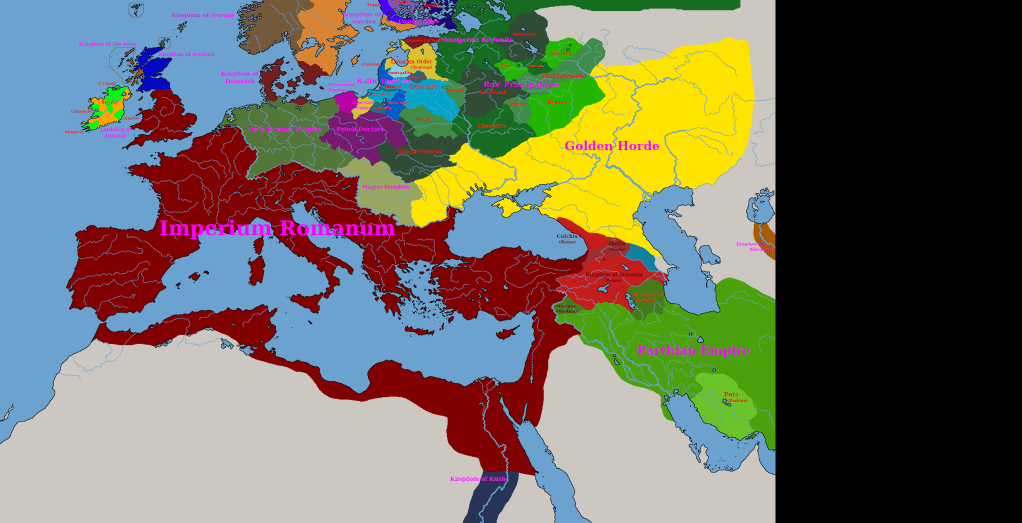

What if The Roman Empire—But Also Medieval Europe?

[Next]

It is January 29th, 98 AD. Nerva Augustus has died, but news has yet to travel to his adopted son and designated successor, Trajan Caesar, who presides over the province of Germania Superior from the capital of Mogontiacum on the banks of the Rhine River. Even if Trajan had known that he has inherited the title Augustus, however, his mind would nevertheless have been too distracted to focus on the task of consolidating power, and the reason for that is that there is a city on the other side of the Rhine that had not been there the day before. Impossible though it is, no amount of eye-rubbing will cause the incomprehensible vision of row upon row of houses of an unrecognisable design lining cobblestone streets. People in long tunics and pants slowly fill the streets of that eldritch settlement; barbarian words drift over flowing water to the ears of the perplexed Romans. Some of the barbarians converse with each other while others wander around in a daze, but all appear to be just as confused as their new neighbours.

Indeed, the good citizens of the Free and Imperial City of Wiesbaden have every reason to be confused. Yesterday, they’d gone about their business like any other day in the Year of Our Lord 1250, but this sun had dawned on the military barracks of an unknown army instead of the city of Mainz. All up the Rhine and down the Danube, the same story repeats itself at every settlement you care to visit on that strange day; people see new settlements that had not been there before, or notice the absence of those that should’ve been there, or, as in the case of Wiesbaden, see a whole city replaced with a different one. Consternation does not begin to describe the state of absolute pandemonium that has broken out this day.

People on both banks wonder what’d become of family members and property that’d been on the other side. Curiosity leads some to cross the river to find out what was going on. Often, they encounter people from the other side doing the same. Many, if not most, of these encounters end peacefully. But not all. Not here at Wiesbaden.

Here is Fritz, a simple serf from the area of Wiesbaden. Like many another German man of the 13th century, he is fair of hair and eyes. Together with his younger brother Hans, Fritz rents a field on the other side of the Rhine. Wondering what has become of that field, Hans takes up a spear and shield while Fritz takes the family woodaxe, and the two men cross the Rhine to find their field. They have not gone far from the banks when they are met by ten men on horseback wearing mail and wielding javelins and swords. They yell in an unintelligible language and kill Fritz, but Hans leaps into his boat and manages to get back to the other side, where he takes a moment to collect himself before hurrying to Wiesbaden to tell a certain man of what has occurred.

Now meet Torsten von Biebrich, the man Hans seeks. Torsten is a knight from the area and is Fritz’s liege. Outraged at the brazen murder of his serf, Torsten calls upon his brothers and cousins, gathering an army of eighty men and twelve knights Taking up arms and armour, the men cross the river just two days after the appearance of the strange army camp in place of Mainz. Before long, they come across a group of the men Hans had encountered and they kill them. Over the next two days, they enounter several more patrols and defeat them. They also raid any farms they come across and pillage a village, taking all of the strangest things with them, and even capturing a few people. More importantly, they find nothing on this side of the river is as it had been on January 28th. Torsten’s lands and serfs are gone, as is Fritz and Hans’s field. Only the lay of the land itself is familiar; everything else, from the people to the growth of the forest, or the settlements and layout of the farmers’ fields is totally different from what Torsten remembers from touring his lands on this side of the river only a few days ago.

