7.1 – Rumblings of Discontent (1590s)

As the decades went by, the Western Children Sect grew in popularity and spread throughout South Province and into the North. Its adherents were almost exclusively poor people with just a sliver of the lower crust of affluent people being involved with it. This, coupled with the outlook of its founder and anger at the injustices she suffered over the course of her life led the Sect to develop a strong sense of justice for the poor. In addition to performing ceremonial dances—some in secret and others in public—and continuing to spread their founder’s teachings, the Western Children took up alms for the poor, widows, and orphans. They were also anti-foot-binding, becoming the first organisation in Xinguan history to be avowedly against the practice.

The people most likely to join the Western Children were from the poorest and most marginalised echelons of society: slaves, peons, prostitutes, landless peasants, day labourers, and beggars.

For a long time, the Western Children did not appear on the radar of the provincial governments. If the governors even knew they existed, it was only a dim awareness of them as one of the many folk movements poor people took part in. Local officials at the prefectural and county levels of government periodically harassed and persecuted Western Children and similar movements, but there was never any provincially-organised persecution campaign.

Things continued this way until the 1590s. Initially, the magnate consolidation of the late 1580s and early ’90s had little effect on the peasantry, as it was mostly the Southern magnates who were being stripped of their lands. As time progressed into the mid- and late ’90s, however, the Northern magnates who now dominated land ownership throughout Xinguo got greedier and greedier. Landowners of more modest means had their land stripped away as well, poor peasants were forced into debt servitude, and those who couldn’t pay rent or debt instalments were sued for their topsoil rights more vigorously than before.

Magnates enriched themselves at the expense of everyone else; peasants and even members of the gentry were forced deeper into poverty and had to take jobs working on farms now owned by the magnates and operated by hired managers. Most of these managers were Northerners, often with family connections to the magnate they worked for; their goal was to make as much money in the South as possible and then move back to the North, which incentivised them to exploit the workers as harshly as possible in order to maximise short-term gains.

In this economic climate, pre-established secret societies such as the Western Children, the Guhuma Sects, and the White Lotus became ways for the most oppressed people to organise and fight back. They helped people with evasion of taxes, rent, and debt payments, provided legal aid, and took food donations to feed those who were starving.

Resistance was not only passive, however. In desperate times like these, some people turned to banditry, preying upon others who had only slightly more than they did. Secret societies helped organise self-defence militias to fight back against the bandits. From fighting bandits, it seemed a small step to initiate armed resistance against the government. Weapons were not hard to come by because Xinguo had a strong weapons-culture arising from many years of frontier existence living in fear of Prior raids. Most households had at least a spear, probably a club or two, and perhaps an axe or a halberd, glaive, or other polearm. Crossbows were common too, since they were relatively cheap and easy to use.

What was much less common was the musket. Having been imported to Xinguo from China in the 1570s, the musket was a major improvement in firearm technology; it was a true weapon of the early modern age in contrast with its medieval predecessor, the fire lance. However, they were mistrusted by Xinguans whose fathers and grandfathers had trusted in fire lances to carry them to victory in the wars of generations past. Consequently, use of the musket was confined to the Black Banner Guard, the professional soldiery of North Province. In fact, in 1593, Wei Ruzheng had made it illegal for anyone but the Black Banner Guard to own muskets. Fire lances were almost exclusively used by provincial militia members and could only rarely be found in the hands of random civilians.

Starting in the late 1590s, clashes began breaking out between government troops and rural militias.

7.2 – Great People’s Revolt (1608 – 1614)

In response to “increasing banditry in Southern rural areas”, Wei Taixun issued an edict in 1608 banning peasants in the South from owning gunpowder weapons of any kind “For the safety and security of the people”. Later that same year, he doubled down by banning swords and polearms (except for spears) as well. In accordance with these bans, the Black Banner Guard and provincial militia carried out a series of sweeps through the Southern countryside to harass and intimidate peasants and seize any banned weapons they may be in possession of. Build-up to an upcoming sweep as done in secrecy, and the sweep was launched without announcing ahead of time where it was to be conducted.

