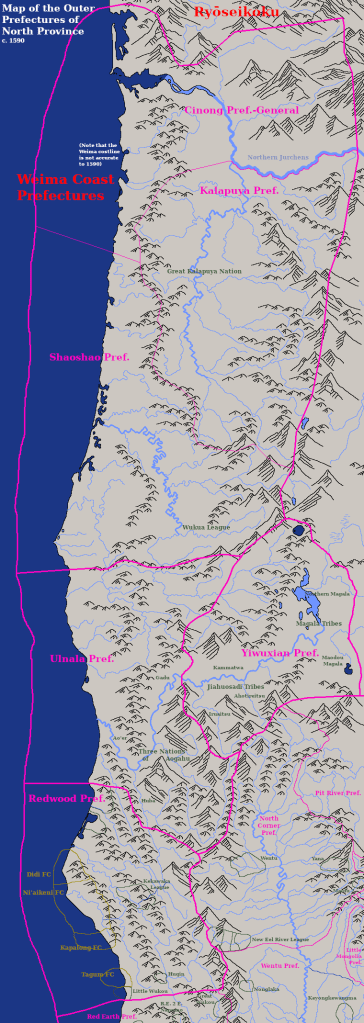

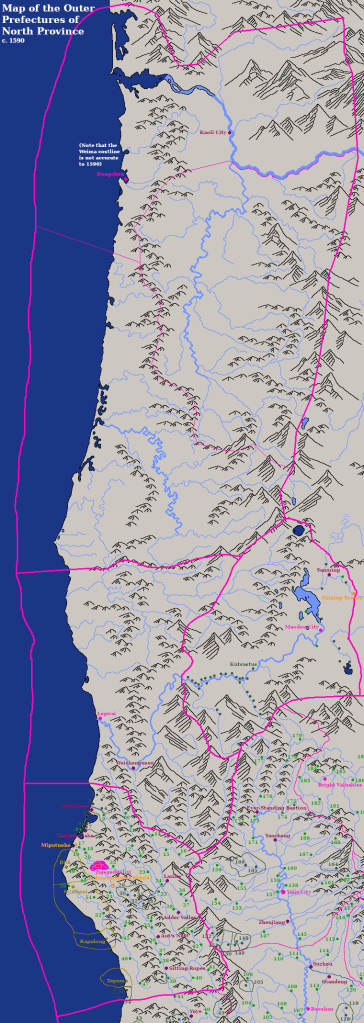

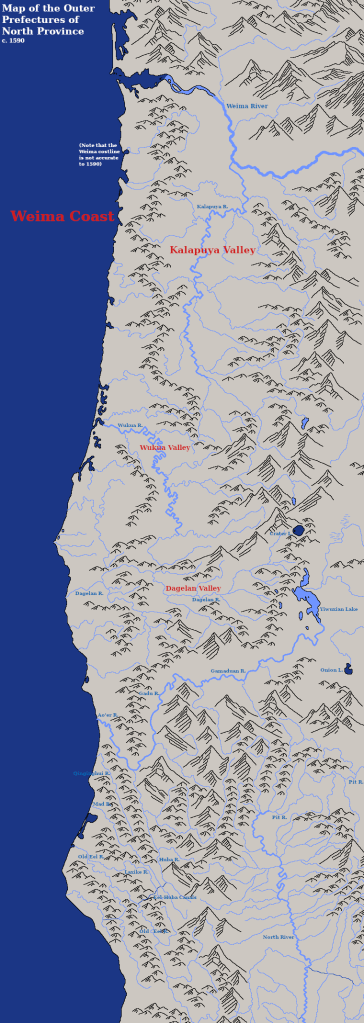

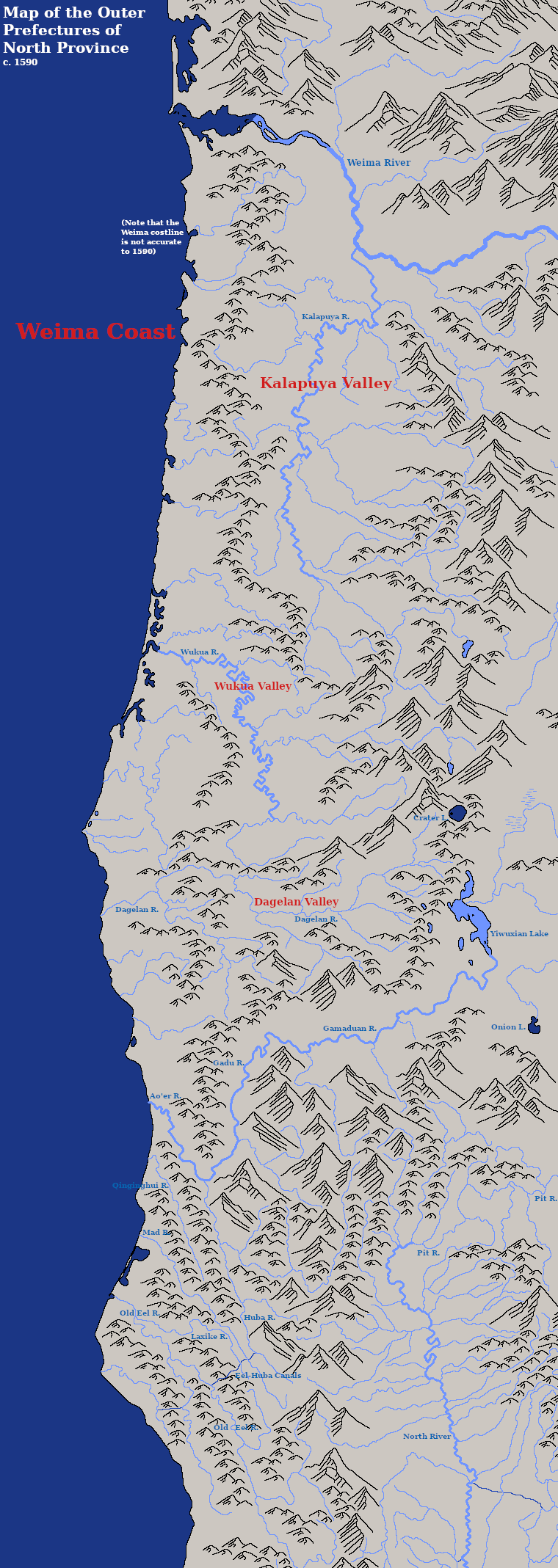

A preview of a new map I’m working on for Xinguo. This part of the map is still very incomplete… will update later.

2.1 – A Survey of Redwood (1437 – 1589)

To take it from the top, Redwood Prefecture was an area inhabited primarily by Min-speaking Chinese settlers from Fujian Province. Despite being on the coast, most of Fujian is covered in rugged mountainous terrain, making it hard for the central government to exert control over until modern times, which gave the inhabitants a sense of autonomy from the rest of China. In addition, Min is a highly divergent set of dialects compared to other varieties of Chinese. It split from the rest of Chinese much earlier than the division that gave rise to Mandarin, Wu, and Yue. Min isn’t a single language or dialect, but rather a whole group of them, more like a mini-language family in its own right rather than anything resembling a unified whole. Several dialects aren’t even intelligible to each other. In Xinguo, however, people from different parts of Fujian mingled together to the degree that they all ended up learning the Hokkien dialect, which became more less the only dialect spoken by any large numbers of people in Redwood Prefecture.

Besides the Min-speakers, there were smaller numbers of Cham, Vietnamese, and Filipino immigrants who also settled in Redwood.

Long before any Asian set foot in Redwood, however, there were the Prior nations. Namely, there were the Weiyue, the Eel River tribes, and the Wukou-Huqin peoples. Each of these three groups traditionally spoke languages belonging to different families and are divisible into multiple smaller groups. For the Weiyue, there were the Wiyat, Wiki, and Patawat. All three are usually given in their native-language form because the Chinese normally just called them all Weiyue.

Of the Eel River tribes, there were nine: Qiuliuliao, Huigui, and Nongjiate, who all lived in the Bald Hills, then the Laxike and Jinisi who actually lived on the Eel River itself and neighbouring streams, and finally on the coast there were the Didi, Ni’aikeni, Xinjin, and Katou. A tenth tribe called the Kekawaka emerged in the 15th century out of an association of Jinisi and Laxike villages along one of the tributaries of the Eel River, who mingled with the Min settlers, intermarried, and exchanged cultural ideas. The Kekewaka allied with the Min and aided them in their wars against the other Eel River tribes.

South of the Eel River tribes (although still partially on the Eel River itself) were the Wukou-Huqin peoples, comprised of the Great Wukou, Huqin, and Little Wukou, all three of which had smaller divisions within themselves.

There was no political coordination between these groups, and very little formal organisation within them. In essence, every little village was its own independent nation. Smaller villages did tend to be economically and socially dependent on larger villages nearby, which resulted in a political smorgasbord of larger towns acting as tribal units in their own right while satellite villages tended to follow their lead.

