the militia out of patriotic duty, the incompetence of the generals had instead inspired men to evade militia service by bribing county officials to strike their names off the lists and replace them with fictitious names or dead relatives. Because this was very profitable for the county officials, bribery had become a booming industry. Besides pirates, North Province faced only hostile Prior tribes, which could be handled by the Black Banner Guard and a relatively small number of militiamen, most of whom lived on the frontier within the area of conflict, which meant the provincial militia didn’t really need to be all that big anyway.

New Spain’s Acapulco Expedition was a wake-up call for Xinguo; a rude reminder that a peer competitor had arrived on the scene, and that competitor was very much capable of putting boots on Xinguan soil.

Wei Yonglong dealt with the provincial militia by blanket-firing most of the county officials, executing some for good measure, and requiring the rest to apply to their local examination offices and re-take the test in order to keep the degrees that enabled them to work in government. He introduced more top-down oversight into the provincial militia recruitment system and offered higher pay for those who signed up.

County officials also received a pay raise in the hopes that it would encourage them to do their jobs without taking bribes. New officials replacing the old ones were ordered to make it their top priority to update the militia rolls. The result was that the provincial militia was effectively rebuilt from scratch.

Another change to the militia came in the form of a new equipment procurement system. Previously, every household was paired with another household. One would provide a man for the militia while the other provided money to pay for his equipment. Wei now required a man from every household, but the government paid for his equipment.

Meanwhile, the Chinese general Qi Jiguang, famous for fighting pirates and Mongols back in Asia, was fired from his job due to court politics and emigrated to Xinguo to make a new life for himself. With his help, the Black Banner Guard was reformed and drilled relentlessly into a formidable fighting force. Qi also demanded they switch out their outdated hand cannons for matchlock muskets. The provincial militia mutinied against his stringent discipline and Qi was removed as their commander, but Wei did order 3,000 matchlocks for the Guard.

In this way, Wei Yonglong built up a combined Guard and militia force of 80,000 braves. It was with this truly massive, well-drilled army that Wei invaded the South in 1587. General Qi Jiguang himself led the invasion. Against this onslaught, the three major factions of the still-ongoing civil war simply stood no chance. All of the South had either been conquered or surrendered to Wei by the end of 1589 (except for the Red Rock river country, which accepted Wei’s suzereinty early the next year).

In order to rule over South Province, Wei Yonglong picked up the next closest male relative of the Bai family, whose name was Bai Ruxun. Ruxun was declared governor of South Province with Wei’s support. He ‘governed’ his province from out of Wei’s palace in Ningbo and was rarely allowed to leave it.

1.2 – War and Tributaries (1553 – 1580)

Paying for all this was expensive, and North Province’s finances were in a bad way. Several measures were taken to raise money. One of the first was to reconsider Ningbo’s relationship with its tributaries.

Ningbo had maintained a network of Prior Nations who paid them tribute ever since its very foundation in 1449. First of these was the Meixiaze, a coastal branch of the Miwoke Nations, which had been the first Priors encountered by Wei Shuifu in 1437. They signed treaties of friendship in 1440 and sent their first tributary embassy to Beijing in 1441. From 1449 onward, they brought their tribute to Ningbo. By the 1570s, the Meixiaze had intermarried with Wu-speaking settlers and integrated with them to the point that they were hardly distinguishable from the settler population except for the fact that they still held onto many old religious and cultural traditions—including the practice of Kuksu, a religion unique to the central portion of the Two Province region (a phrase that includes both the Valley and the adjacent Burning Coast). Even so, people who were officially registered as ‘Meixiaze’ did not pay regular taxes like everybody else (or, at least, not the land tax; they still paid other taxes on goods and services). Instead, they lived in incorporated tribal communities that paid annual tribute to Ningbo and received gifts from the governor in return.