Western Children militias were the obvious target of both the weapons ban and the sweeps, but everyone was caught up in it. Without weapons, people were defenceless against actual bandits in the countryside, pirates from Ryōseikoku, and hostile Priors from beyond the frontiers. Angry people joined the Western Children or formed their own organisations. Rural militias resisted government sweeps by moving weapons to hidden stockpiles. Government armouries quickly filled with seized weapons, which enabled corrupt officers to sell the seized weapons on the black market, where they were often purchased by the same people they’d been seized from in the first place.

Tensions were already high before the weapons ban; people in the South were already angered by the North’s aggression, by the wealth transfer into the hands of Northern magnates, and by the expansion of debt enslavement. When the Northerners came for people’s means of self-defence, there was a torrent of rage directed at the government and at Northerners in general. Thus began what the Southern peasants called the Great People’s Revolt, but which the government simply labelled Southern Banditry.

The Great People’s Revolt was not a conventional war. Aware that they couldn’t fight government forces in the open, rural rebels avoided conflict on unfavourable ground. The revolt took the form of an ongoing process of government sweeps, skirmishes, and assassinations. Rebels assassinated government officials and the hated managers who operated magnate-owned farms in the South; government forces responded with sweeps through areas suspected of containing rebels; rebels fought back with traps and ambushes.

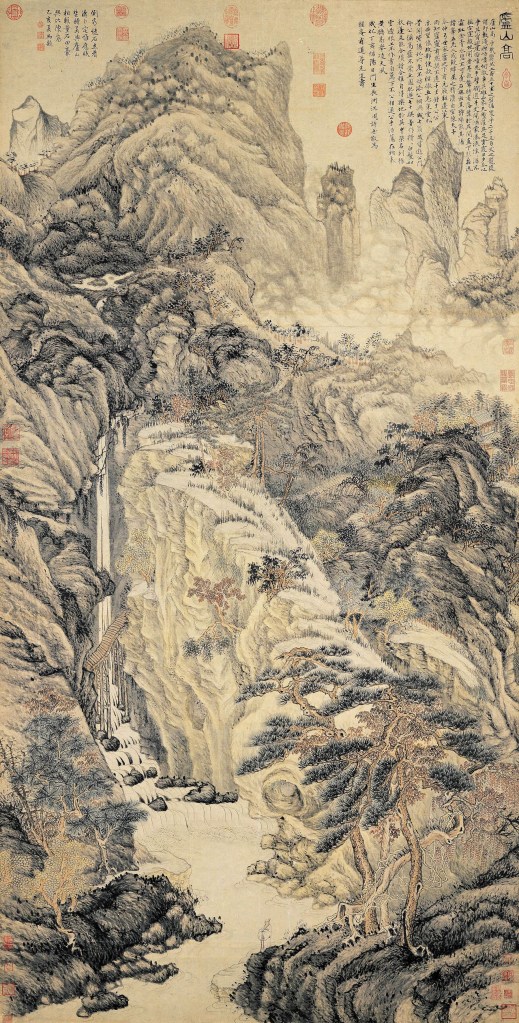

Fighting in the flat, open expanse of the Valley usually went in the government’s favour, since there was nowhere for the rebels to hide from government cavalry forces (including the feared Tatar horse-archers), so rebels took refuge in the mountains and in underground cells in the cities. Securely tucked away in mountain strongholds, rebels fortified their positions and learned how to use ambush tactics as a force-multiplier to destroy larger, better-equipped, and better-trained government forces in the narrow passes and treacherous highland trails of the Burning Coast Mountains and the Golden Mountains. Some areas became no-go zones for regular government patrols because of the high cost in treasure and blood to keep them secure.