Political organisation on a larger scale was not needed. The rivers were full of fish and the forests overflowing with berries, tubers, acorns, and game animals. Abundance came naturally in this region, but even so the people maximised the forest’s output with controlled fires to encourage the growth of the most desireable food and medicinal plants and to encourage the proliferation of game animals. Food was, therefore, available in abundance. Violent conflict was rarely necessary and when it did break out, it was localised in small areas and fought between no more than a hundred armed men on both sides combined.

Chinese settlers who first began living in the area settled among the Weiyue in the 1440s. In the beginning, they came only to trade and establish outposts for exploiting the bounties of the sea—especially fur-bearing sea mammals such as the otter. Soon, more settlers arrived and began farming. They intermingled with the Weiyue, signing agreements with them, trading knowledge and cultural practices, and intermarrying. A steady influx of new settlers pushed the frontier beyond the Weiyue’s borders and started settling in the lands of the Eel River tribes.

In order to oversee the business of trade and otter-hunting, as well as to exert control of the frontier, then-governor Wei Dongshi established Redwood Prefecture in 1473. The Wiyat border village of Kigegodolihi was selected as the prefectural capital and was named, in Mandarin, Jigegeduolixi, or Jige for short. Over time, the Weiyue and Chinese settlers melded into one population called the Minwei, from a combination of Min and Weiyue. The Weiyue people ceased to exist, not by massacre, but by cultural assimilation. Weiyue language died out and their culture was mostly abandoned even as the very sites of their villages transformed into Chinese settlements. Old Weiyue place names were retained, but were adapted to Chinese. Today, there are no more full-blooded Weiyue people left.

That being said, elements of their culture and religion remain embedded within the local culture of the area the Weiyue inhabited and have diffused, to some extent, throughout Redwood. Some of the ancient dances and festivals are still held today, albeit in an altered form. There are Minwei people today who have organised and are trying to revive Weiyue language and traditions.

As Jige City grew and more of the region was settled by Min and other Asians, politics in Redwood Prefecture came to be dominated by a group of magnates and business tycoons who came from a range of cultural backgrounds with diverse interests that made for a competitive environment in which no single individual or family was able to win clear dominance over the others. In 1473, Redwood Prefecture was created with its seat at Jigegeduolixi. However, the prefect had very little influence outside the immediate environs of his capital.