Other Priors who paid tribute to Ningbo included the Northern Miwoke and Northern Youkeqin (both of whom had migrated northward from South Province), the Baduan, Brave, Huozuohao, the Three Nations of New Eel River, the Two Northern Wentu Nations, and many others. All told, it’s hard to keep track of the exact number of tributaries in Ningbo’s network since the number fluctuated over time, and the number is always more than one would think. For example, when we say that the Meixiaze paid tribute to Ningbo, that doesn’t mean that the Meixiaze were treated as a monolithic whole by the tributary system. Instead, the Meixiaze were split up into twelve different tribal communities based on the twelve distinct Meixiaze tribes that existed in precontact times. Each of these had its own independent relationship with Ningbo, paid tribute separately, and are thus counted as twelve individual tributaries on lists kept in the Ningbo Archive. Other nations functioned in a similar way.

There is also the fact that tributary relations were often reconsidered and renegotiated, which resulted in the exact number of tribes with tributary relations fluctuating over time. Tributary relations sometimes began with many villages and even multiple tribes being treated as a single whole. Such conglomerations were routinely split up into smaller communities later on. Other tributaries might lose their tributary status, either because it was cancelled by Ningbo or because they withdrew from the relationship themselves.

Then there is the fact that Xinguan explorers were constantly pushing the limits of mapped territory in America and making contact with new Prior nations. New tributaries were thereby being established all the time. Sometimes, a tributary embassy would arrive from a Prior nation before Ningbo was even aware of its existence. Such was the case with the Shizuhong, a Salishan-speaking nation living on a lake deep in the Rocky Mountains on the eastern edge of the Great Plateau. Explorers from Kaoli City had made contact with the tribe in the 1530s, at which point the traders told the Shizuhong about Ningbo and signed a tributary treaty with them. The Kaoli traders returned home and didn’t bother informing Ningbo about it until after the Shizuhong had arrived in Ningbo with their copy of the treaty in hand.

In the 1560s, North Province was strapped for cash. Governor Wei Yonglong began considering a radical restructuring of the tributary system. This was because of the Anti-Piracy War (1553 – 1569).

Pirates from the Japanese colony of Ryōseikoku, far to the north of Xinguo, had been sponsored as privateers by South Province to raid New Spain during the Silver Wars (1542 – 1552). They’d gained an appetite for the flow of loot that came with pillaging the sotuhern coasts, for after South Province stopped sponsoring them to raid New Spain, they began raiding Xinguo instead. Piractical raids ravaged the coasts and even penetrated deep inland via Xinguo’s extensive canal system. Exorbitant ransoms had to be paid for hostages, fortifications had to be constructed to confine the pirates to the coast, and dreadfully expensive expeditions were sent to hit the pirates’ home bases in Ryōseikoku. More often than not, these expeditions ended in disaster, and even when successful, the success was limited.

In a turn of good fortune, the leader who had united the many smaller pirate gangs was killed in the 2nd Battle of the Jaw in 1569. This created a power vacuum that other warlords scrambled to fill, causing the formerly united pirates to fall into infighting. Now busy fighting each other, the pirates no longer had the resources to launch major raids against Xinguo, which effectively ended the war.

All was not good for Xinguo, however. The same day the 2nd Battle of the Jaw ended, news arrived that a new war had begun in the Pit River country.

East of the northern tip of the Valley lay a heavily forested region called the Pit River country, which was named for the Pit Trappers. They, in turn, were named for their favourite method of hunting, which involved digging pits in the ground and camouflaging them so deer would fall in and get stuck, whereupon they could easily be dispatched. The Pit Trappers had become tributaries back in the 1470s and had generally maintained good relations with Ningbo. Daily interaction between the Pit Trappers and Xinguo was mediated by the Pit River Merchant Society, whose main trading post was a small fort called Bright Valuables, which lay beyond the frontier deep in Pit River territory.

In the 1560s, Ningbo had steadily begun demanding higher amounts of tribute while giving fewer gifts in return. Meanwhile, higher taxes on merchant goods prompted the Pit River Merchant Society to raise its prices. Finally, in 1569, the Pit Trappers could take no more. 400 braves armed themselves with weapons sold to them by the Pit River Society and attacked Bright Valuables. Company employees were all massacred except one, and the post was burned to the ground. The lone survivor was sent home to tell the story.

