What if The Roman Empire—But Also Medieval Europe?

It is April 7th, 98 AD. William of Holland’s call to arms is answered enthusiastically by princes all up and down the Rhine. From the Hague to Freiburg, men don gambeson and mail, take up sword and crossbow, and march in the armies of lords and bishops, abbots and counts, margraves and free cities. William personally gathers an army of 30,000 men from the Dutch-speaking region and the lower Rhine, from Münster and Osnabrück, Tecklenburg and Arnsberg, and even a few of the Frisians come despite their own disagreements with William. Smaller armies are gathered by the Counts of Nassau and the Count of Freiburg, with 10,000 and 8,000 respectively.

William marches up the Rhine scattering Heathen raiding parties in orphan territories before entering the County of Berg. Castle Berg remains free, but under siege. At news of William’s impending arrival, the besiegers break off and withdraw. He marches to Deutz. Formerly a suburb of Cologne sitting directly directly across the Rhine from its mother city, Deutz is now under occupation by Heathens. William invests the city and quickly captures it by storming the walls with ladders. The Roman garrison is slaughtered without mercy; even the people of the city strike the Romans in the back as William’s soldiers hunt them through the streets.

Finally, William reaches the Sieg river, which forms the boundary between the mid-sized County of Berg and the much smaller County of Sayn. Trajan campaigned in this area in February, capturing the castles of Sayn, Wied, and Isenburg, as well as the nearby orphan territory formerly belonging to Cologne. Garrisons were left in the castles under the command of Tribune Nepos, who resides now at Castle Reichenstein nestled in the wooded hills above the Rhine.

Reichenstein is a formidable fortress sitting atop a spur of the surrounding hills that incorporates steep hillsides into its design. It would’ve been difficult for the Heathens to capture, but thankfully for them capturing it was unnecessary; the local robber-knight who controls it invited the Heathens in and is now working with them.

William assaults Reichenstein twice, but the Heathens and the robber-knight’s men repel the attacks, so he settles in for a siege. Surrounding the castle with a series of fortified camps, Williams contents himself for a time with using siege engines to hurl stones at the castle and degrade its fortifications while preparing for a more methodical assault.