Things changed in 1474, when the settler-communities of Didi City and Ni’aikeni City crossed a red line set by their namesakes, Didi Tribe and Ni’aikeni Tribe. Having signed treaties with the cities in the 1460s, the tribes hoped the settlers would stay on their side of he agreed-upon border. Instead, the tribes were used as a source of cheap labour by farmers, fishermen, and otter hunters. Often, the tribesmen were taken far from home without their consent and sometimes the tribesmen were nowhere to be seen when the ships returned. Settlers were also encroaching on tribal lands and, worst of all, unscrupulous members of the settler communities were conning tribespeople into selling their children into slavery—or were straight up kidnapping children to sell. To put a stop to all this, the tribes formed the Bear River Confederacy and attacked the two settler-communities.

The war went poorly for Didi and Ni’aikeni Cities, who had to withdraw back to their side of the border, which resulted in the conflict going dormant. To prevent such a thing from ocurring in the future, the two cities appealed to Jige for help. Jige saw in this as a golden opportunity. The prefect went to all the magnates and major business owners in the area and formed a council for mutual cooperation on matters of defence and expansion called the Jifangmeng (Jífángméng – 吉防盟: Auspicious Defence Covenant, with Jí/吉 being short for Jigegeduolixi).

After the Redwood Wars came to an end at the Blue Earth Great Peace Confederence in 1513, the Jifangmeng lost its purpose. Presided over by the prefect and attended mainly by militia leaders and Black Banner Guard officers, it no longer had any large-scale wars to fight, and so it atrophied. However, the spirit of the Covenant lived on in a new organisation. The elite families of Redwood had taken notice that having a forum for discussion and mutual cooperation helped minimise conflicts between them, resolve feuds that did arise, and maximised all their chances of achieving their disparate goals. Therefore, in 1515, the elites founded the Jige Society for Harmony and Good Advice, or JSHGA. A more popular name for it was the Oligarchy (Guǎzhì – 寡治, few govern, or few regulate).

Its members were the following:

- The Guo family, who were Min-speaking magnates from the area around Jige City. Other rural Min settlers tended to align with the Guo in pursuit of their own interests.

- The Liao family, another Min-speaking magnate family from the Habeila’ao area. Through intermarriage with the chiefs of that town, they inherited land there and bought most of the rest, eventually becoming chiefs themselves.

- The Du family, Min-speakers who dominated the Qialuokejiake Fur Society, which hunted and traded for furs all the way up the coast to Ryōseikoku. They dominated commerce in Redwood’s urban centres.

- The Teng family, who spoke Min and had adopted a Chinese name, but were in fact descended from a long line of wealthy Weiyue chiefs from Huowoqijixi, which had grown into one of the biggest Weiyue towns in the early contact period. As the most powerful of all the ancient Weiyue families, the Teng were looked to for leadership by Weiyue and Minwei alike.

- The Không family, magnates from the Vietnamese colony of Didi.

- The Kosem family, magnates from the Cham colony of Ni’aikeni.

- The Kanoy family, magnates from the Dongdu colony of Kapalong (‘Kanoy’ is here spelled with a ‘K’ as per Xinguo-Dongdu spelling conventions; the same name would be spelled ‘Canoy’ in the Philippines).

- The Paglinawan family, who owned sea mammal and whale hunting business that formed the economic backbone of the Dongdu colony of Tagum.

- The Kekewaka Society Council, who were a delegation of chiefs chosen by the Kekewaka to represent their interests in Jige City. Unlike others in the Oligarchy, the Kekawaka Society was not a family, but were merely delegates chosen to represent their respective communities. Membership shifted over time as old chiefs retired and new ones were selected, but there was always one from each of the five largest Kekewaka communities of North Town, Blue Earth, Arrow Town, Bow Town, and Red Pestle.

The Oligarchy was avowedly not a government agency; they insisted that they were merely a forum of discussion between Redwood’s major interest groups who would also advise the government on matters of importance to the people of the prefecture. In practice, everyone knew the Oligarchs were the true masters of Redwood. The Oligarchy would write letters of recommendation to Ningbo as to who should be appointed as prefect (or when they thought an incumbent prefect should be removed), and Ningbo normally complied. Recommendations were also made to the prefect himself as to who should fill local offices.

To keep hold of their power, the Oligarchy pressured the prefects into passing laws that regulated the market to prevent any upstart businesses from being able to compete with those owned by the Oligarchs (the Oligarchs themselves were, naturally, able to obtain exemptions to the regulations). Land ownership was tightly regulated as well, enabling the Oligarchs and their families to retain ownership of around 70% of the land in the prefecture, including almost all of the land ceded by the Eel River Confederacy in the Great Peace Conference of 1515. Much of the rural population was reduced to the level of tenant farmers and clients who were dependent on staying in the Oligarchs’ good graces or risk beng made landless and homeless.

Among those rural people living in grinding poverty were the surviving members of the Eel River tribes. During the Redwood Wars, they’d been weakened by hunger and suffered diseases spread by settlers poisoning their water sources and were subjected to multiple massacres both during both war and even in peacetime. Having been forced to give up most of their land in the conference, they were reduced to grinding poverty and had to work for the same people who had massacred them just a few years prior.

To escape the poverty trap, most of the Eel River people migrated into the Valley in the 1530s, where land was more plentiful. Then-governor Wei Chengjia granted them land along a stream that became known as New Eel River, where their descendants remain to this day and are officially recognised as the Eel River League. In exchange for the land grant by Wei Chengjia, the Eel River people had to serve in the Black Banner Guard as scouts. The Eel River Scout Battalion fought in the Pit River War, the Two Provinces War, the War of the Matches, the civil wars of the Imperial Era, and many other conflicts besides.