Torsten returns to Wiesbaden on February 2nd, where he informs the city fathers of what he has seen and presents them with equipment and booty captured during his raid, including the six captives he has taken. Upon examination of the captives, the city fathers realise that they speak Latin and call upon a local priest to translate for them. Although the dialect the captives speak is very different from the Ecclesiastical Latin spoken by the priest, they are able to make themselves understood well enough to explain that they are citizens of the Roman Empire and that Governor Trajan will surely avenge the wrong committed against them these past days. This is rather confusing to the city fathers, who reply that they are all subjects of the King of the Romans, whose name is Friedrich II, and this inconsequential skirmish is not likely to warrant his attention. Also confused, the captives insist that there is no Friedich, much less a second one, nor is there any king of the Romans, but there is instead an Augustus by the name of Nerva, and his officer Trajan will most certainly avenge this outrage. More confused now than ever, the city fathers turn the captives back over to Torsten for further questioning.

Meanwhile, across the river in Mogontiacum, Trajan Caesar is making plans. He has reviewed the intelligence gathered so far concerning these newcomers on the opposite bank. From men in watchtowers straining their eyes to take in all they can see to people captured or killed crossing onto the Roman side, there isn’t much to go on. Furthermore, something must be done about the raid conducted by the newcomers only days ago. As such, Trajan commands Tribune Aulus Platorius Nepos to take 1000 men across the river to scout the new lands and assess the city’s defences.

Nepos crosses the Rhine a few days later, on February 9th. He crosses at Bingium, a Roman fort just upriver from Wiesbaden, and finds himself in a section of land that belonged to the Archbishop of Mainz; since the Archbishop of Mainz does not yet exist, he is not here to organise a defence of this orphan territory, so Nepos effortlessly pillages his way across it in his first day in Germany. By the second day, the citizens of Wiesbaden have heard of what’s going on and panic ensues as all the people in the countryside flee into the safety of the walls. The city fathers muster as many men as they can on short notice; these 500 men are simple urban militia wearing helmets and gambesons, wielding spears, guisarmes, and crossbows. A handful of knights lead them. They clash with Nepos on the banks of the Rhine, where the knights and their men at arms route the Roman auxiliary cavalry, but the Roman infantry carves a bloody path through the Wiesbaden lines and crumble them to ruin. Wiesbadeners flee for their lives and are cut down in droves. With nothing left standing in his way, Nepos pillages the countryside around the city, including the village of Biebrich. Our man Hans barely escapes the village with his brother’s widow and her infant son just before the Romans arrive; they flee not to Wiesbaden, but eastward, in the direction of the larger and more powerful city of Frankfurt. Torsten von Biebrich, who fought in the battle, must also flee his manor house with his household and take refuge in Wiesbaden.

Now Nepos arrives at Wiesbaden as dusk falls over the Rhine and looks up at the city’s grand defences. They have seen better days. The crenellations have been heavily damaged, leaving huge sections of wall exposed to missiles from besiegers. City gates, once mighty bastions beckoning an attacker to close distance and step into their killzone have obviously been destroyed recently and the repairs since then have been haphazard and slap-dash. Furthermore, refugees are fleeing into the city; the gates cannot be closed for the throngs pressing inside, and the throngs cannot be pushed back for want of city guardsmen to do so.

The reason for all this devastation is that eight years in the future’s past, the Archbishop of Mainz had a disagreement with the good citizens of Wiesbaden; he besieged the city, wrecked its defences, and sacked it, leaving it broken and dejected.

Nepos assesses Wiesbaden’s defences and concludes the city will fall at the slightest nudge. Rather than reporting back to Trajan and waiting for orders, Nepos presses the attack there and then. His men fall upon the refugee columns, who instantly melt away into the countryside; forcing their way through the still-open gates, and into the streets, they slaughter every man who stands in their way. Before the sun has finished setting, the city fathers send one of their number with a priest to surrender the city to the Romans. Nepos, though surprised to meet someone who speaks Latin (albeit very badly), accepts the city’s surrender. He liberates Torsten von Biebrich’s captives and takes a hefty sum in silver, gold, and other valuables handed over by the city fathers, and takes his leave, returning to Mogontiacum.

There, he tells Trajan of all that he has done. Trajan is surprised his man so easily captured a city and is easily convinced that these newcomers are really no more serious a threat than the Germans who came before them.

But the story of the Two Romes has only just begun. This unexplained, incomprehensible event, this Act of God that brought the two timelines together will resound throughout the ages to come.

[Next]

Leave a comment