This kicked off the Pit River War, which was to rage on until 1582. Almost every year, an expedition of 1,000-2,000 men was sent to pacify the Pit Trappers, but it turned out that their pit traps were just as good at trapping men as deer. Spikes were added to the bottom of the pit. Poison was applied to the spike, most often by simply defecating on them. Other spike traps were employed as well. Trip wires were strung across forest paths that would release tension-traps that would slap the offender in the face. Another favourite was to suspend rocks or logs high in the canopy and hidden by camouflage. At the release of a trip wire, rocks and logs would rain down on the offender. Those were the complex traps, but simple traps were utilised as well. A foot-sized, ankle-deep pit line with spikes could very lock a trespasser in place, presenting a still target for a sniper to finish off. Or it could simply poison him and take him out of action that way. A single spike strike out and jab a trespasser with poison, or a hidden rope with a specialised knot might catch his ankle and hold him in place right before an ambush.

Trap fields of this kind were set up overnight in the path of invading armies. Xinguan soldiers would go down to a stream for water in the evening and then go to the same spot again in the morning and fall in a trap on the way. Armies that turned to go home would find trap fields had been set up behind them. Xinguan braves who were foolish enough to go anywhere alone or in groups of less than five would not be seen again—not alive, anyway. In this way, twelve expeditions were sent home with their tails between their legs. One expedition spent the whole summer of 1572 in the Pit River country and lost 200 braves dead or missing without ever engaging the enemy or finding any of their villages. Meanwhile, Pit Trapper raiding parties crossed into Xinguan territory and sowed terror all along the frontier.

In the end, it was not Xinguan military might that laid the Pit Trappers low, but typhoid. In 1580-1581, a typoid epidemic ravaged the Two Pit Trapper Nations and killed huge numbers of braves. In the meantime, the Xinguans had developed more effective methods of avoiding or countering traps and ambushes. Two final expeditions in 1581 and ’82 succeeded in razing dozens of Pit Trapper villages and killing or enslaving hundreds of people. The Pit Trappers were finally forced to surrender most of their land and were restricted to a small reservation in Southern Pit Trapper territory.

It’s said that the sinews of war are infinite money, and leaders throughout history have sought ways to make wars pay for themselves (mainly by waging the war in enemy territory and stealing anything that fits into the broadest possible definition of ‘portable’). However, the Anti-Piracy and Pit River wars were that deadly combination of extremely expensive with few opportunities to make the war pay for itself. By the 1570s, North Province’s finances were in a bad way.

To rectify this, Wei Yonglong started cutting corners. Forts built during the Anti-Piracy War were stripped down to skeleton crews, the weapons and supplies inside sold to private buyers or sent north to equip yet another Pit River expedition. And so we return to what I pointed out at the beginning of this section; one of the first means of cutting expenditure was to cut back on the gifts given to tributaries. As we saw with the Pit Trappers, this could backfire spectacularly.

Another uprising was sparked in Yiwuxian Prefecture, where the Two Magala Nations had signed tributary treaties with North Province in the 1490s. Wei Yonglong stopped giving them gifts in return for tribute in 1570. The stopped paying tribute, which prompted Wei Yonglong to send in the Black Banner Guard to seize tribute by force in 1575, and that elicited retaliatory raids that sparked the Magala Uprising. That, however, is a story that will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter, where we will discuss the history of Yiwuxian Prefecture. Long story short, Wei Yonglong left Yiwuxian to handle the uprising on its own so that he didn’t have to pay for the the war.