Meanwhile, some Eel River people remained in Redwood. In the late 20th century, they finally gained official recognition as the League of Old Eel River.

As regards the Oligarchy’s relationship with the rest of Xinguo, the Oligarchs always supported the Wei family as governors of North Province as long as the Weis stayed out of their business. For example, they hid Wei Chengjia when he was deposed by Lin Weishi in 1548 and helped him return to power in 1550.

When Wei Yonglong became master of Two Provinces, the Oligarchy continued to support him and even paid his increased taxes on time and in full. He, in turn, left them to run their prefecture as they saw fit and always followed their recommendations on who should hold the office of prefect.

2.2 – A Survey of Ulnala (1437 – 1589)

Ulnala is the region northeast of Redwood, traditionally inhabited by the Ao’er, Gadu, and Huba peoples, among others. Over time, Ulnala grew to include areas to the north, east, and south of this core. The name comes from Oohl, which means ‘The people’ and is the Ao’er’s name for themselves. Koreans who settled in the area in the 15th century pronounced this as Ul, and added ‘nala’ (land) to it. In Mandarin, Oohl is variously written as either Wu’er or Ao’er.

In precolonial times, the Ao’er, Gadu, and Huba peoples formed the southern spur of a great civilisation that stretched along the coastal plains all the way up into Alasaka, generally known in English as the Pacific Northwest. Although the Ao’er, Gadu, and Huba spoke unrelated languages, their precontant cultures were so similar that early settlers couldn’t tell them apart. Today, they are collectively referred to as the Three Nations of Aogahu, although this name has come under fire due to its neglect of the oft-overlooked Qinginghui, who were closely related to (but distinct from) the Huba.

Standing at the crossroads of other Pacific Northwest peoples and the cultures of the Valley and its adjacent coasts, the Aogahu possess elements of both cultural complexes. Like the Valley peoples, Aogahu women traditionally wore tattooes that indicated tribal affiliation and both women and men dressed in a skirt and little else, going barefoot and topless whenever the weather permitted. More similar to their northern neighbours, however, they had a well-developed sense of private property. Fishing spots, hunting grounds, and acorn tracts were all owned privately. Houses were owned and passed down by individuals. Even magic spells were private property.

Every crime, injury, and wrongdoing was considered as an offence by one man against another man. Crimes were resolved by the paying of a fine by the guilty to the injured party. Every fine had to be individually calculated based on the wealth and social standing of the injured party. A crime against a woman was functionally a crime against her husband or male relative. Since she was generally unable to represent herself in any legal proceedings, the crime would go uncompensated unless a male relative took up her case.

In short, it was a hierarchical, patriarchal, wealth-based society.

Koreans were the primary Asian group to settle in the region. Settlement was carried out under Chinese auspices, however, so the colony was a dependency of Xinguo from its inception. Even so, it had a high degree of autonomy from the beginning and always maintained ties with Korea.

Instead of outright conquest and subjugation, Korean whalers and otter-hunters began purchasing unused tracts of land in Ulnala in the 1450s, intermarried with the locals, and lived alongside them. They taught locals how to farm and sold them barnyard animals. Asian diseases spread and devastated the indigenous population as it did everywhere else, and this enabled the settlers to buy up even more land since the owners no longer had the manpower to make use of it.

Wars were not unknown, however. Feuding had always been a fact of life in Ulnala, but the settlers changed everything. New weapons and tactics changed the face of warfare forever. Political organisation on a higher level and with greater detail even at the lower levels enabled wars to be fought on a much grander scale. Battles had once taken place between a few dozen individuals on each side, with every death to be individually compensated for in the peace treaty so that the formerly warring sides could be reconciled after the bloodshed. Now, battles involved hundreds or even thousands of people. Peace was made by extracting terms of surrender from the vanquished, and debts incurred by deaths inflicted went unpaid.

In 1473, the same decreee that created Redwood Prefecture also created Ulnala Prefecture, with its capital at Legwai (which is how the Xinguo-Koreans pronounce Rekwoi, one of the principal Ao’er towns in precontact times). Situated near the mouth of the Ao’er River, Legwai is the port of entry for the whole heartland of Ulnala. New arrivals from Asia, tribute being sent to Ningbo, Treasure Fleet goods being sent from Ningbo; all of it passes through Legwai. It became a rapidly-expanding boom town that far outstripped the size of the sleepy little Ao’er town it had once been.

By the end of the 15th century, few full-blooded members of the Ao’er, Gadu, Huba, and Qinginghui nations remained. In their place had risen a hybrid cutlture of people with both Korean and Aogahu heritage. These people, who make up about a third of the modern population of Ulnala, became known as the Cheon Dul (or Chuan’er in Mandarin), which roughly means ‘string together two’.

Things had changed so radically by then that the Cheon Dul had trouble keeping up. Large-scale feuds died down after the turn of the century as the prefectural government tightened its grip over the countryside, but at the same time Legwai was able to impose a more Korean-style legal system on the population. Since the time of the first settlers, laws had been highly localised so that laws that applied in one village often did not exist in another.

From about 1500 onward, Legwai sought to simplify the legal system by standardising the many local laws into a single, coherent structure that could be applied everywhere. This turned out to be a trickier ambition than anticipated. Since precontact Aogsahu didn’t have a written language, the law was based on verbal agreements rooted in a fluid tradition that was both ancient and yet subject to change over the course of generations. When settlers had begun purchasing land in the 1450s, they had done so within the existing Aogahu framework. From 1473 onward, it became more common for land deals to be made in writing. However, since Legwai’s influence beyond its own immediate hinterland was limited, there was no standard format for such agreements to take. Contracts could be written in Korean using the Korean alphabet (hangeul), or in Korean using Chinese characters, or in Chinese. Needless to say, very few Aogahu and their Cheon Dul descendants understood any of the three. In lieu of reading such contracts for themselves, they were told its contents by those who had written them, but what was written and what was said were not always the same thing. The result was a whole lot of contracts, whether written or verbal, in which the two signatories could not agree on what the contract actually was.