Besides the Western Children Sect, there were also militias associated with the Guhuma Sects and the White Lotus, as well as other folk sects, including militias led by Daoist and Buddhist warrior-monks. Most rebels were in the South, but not all. Concurrent rebellions broke out in the North among the Cheon Dul of Ulnala, the Minwei of Redwood, and the Meixiaze of Meixiaze Prefecture; all of these peoples had previously been legally recognised as Priors but had that status revoked by Wei Yonglong. Rebellion in the South gave them the chance to revolt as well.

Still, the largest, most powerful, and most coherently-organised rebel group were the militias associated with the Western Children Sect. With members throughout South Province and in much of the North as well, they did not want for new recruits, nor for sympathisers willing to hide rebel fighters or run interference for them. Being relatively egalitarian, the Western Children recruited female fighters and even many of the leaders were women.

Through their connections in the North, the Western Children were able to establish a rebel cell in Ningbo itself, which became the group who managed to assassinate none other than the Master of Two Provinces himself, Wei Taixun. His son and successor Wei Qiangfang initiated a massive operation called the Grand Sweep to avenge his father’s death.

7.3 – Wealth in the People’s Revolt (1608 – 1614)

While the peasantry put their lives on the line waging war upon the Northern government, the South also had quite a few merchants, business owners, former magnates, and landowners still clinging onto a small portion of the South’s croplands who all had their own reasons to be angry at the Northerners. Former magnates were, of course, infuriated by the seizure of their lands. Many still clung onto small estates, were living off savings, or had invested what wealth they had left into businesses. Once the People’s Revolt started, those who still had money invested it into the revolt. While they did not like peasants and liked the secret societies even less, they did want to restore independence to the South. Someone needed to do the fighting and dying in order for that to happen, and the former magnates weren’t going to do it.

Merchants were maddened at being shut out of the silver trade by the closure of the Dongguang Silver Society. Over its 147-year history, only members of the Dongguang Silver Society had been permitted to buy or sell silver bullion or silver ore. Consequently, they controlled the largest portion of trade with the annual Treasure Fleet, selling its goods both to the rest of Xinguo and also to the Spanish colonies of New Spain and Peru and had gotten filthy rich doing so. In 1597, Wei Ruzheng had forced the DSS to merge into the North Province-based Ningbo Silver Society. In practice, what this meant was that property owned by the DSS and all legal rights it held were transferred to the NSS along with a substantial portion of the wealth and income of DSS members. DSS members had, of course, applied for membership in the NSS, but only a handful made it in. Shut out of the silver trade, many former DSS members lost their businesses. Some were able to adapt, but still had to sell off a lot of property to stay solvent. Others went broke. When the People’s Revolt broke out, many were more than happy to fund militia groups fighting the Northern government.

Wealth alone was not enough to prevent the government from coming after these people. Knowing that the rebels must be receiving funding from somewhere, Wei Taixun went after wealthy Southerners suspected of having ties to rebel groups. In 1612, after Taixun’s assassination, his son Wei Qiangfang dramatically increased efforts to shut down funding to the rebels. After several high-profile executions of merchants and former magnates suspected of funding rebel movements, the rest either went into hiding or fled to China.

Even before this elite migration, however, not all former magnates had been able to stay in Xinguo. In fact, the majority of Southern magnates had either been imprisoned or forced to go into hiding during the 1580s and ’90s. Those who went into hiding slinked away to Xiaweiyi, and many of these went all the way to China, where they began lobbying the emperor for military intervention in Xinguo to restore their positions. As the 17th century dawned, this lobby group steadily grew in size, owing to immigration from those suspected of funding rebels in Xinguo.

Thus, an ever-increasing group of people were telling the Wanli Emperor all about how the Northern government was oppressing the South, and that half of Xinguo was already in open revolt against the North. This, they assured the emperor, was the perfect time for military intervention. Added to this was the fact that Xinguo was not paying the full tribute amount it owed because of the expense of fighting the People’s Revolt, not to mention having to deal with increased banditry and piracy by those exploiting the opportunities opened up by said revolt. If there was ever to be a military intervention in Xinguo, it was going to have to be now.

And so it was that in 1610, preparations for the Grand Armada began.

[Next]

Leave a comment