There was one more method by which Wei Yonglong could cut tributary costs. Because ceasing return gifts had gone so well with the Pit Trappers and Magala, Wei Yonglong decided to revoke tributary status entirely from several other groups, namely from the Cheon Dul in Ulnala Prefecture, from the Minwei in Redwood, and from the Meixiaze in Meixiaze Prefecture. All of these groups were of mixed racial origins, with both Prior and Chinese heritage (except the Cheon Dul, who were a Prior and Korean mix). All of them had largely assimilated into settler culture and were considered by Ningbo to be indistinguishable from the settlers among whom they lived. Thus, Wei Yonglong reasoned, they were not Priors and should not enjoy the privileged status of tributaries. Recognition as Prior nations was revoked from these groups in 1578, and with that, their status as tributaries was ended. Instead of paying tribute, they would now have to pay the land tax just like everyone else. More than that, they lost the right to maintain their own autonomous tribal governments and all considerations given for their distinct religious and cultural heritage were thrown out the window.

A broad net had been cast, and other Priors were caught up in it as well. In 1579, the Keyongkewangma and Nisennan lost recognition, and in 1580 the Kekewaka and Laxike did too. The Red Earth, Great and Little Wukou, Huqin, Huozuohao, and Brave lost status in the ensuing years.

All this sparked a great deal of outrage, riots, and a string of violent uprisings, especially among the Cheon Dul and Minwei. Unlike the Pit Trappers and Magala, however, none of these groups lived in frontier areas. They lived in highly developed areas, some of them in the very heart of Xinguo itself, all of them living among or very close to Xinguan settler communities. Uprisings were swiftly crushed at minimal cost and the ensuing legal battles to regain Prior status all failed.

Meanwhile, Wei Yonglong increased taxes on the autonomous prefectures of Ulnala and Redwood. Being separated from the Valley by distance and mountains, they had long governed themselves with little interference from Ningbo. Wei Yonglong was able to convince them to accept the tax hike, however, because the revocation of Cheon Dul and Minwei Prior status meant that the prefectural governments could now tax them as well, and so would actually be gaining more revenue than before despite the tax hike.

In addition to the increased tax revenue, when the Magala Uprising and Pit River War were finally over in 1580 and 1582 respectively, the provincial government was able to seize vast tracts of land from them and sell it off to private buyers, which injected a much-needed influx of cash into the government’s coffers. In the coming years, new people would settle on the land and turn into profitable farms and booming frontier towns that would provide a more stable, long-term source of revenue.

1.3 – A History of Printing in Xinguo (1453 – 1580)

Another method Governor Wei Yonglong increased the provincial government’s bank balance was one that had been used by governments for millennia in times of financial difficulty. If, after all, one cannot increase the size of the economy, why not increase the government’s share of the available resources by increasing the size of the currency supply itself?

Now, one might imagine that Xinguans used silver and copper coinage as currency, since that’s what was used in China. However, China went through phases of eschewing hard cash in favour of paper currency. One such phase was in the 15th century, when the Ming government kept trying to hoard silver for its own purposes while foisting fiat paper currency on the general population, who very much preferred hard cash in the form of precious metals. By the end of the 15th century, enough silver was flowing in from Japan and Xinguo, as well as China’s own silver mines, that silver coinage became more standard.

However, this just exported the problem to Xinguo. Silver was far too valuable as an export to China for the government to allow it to be used as common currency in Xinguo. Copper coinage was used occasionally, but mainly the currency of choice was paper. And for paper currency, one needed printing.

China possessed printing technology centuries before Europe. Printing was invented in China in the 7th century, during the Tang Dynasty. Type could be made from various materials, but by the 16th century it was usually either woodblock or metal moveable type (metal type itself had been invented in Korea).

Woodblock printing worked by carving an image or text into a flat, wooden surface. The surface was then inked, while the carved-out portions acted as the background. The woodblock was then pressed onto fabric or paper, transferring the ink onto the material in the pattern determined by the carving. Woodblocks could be used for printing images or text, but since it was made of a single piece of carved wood, it could only be used to print an entire page of text at a time. The advantage of this was that, if only a single page of text was needed, it was easy to quickly carve out a block and print many copies of that one page. The disadvantage was that woodblocks wore out quickly because the process of repeatedly being wet and then dried out would eventually warp the wood so that the carving was no longer flat enough to transfer the ink correctly.