To make sense of this mess, a legal team was appointed by Prefect Park Dong-jun in 1534, and they opened the Special Court for Resolving Land Disputes, colloquially called the Land Court. Instantly, the court became clogged with long, drawn-out cases over land ownership. Most disputes had no real resolution that could be made, since it was a “he said, she said” situation. Before long, disputes began to be resolved primarily through bribery and personal connections. Under these conditions, the winners were those who were both rich and most knowledgeable about the unspoken rules that governed backroom dealings of this kind. Naturally, this turned out to be Xinguo-Koreans, since the Land Court was also staffed by Xinguo-Koreans. Park Dong-jun also intervened in a number of cases to make sure his friends and relatives had their cases resolved in their favour. He also had several land dispute cases of his own and, naturally, all of them were resovled in his favour.

At the same time as the Land Court was corruption-ing its way through a stack of land disputes, Park Dong-jun had other people working on devising a whole new standardised legal framework. Aspects of the traditional Aogahu legal framework were retained, altered and synthesised with a fundamentally Korean legal framework and then imposed uniformly across Ulnala.

Between the corruption of the Land Court and the imposition of a whole new system of laws, a series of revolts occurred from 1535-1540. Ironically named the Legal Revolts, most were led by Aogahu and Cheon Dul chiefs who controlled land that was under dispute or who felt their land had been unfairly awarded to someone else in one of the many cases the Land Court handled.

Every time a revolt was crushed, the rebels were executed—often by the most brutal of methods, such as impalement or being boiled alive—and their lands were stripped away from their surviving family members to be given away to those loyal to Legwai. The primary beneficiaries of this land redistribution were Xinguo-Koreans with little to no Aogahu blood in them.

In this way, Cheon Dul and Aogahu people had become little more than an oppressed underclass by the 1550s. Strictly speaking, there was no racial caste system. Xinguo-Koreans were not universally wealthy, nor even universally wealthier than Cheon Dul. A handful of Cheon Dul families could trace their ancestors back to precontact times and still held onto lands their families had owned then. However, Xinguo-Koreans controlled a disproportionately high amount of wealth in the prefecture. From the wealthy merchants who brought Ulnala’s bounty to the Treasure Fleet every year to the filthy rich magnates who rented out vast tracts of land to poor families who lived in grinding poverty, most of the wealthiest people were Korean in origin and had little to no Prior blood in them.

Through his control of who got deeds to what land in the new legal system he devised, Park Dong-jun was able to entrench himself as essentially a petty soevereign over the prefecture. His family would continue to dominate Ulnala’s politics for generations.

All was not lost for the Cheon Dul and their full-blooded Prior cousins. Like the Minwei, the Cheon Dul still practice many of the old festivals. In precontact times, the world the Aogahu inhabited was very small, since they rarely travelled far from home. They developed a highly localised worldview, and so their festivals were tied to very specific locations that held special significance. Some of these locations have since been built over and are privately owned by people who are indifferent to their meaning. Others, however, are under the control of religious or cultural institutions that still hold ceremonies there to this day. A few have been declared world heritage sites.

We will discuss the Cheon Dul and Aogahu more as they come up in the narrative.

When Wei Yonglong became Master of Two Provinces in 1589, Ulnala Prefecture was ruled by Prefect Park Jae-yong, a descendant of Park Dong-jun. As with Redwood Prefecture, Wei Yonglong demanded higher taxes and received them; in exchange, he left the Park family alone to rule the prefecture as they saw fit and always selected the Parks’ chosen successor as prefect. Thus, just as the Weis had come to be kings of North Province in all but name, the Parks became kings of Ulnala in all but name, but did so under the auspicies of the Weis.

2.3 – A Survey of Yiwuxian Prefecture (1437 – 1589)

Yiwuxian Prefecture is located on the traditional territory of the Two Magala Nations, namely, the Northern Magala and Southern Magala, the latter of whom is more commonly called the Maodou. They speak mutually intelligible dialects of one language and are culturally indistinguishable to outsiders. Magala can be spelled several ways and is derived from the Magala word Maklaks, which means ‘person’. Maodou is derived from Moatokni, from Moatokni Maklaks, which means ‘Southern People’. Each was centred around a lake, with the Maodou living around Onion Lake while their Northern Magala cousins lived around the much larger Yiwuxian Lake, out of which issues the Gamaduan River. Further down that river, of course, lie the Jiahousadi, Gadu, and the Ao’er, none of whom are related to the Magala, who speak a Penutian language. Their Penutian, however, is part of the Plateau branch of the language family; unlike Penutian more generally, which remains a hypothetical language family, Plateau Penutian’s status as a language family is not in dispute. It is, therefore, the southern spur of a larger family that includes Cinong, Yajina, Palusha, Nimipu, and others.

Contact was made with the Magala by Korean explorers in the 1480s, but the first settlement was established in 1491 by a guild of Min-speaking fur traders called the Inland Exploration Society. A strip of land was purchased from local Northern Magala people on the banks of the Gamaduan not far south of where the river exits Yiwuxian Lake. At the beginning, it consisted of three blockhouses joined together by a palisade and was called Maodou House. Later, it would develop into the bustling frontier town of Maodou City, capital of the prefecture. Its location was strategically chosen for ease of access to both of the Two Magala Nations and for the purpose of blocking rival fur traders from accessing Yiwuxian Lake.