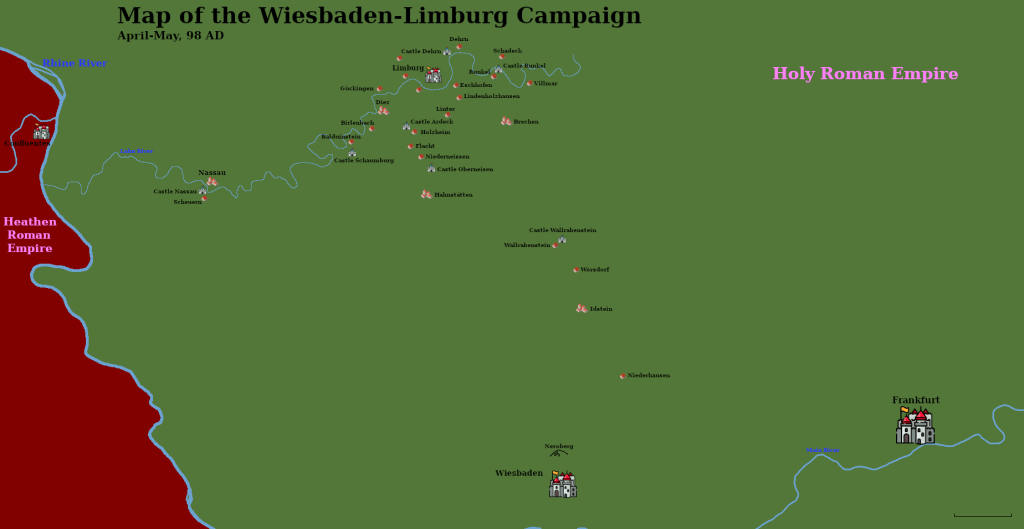

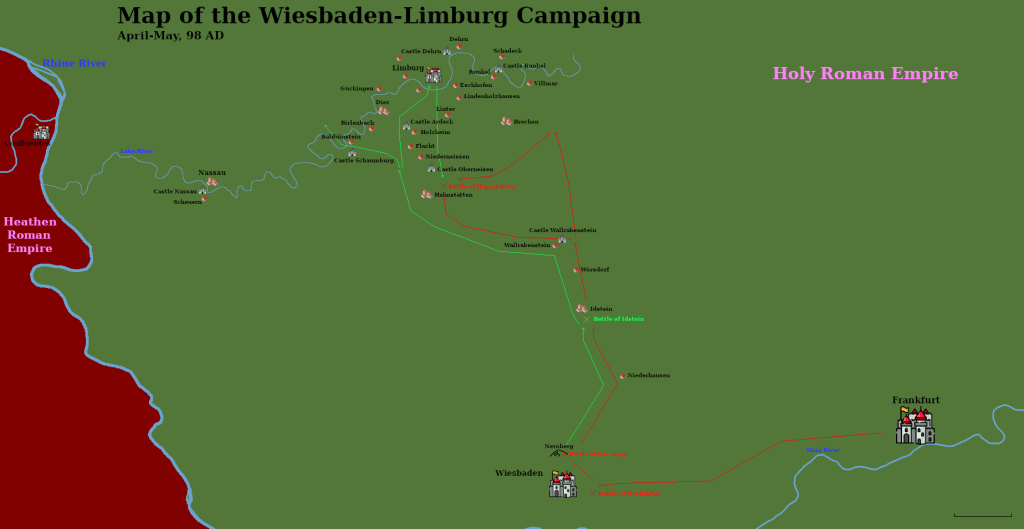

Trajan Augustus, meanwhile, is campaigning near Frankfurt, whose people have been a thorn in his side since the fall of Wiesbaden. As William began his campaign, another army gathered in Nassau also began campaigning. At the time, Nassau was co-ruled by the brothers Walram II and Otto I. Walram, as the elder brother, took primary command of the 10,000 men under their banner and began campaigning around Wiesbaden, which was to the rear of Trajan’s army, threatening to cut off his route back to Mogontiacum.

Trajan turns around and marches to meet the Counts of Nassau with 25,000 men. Understandably, the counts balk at the size of this force and manoeuvre around Trajan, fighting a series of skirmishes but refusing to give battle. Scouting parties from the two armies clash near Wiesbaden, and then atop a hill called Neroberg. The Rhinelanders give way and Trajan presses the advantage, pushing northward up to Idstein, where a skirmish is fought involving 1,000 men on each side. Nassau’s knights carry the day with a thunderous charge down the cobblestone streets and drive the Romans from the town. However, when Trajan arrives the next day with a larger force, the Rhinelanders withdraw without a fight.