Moveable type printing worked in much the same way, the difference being that a block of moveable type was made up of a number of smaller blocks fastened together, with each block being cast in the shape of a single written character (such an A or a B, or in China’s case a 乙). Moveable type was, therefore, strictly for printing text. Its advantage was that it could be arranged to print 100 copies of one page of a book, then rearranged to print 100 copies of the next page, and so on. It was also far more durable than woodblocks.

Printing was brought to Xinguo by Islamic missionaries in 1453, and the first extant printed document is an Islamic missionary tract printed in September of that year. It is written in both Chinese and in a script that uses Chinese characters to transcribe the Maliwo language (which is one of the Toumoluo languages). Although the tract itself doesn’t have a date on it, we know when it was printed because in October, 1453, a gazetteer was printed for the town of Maliwo that records the progress of missionary work in the region and gives a date for the tracts that were being printed. Copies of this gazetteer were then transported across the Pacific and delivered to financial backers in China as a sort of proto-newsletter.

Gazetteers have a long history in China. English grammar suggests that the word gazetteer would refer to a person who runs a gazette (which is a newspaper), but for some strange reason hidden in the arcane annals of eldritch etymological history, that isn’t the case. Instead, a gazetteer is a geographical dictionary or index often used as a companion to an atlas or a map. In the Chinese context, gazetteers record all kinds of local lore including geography, statistics, local customs, biographies of famous people born in the area, etc. Gazetteers operated at the grass-roots level, being written for and printed by local people and mainly consumed at the local level. During the Ming Dynasty, gazetteers became so popular that almost every county had one. For a county to lack a gazetteer was incredibly gauche, and one could be certain that it was a place where nothing interesting ever happened.

After 1453, printing quickly spread throughout Xinguo and gazetteers became an intercontinental sensation. Sometimes, a gazetteer was confined to a specific area, but often it was specific to a person who travelled around writing about whatever he or she saw and experienced. People in Xinguo wrote out their gazetteers by hand, printed off a few hundred or thousand copies, and sold them to merchants who brought them back to China and sold them at a mark-up. Chinese readers loved reading first-hand or second-hand accounts of what life was like in Xinguo. Tales of derring-do competed for space with stories of war, interracial love, treaties signed and broken, and exploration expeditions. For those with a love of romance, there was no shortage of love stories. Those with a sense of adventure could sink their teeth into stories of exploration and first contact with foreign peoples. Readers who enjoyed learning about other cultures, languages, and religions had diverse accounts of the customs of an endless parade of Prior peoples. There were even accounts about the Spanish-Aztec and Spanish-Inca wars from the perspective of Xinguan travellers present at the time, not to mention tales from the Silver Wars, Anti-Piracy War, the Warehouse War, and various frontier conflicts.

From China, Xinguan gazetteers spread out to Korea, Japan, the Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam, the Philippines, and even to Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Some of them were even written in Vietnamese, Korean, or Tagalog. The spread and popularity of gazetteers is a major part of how awareness about America spread throughout East and Southeast Asia, which brought migrants from so many diverse places to Xinguo.

But, to get back to paper currency, the first batch of money was printed in Ningbo in 1462. Authentication was required to prove that the money was actually issued by the government, and this was provided by a seal stamped in the centre of the money note. Seals could not be produced in Xinguo, however. Not legally, anyway. They had to be made in China and sent over on the Treasure Fleet. It was one of the few levers China used to influence Xinguo when they felt the need to do so. Seals, therefore, could not be produced on demand, and China only sent a limited number of them, which limited the speed at which new currency could be issued, since each and every note had to be stamped.

And yet, somehow, Governor Wei Yonglong was able to print off thousands of new notes in record time in the 1570s whenever he was desperate for cash to pay for another Pit River expedition. Most likely, he had illegal copies of the imperial seal made at some point, but of course no official record of such a thing exists. Suddenly spiking the volume of currency in circulation was damaging to the economy in the long-term, but it was actually very good for the government in the short-term. Since the government was the one issuing the notes, the government could increase its own share of the currency in circulation by fiat by simply printing more. This was obviously unpopular, since it naturally decreased the real purchasing power of everyone else, but it helped pay the government’s bills.