As an aside, there is an amusing story behind the name of Yiwuxian Lake. Korean fur traders called it Magala Lake, for the people who lived there, but the Min traders called it Yiwuxian Lake, derived from E-ukshi, which is the lake’s native name. Generally speaking, Chinese names derived from native ones use a random jumble of Chinese characters that sound similar to the native syllables in an attempt to represent them using China’s not-at-all-designed-for-American-phonologies writing system. Yiwuxian was originally spelled Yīwǔxiàn, or依侮憲, which roughly translates to “lean on insulting the law”. As a rule, the meanings of the characters used are irrelevant because the goal is to transcribe something from another language, not to construct a coherent sentence. “Lean on insulting the law”, however, was considered a deeply inasupicious name, if not outright seditious. It was first written down by a clerk at Maodou House in a routine report on the transfer of goods to Maodou House from Magala settlements on the lake. When questioned later, he claimed he simply spelled it how he’d heard it pronounced by fur traders who dealt with the natives on the lake. After Yiwuxian Prefecture was created in 1507, the first prefect banned that spelling for the lake and decreed it should instead be called Yīwūxiàn or 依屋憲, which translates as “lean on house law”, which doesn’t make any sense but at least it didn’t increase the heart palpatations of government officials worried about potential rebellious implications hidden in lake names. Besides, it contains the character for ‘house’, which is part of Maodou House, and so it was a nice callback to the name of the trading post Maodou City had been founded on.

Fines were levied agaisnt those who used the banned spelling. Because the prefect had deliberately chosen a replacement character that is pronounced similarly but uses a different tone, he could also levy fines against those who pronounced it according to the illegal spelling. However, where previously the old spelling was just a funny quirk of transcription, the act of making the old spelling and pronunciation illegal gave it power among those who actually did harbour ill feelings toward the prefect’s government. Yīwǔxiàn became the standard spelling in Ulnala Prefecture (whose people held a grudge against Yiwuxian Prefecture for reasons we’ll get into later in this section). Those inside Yiwuxian used it as a rallying cry for those who were discontent with the government. People would spell it the old way in secrete communiques and would even pronounce it the old way in public as a dog whistle. Enforcing a fine against people who pronounced a word slightly different from the acceptable pronunciation was, of course, almost impossible. In the unlikely event that someone reported an offender to the authorities, the offender would claim it was done out of habit because of having said it the old way for years, or they would say it was an accident, since wǔ and wū are so similar.

Getting back on track, the main rival to the Inland Exploration Society was the Weicheupuseu Earth Fur Society (“Earth Fur” distinguished the society as one that traded for the furs of inland mammals such as beavers as opposed to “water fur” trading societies that traded for or hunted the furs of sea mammals such as otters and sometimes hunted whales). Weicheupuseu had been one of the principal towns of the Ao’er in precontact times located at the confluence of the Gadu and Huba rivers (which together form the Ao’er River), which is also the border between the Ao’er, Gadu, and Huba nations. It was the perfect location for an Ulnala-based business with interests in the interior to place its headquarters in.

Now, looking at a map, it may seem like the Weicheupuseu Earth Fur Society would have a distinct advantage in reaching Magala country over any society based out of Redwood Prefecture, which is where the Inland Exploration Society came from. After all, from Weicheupuseu, all one has to do to reach Magala country is go upriver. The river Maodou House was built on is the same one that Weicheupuseu is on, even though it has three different names (when it exits Yiwuxian Lake, it’s called Gamaduan River; after it’s joined by Aoluoweichala River, it’s called the Gadu River; and after the Gadu combines with the Huba, it’s called the Ao’er River; for simplicity, the full length of the river may be called the Aogaga). This is true; however, the rich and influential people of Ulnala were focused more on expanding up the coast and into the interior along the Yanshu River and were mostly content with leaving their frontier at the traditional boundary between the territories of the Gadu and Gamaduan peoples, which was not far below the confluence of the Gamaduan and Aoluoweichala rivers.

In Redwood Prefecture, however, there was nowhere else to expand after they’d conquered the Eel River country from the Prior tribes there. 1491 saw the first written treaty made between Magala and Xinguans when the Inland Exploration Society purchased a tract of land from the Iu’laloηkni tribe of the Northern Magala Nation. This wasn’t an official treaty, however, since it didn’t have the backing of then-governor Wei Dongshi. In 1495, the Inland Exploration Society was given the right by Wei Dongshi to sign official treaties on his behalf. Yiwuxian was part of North Province, and North Province was part of Ming, and Ming only allowed diplomatic and commercial ties with peoples who ackowledged the Ming emperor as their ultimate sovereign. Wei Dongshi had the right to establish tributary relations with peoples in America on the emperor’s behalf. Thus, by giving the Inland Exploration Society the right to sign treaties, Wei Dongshi was, in effect, giving them the right to establish new tributaries for the emperor of China.

The society exercised the right that same year (1495) when they called the Grand Everlasting Friendship Conference in Maodou House and invited all chiefs from the Two Magala Nations to attend. The chiefs signed the Maodou House Everlasting Friendship Treaty. Its major points were these:

- The Two Nations acknowledge the Emperor as sovereign over them.

- The Two Nations will send an annual embassy to present tribute to the Emperor or his representative.

- The Two Nations shall be permitted access to markets in China.

- The Two Nations shall be protected from their enemies by the Emperor and his representatives.

What the treaty meant was that the Magala would send a tributary embassy to Ningbo every year (Wei Dongshi had given the Inland Exploration Society the right to establish tributaries, but not the right to receive tribute). Tribute came in two forms. First and most important was that the delegates would have to perform the kowtow to the governor (although it was a much less elaborate form of the kowtow than the one that would be performed for the emperor himself). Kowtowing is an act of prostration performed by a person toward their social superior. It can be done in many contexts and to varying degrees of ritual. At its most basic level, the one performing the kowtow began by standing up, facing toward the recipient. They would kneel, then bow down on their hands and touch their forehead to the floor before getting back on their knees and then standing up (if a commoner was presenting a petition to a government official, however, they would remain kneeling). The whole thing might be repeated multiple times. If one was kowtowing to the emperor, for example, one was to kneel three times and prostrate themselves three times for each kneeling in a process described as “three kneelings and nine knockings of the head on the ground.” In Xinguo, protocol demanded that a tributary embassy perform one kneeling and three knockings of the head on the ground.

Naturally, this was considered to be deeply degrading by the Prior nations of America. However, the benefits generally outweighed the costs. For example, entering into a tributary relationship was usually a good safeguard against being invaded and massacred.

The second tribute came in the form of physical goods—usually fur, since that’s the most interesting export good the Magala had access to. Out of magnanimity, the governor would spontaneously gift the delegates with goods of Xinguan and Chinese manufacture, most often weapons and tools made of metal, as well as luxury goods such as silk and porcelain. Of course, the governor’s “spontaneity” never failed to bestow such gifts. While it would be uncouth to make the exchange of goods an explicit part of the bargain, it was understood to be a part of it nonetheless.

This was the second benefit of sending tributary embassies. The annual influx of manufactured goods and luxuries became an essential part of the Magala’s economy. It was, in essence, trade dressed up as tribute. It was, however, a highly centralised form of trade. Delegates returning with the goods they’d received handed those goods over to the chiefs who’d signed the treaty, and those chiefs chose who to distribute the governor’s gifts to. In theory, everyone contributed equally to the tribute, and everyone benefitted equally from the gifts given in return. Practically speaking, however, the chiefs could simply refuse to distribute gifts to those who displeased them. This began a process of centralisation and—in the eyes of the Xinguans—civilisation. It was the makings of something resembling a government to replace the informal, ad-hoc delegation of power based on personal influence that the Magala had relied on previously.

The Magala chiefs who signed the treaty, however, could not read Chinese and were therefore under the impression that the mutual exchange of goods was explicit in it, since that’s how it was explained to them verbally before they signed it. At least, that’s what Magala oral stories record. Whether it was explicit or implicit was not to become relevant until over seventy years after it was signed, however, since that’s how long it took before the first time the governor’s spontaneity failed him.

The treaty also promised imperial protection against enemies, which will become relevant later. Another interesting quirk of the treaty is that it technically gave the Magala the right to send a delegation all the way to China to meet the Emperor himself (a right that they did actually take advantage of from time to time), and it enabled them to trade in China itself, not just in Xinguo.

For now, however, what you need to know is that the only part of the treaty that the Inland Exploration Society actually cared about was the third point; establishing the Two Magala Nations as an official tributary of China legalised the trade between the Inland Exploration Society and the Magala, which up until that point had been legally classed as smuggling. Maodou City thus became the centre of all commercial interaction between the Magala and Xinguo, with the exception of the yearly trip to Ningbo.

Meawnhile, the Weicheupuseu Earth Fur Society had much less powerful backers and only began to contest the Inland Exploration Society’s claim to the Magala country after the latter were already established there. Since Maodou House was blocking access to Yiwuxian Lake, the Weicheupuseu Society had to establish their outpost further downriver at the Kammatwa village of Kutsastus. The Xinguo-Korean name for Kutsastus was Kasaseutuseu, and so their trading post there was named Kasaseutuseu House.

Kutsastus was in a great position to trade with the Kammatwa (for whom the Gamaduan portion of the Aogaga River is named) and nearby Ahotireitsu, but it placed the Weicheupuseu Society at a disadvantage when it came to trading with the Magala. It was possible to pass Maodou House, but anyone doing so who wasn’t from the Inland Society was harassed, intimidated, and sometimes had their goods seized (which was illegal, but it was done anyway). The alternatives were to go around Maodou House—a lengthy detour that necessitated leaving one’s boats behind at Kutsastus and going overland—or to attract Magala traders to come to Kasaseutuseu House.

Deciding the latter was preferable, the Weicheupuseu Society set their prices lower than the ones the Inland Society was willing to sell at. They were able to do this because, despite having less clout and fewer resources to call upon, their goods could be carried from Weicheupuseu to Kasaseutuseu House by simply loading it on boats and paddling upriver. A few unnavigable sections notwithstanding, the the trip up the Aogaga is trivial in comparison to the overland route crossing rivers, canyons, and mountains that the Inland Exploration Society had to take to get from Redwood to Yiwuxian.

Of course, the Inlanders tried using the route up the Aogaga as well, but there were two problems with this. Firstly, the Weicheupuseu Society may have been a small fish in a big pond when it came to Ulnala politics, the Inland Society had no presence there at all—in large part thanks to the other power brokers of Ulnala viewing the Chinamen from Redwood as foreigners and therefore an unwelcome influence. With the government already sympathetic to the Weicheupuseu Society, it was easy for the latter to lobby the government to hamper the Inland Society’s operations in the prefecture. The second problem for the Inlanders was that, by trying to go up the Aogaga River to Maodou House, they now had to go past Kasaseutuseu House, which reversed the advantage they had over their rival.

All this meant that the Inland Society was operating at a thin profit margin and would quickly lose everything if they tried outbidding the Weicheupuseu Society. And so they fought fire with a nuclear explosion.