1.4 – Resuscitating the Economy of a United Xinguo (1589 – 1591)

Inflation became a serious problem by the early 1580s. This was the point at which the Magala and Pit River wars ended, which enabled Wei Yonglong to seize vast tracts of land from the defeated enemies and sell it, which staved off the need for inflationary printing for a while.

However, the conquest of South Province in the 1587 – 1589 Two Provinces War brought another problem into play. The eleven-year civil war in the South had come with its own economic woes. Each of the three main factions vying for power had been printing its own currency, each one using its own illegal seal to stamp the notes with. Any time they captured a new area from one of their rivals, they would force their rival’s currency out of circulation (often by burning it or ordering it to be used as toilet paper) and new currency of their own was printed to replace it. When the enemy advanced, they would take as much of their money as they could with them as they retreated so it would fall into enemy hands, then print money again when they advanced. Every time they needed to recruit more soldiers, build a new fort or refurbish an old one, or purchase a batch of weapons, the rival governors printed more money. Merchants didn’t like taking the governors’ currency for their goods; with so much of it floating around, it was all but worthless and what little worth it did ave was tied to battlefield success. Loss in territory result in a dip in the value of that faction’s currency as people lost confidence in it. And, as previously stated, the government would seize all currency found in their territory that belonged to one of the other factions.

All of this made for an atrocious mess that Wei Yonglong inherited by conquering the South. During the civil war in the South, trade between North and South had been relatively limited. Currency from the South filtered through to the North, but only in small quantities. Once the provinces were united, worthless counterfeit currency flooded the North. Wei dealt with the problem by producing an entirely new seal; not a an illegal copy of the Ming imperial seal, mind you, but an entirely new seal of his own design. Produced in 1590, these seals were used to stamp a new issue of government notes that replaced all previous currencies over the course of the next few years. This issue of new currency also enabled Wei to repair some of the damage done by his inflationary printing in the 1570s, since the new notes replaced the old ones at a ratio of about 1:3, thereby cutting the currency volume down by two-thirds.

In the following year, 1591, Wei Yonglong died of natural causes. His son, Wei Ruzheng, succeeded him. Wei Ruzheng inherited the title Duke of Jia, which the Wei’s had held since it was conferred upon Wei Shuifu for discovering America. He also called himself governor, but since he never went to China to have the title confirmed by the emperor, he was never officially confirmed. But that didn’t bother him any. Well, it did, as a string of revolts broke out during his reign, but all of them were handily crushed by the Black Banner Guard and the provincial militia.

Meanwhile, Bai Ruxun—the man Wei Yonglong used as a puppet governor for the south—disappears from the historical record sometime in the 1590s. Perhaps he died of natural causes. It’s unclear, but no one cared about him by that point and Wei Ruzheng didn’t bother appointing a successor. He was happy to rule as master of two provinces.

However, there were still some internal problems in Wei Ruzheng’s own home territory. Everything north of the Bay to the end of the earth fell within North Province’s claim to America. In practice, however, North Province was divided into five regions. First and largest of these was the Valley and the adjacent coast (called the Burning Coast), which Wei governed directly. The four other regions were Redwood Prefecture, Ulnala Prefecture (called Ao’er in Mandarin), Yiwuxian Prefecture, and the Weima Coast, which consisted of the prefectures of Cinong, Kalapuya, and Shaoshao. Each of these was governed by local strongmen who were given official government positions by Ningbo, but who relied on their own power bases independent of the capital. If they wanted, they could simply ignore orders given to them by the governor.

To keep them in line, he had to make it worth their while to work with him. This was done mainly by letting them do business with the rest of Xinguo and by sharing with them the emperor’s gifts brought back by the Treasure Fleet every year.

Since I’ve neglected to discuss these regions in this series so far, we are going to take a lengthy detour into North Province’s so-called ‘Outer Prefectures’ before returning to the main narrative.

[Next]

Leave a comment