Kasaseutuseu House received business from the Northern Magala and Maodou, and also sent merchants to trade in the latter’s territory, since it wasn’t blocked by Maodou House. However, the trading post also became a hub of trade for the upper Kammatwa villages and the Ahotireitsu. These were two tribes of the broader Jiahuosadi nation (although the Kammatwa seem to have originally been composed of two or three tribal divisions of their own that the Xinguans treated as one unit), which itself was part of the even broader Plain Speakers group.

Strictly speaking, trading with the Kammatwa and Ahotireitsu was smuggling, because neither one was a tributary of China. However, smuggling of this kind happened all the time on the frontier. It was overlooked by the provincial government because the governors generally saw it as a good way of introducing civilsation to the Priors and thereby encourage them to become tributaries, which would then enable the government to buy land from them or demand it as tribute. Paying money for land was preferable to outright invading Prior territory and seizing it by force, since it was cheaper in both money and Xinguan lives. However, it did mean that Kasaseutuseu House was engaged in open smuggling operations, which left the door wide open for the Inland Society to strike at their rival.

In 1507, Yiwuxian Prefecture was created, although its borders were not yet entirely clear. A contention arose that year over its southwestern frontier. Yiwuxian Prefecture laid claim to the whole length of the Gamaduan River (which is the section of the Aogaga River down to Chitatowoki Village, the first Kammawtwa settlement on the river and forms the traditional border between the Kammatwa and the Gadu). Ulnala, however, contested this claim by counter-claiming the river up to Kasaseutuseu Village, which is the last of the Kammatwa settlements and forms the traditional border between the Kammatwa and the Two Magala Nations. The Inland Exploration Society tried resolving the issue by getting the Kammatwa, Ahotireitsu, and Iruaitsu (a third Jiahuosadi tribe who live along one of the Gamaduan’s tributaries) to sign tributary treaties. Both the Weicheupuseu Society and the Ulnala government opposed this because they feared it would mean the three tribes would fall into Yiwuxian’s orbit and thereby resolve the dispute in their favour. As for the three tribes themselves, they were already on good terms with Ulnala, with whom they traded and intermarried. The three tribes declined signing tributary treaties with anyone from Magala or Redwood.

However, although all three tribes got along with Ulnala, they didn’t always get along with each other. In fact, the Ahotireitsu were long-time rivals of the Iruaitsu. Some Ahotireitsu chiefs saw opportunity with Yiwuxian Prefecture. Becoming tributaries under the auspices of Yiwuxian Prefecture would enable them to gain an edge over their ancient enemy. They’d also seen the wealth and power accrued by the Magala chiefs who received the governor’s gifts and craved that power for themselves.

Together with a few chiefs from the upper Kammatwa, they signed a tributary treaty with representatives from the Inland Exploration Society. The treaty officially constituted the Kammatwa, Ahotireitsu, and Iruaitsu tribes as the Jiahuosadi Nation, with those chiefs who signed the treaty being recognised as the nation’s leaders. They were called the Treaty Chiefs. The treaty was kept secret until later that year, when the first tributary embassy was sent to Ningbo. At first, the reaction was muted. Chiefs from some of the other Ahotireitsu and Kammatwa villages complained that the Treaty Chiefs treaty had broken solidarity, but ultimately they had the right to sign treaties for their own villages. However, it had not yet become clear that the Treaty Chiefs hadn’t signed the treaty on behalf of their own people, but rather on behalf of all three Jiahuosadi tribes.

The next year (1512), the Treaty Chiefs reported to then-governor Wei Changhua that they’d uncovered a treacherous plot to overthrow the provincially-recognised government of the Jiahuosadi, and it revolved around a smuggling ring based out of Kasaseutuseu Village run by Korean merchants from Ulnala. They requested aid from the provincial government and from Yiwuxian in crushing the rebels and rooting out the smuggling ring. Wei Changhua, who was only dimly aware of the situation on the ground, granted the request and sent 500 soldiers of the Black Banner Guard to help deal with the problem.

The result was the Gamaduan River Expedition. Together with Yiwuxian prefectural militia and allied Jiahuosadi warriors, the Black Banner Guard marched down the Gamaduan River and up its tributaries crushing any and all resistance they encountered. They also attacked Kasaseutuseu House. The merchants tried to surrender, but the Yiwuxian and Jiahuosadi leaders convinced the Black Banner Guard general in charge of the expedition to turn down the surrender. Instead, the trading post was seized by force. All prisoners were executed on charges of smuggling and inciting rebellion, and the whole village was burned to the ground. Hundreds, perhaps thousands Jiahuosadi were massacred in attacks on supposedly rebellious villages. Hundreds more were enslaved and sold to cover the costs of the expedition and line the pockets of the Xinguan officers and the Treaty Chiefs.

The next year (1513), the Yiwuxian-Ulnala border dispute was resolved by Governor Wei Changua in Yiwuxian’s favour.

At the same time as all this was going on, Yiwuxian was opened up for settlement. Poor and landless people from Redwood began migrating there and settling on the far upper reaches of Aogaga River and the lower portion of Yiwuxian Lake. Likewise, employees of the Inland Exploration Society would settle there when their employment contract was up. Small numbers of Korean and Cheon Dul settlers arrived from Ulnala as well, even though the government tried to keep them out.

And so it was that Yiwuxian Prefecture grew up as something of a colony of Redwood Prefecture. Although it was politically autonomous, it was dependent on Redwood economically and for the inflow of new settlers.

Over the decades, Yiwuxian remained a frontier prefecture. Its population was small, its level of development relatively primitive in comparison to the Valley or the coastal areas of Redwood and Ulnala. Prior nations in the prefecture still held onto a great deal of their traditional lands and remained major players in the economic and political life of the prefecture.

[Next]

Leave a comment