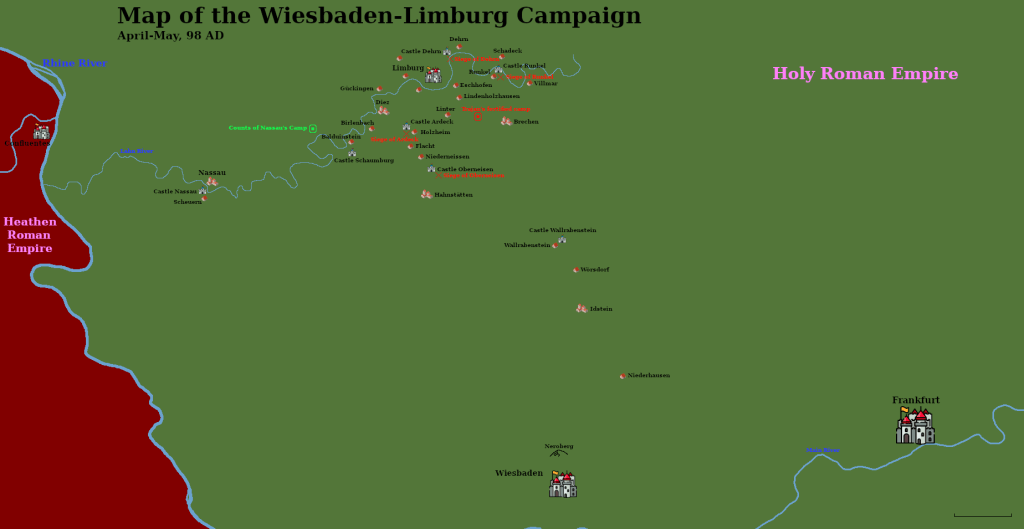

A larger battle is fought over the town of Limburg. Limburg is nominally ruled by the House of Dietz, and Count Gerhard III of Dietz refuses to abandon his town or his castles when called upon to do so by Walram and Otto. A portion of the army, some 3,000 men whose princes are upset that the army did not stand and fight at Idstein, stay in Limburg under Gerhard’s command. The remainder withdraw west toward Nassau. It is around now that Trajan receives word of the siege of Castle Reichenstein. He chooses to conclude his business with the Counts of Nassau first, since they stand directly on his path toward Reichenstein.

With this goal in mind, Trajan marches on Limburg. He finds a well-fortified zone around the town of Limburg, which lies along the Lahn River surrounded by villages and castles. There are not one, and not two, but six castles in the area, including the citadel within Limburg. Count Gerhard holds the nearby castles lightly while concentrating his men inside the walls of Limburg, intending to reinforce whichever castle Trajan attacks first. Trajan, however, splits his army in two. One force, consisting of only 4,000 men, approaches Castle Oberneisen from the south while the rest of his men move on Castle Runkel from the east.

Count Gerhard marches his army out to attack the southern column and engages it outside the village of Hahnstätten. He leads his knights in a charge that routes the Heathen cavalry, then tumbles their infantry to ruin, scattering them into the countryside. Trajan, however, still approaches from the east with the larger portion of the army. Gerhard’s knights, caught up in the excitement of the moment, forget everything in favour of chasing fleeing Heathens over hill and through field, but Trajan is not idle. While Gerhard is trying to rally his knights, Trajan’s men smash his infantry force from the flank, killing most and scattering the rest. Gerhard gathers up his knights and withdraws into Limburg, from which position he continues to direct the defence of the surrounding castles.

Now Trajan must invest the castles and simultaneously reduce the city of Limburg itself. He splits his army in three; two detachments lay siege to Castles Oberneisen and Runkel while the majority of the army build a fortified camp in a central location.

However, Walram and Otto are still active in the area. Having picked up survivors from the Battle of Hahnstätten, they now send parties to disrupt and skirmish with Trajan’s army. Every evening, they strike with lance and crossbow, destroying small parties and harrying outlying camps before disappearing into the gathering darkness before reinforcements can arrive.

A conundrum presents itself to Trajan Augustus. Laying siege is difficult with an enemy army harassing him, but he cannot pursue the Counts of Nassau because Limburg blocks the way. If he were to bypass the town, Gerhard’s knights would strike him in the back. He considers withdrawing back across the Rhine in order to relieve Castle Recheinstein via friendly territory, but he quickly discards this idea. That would be a journey of 100 miles and requires crossing the Rhine twice. Meanwhile, at Limburg, he is just 25 miles from Reichenstein.

Over the following three days, Trajan methodically breaks down Oberneisen and Runkel before moving on to besiege Castles Ardeck and Dehrn. The two are both owned by Count Gerhard himself, who remains holed up in Limburg, feeling the noose slowly tightening around his neck. It takes a full week to capture Ardeck and Dehrn. Trajan moves on Castle Schaumburg next, but the garrison abandons it and joins up with the Counts of Nassau, who are encamped on the other side of the Lahn River. At last, Trajan is able to lay siege to Limburg itself.

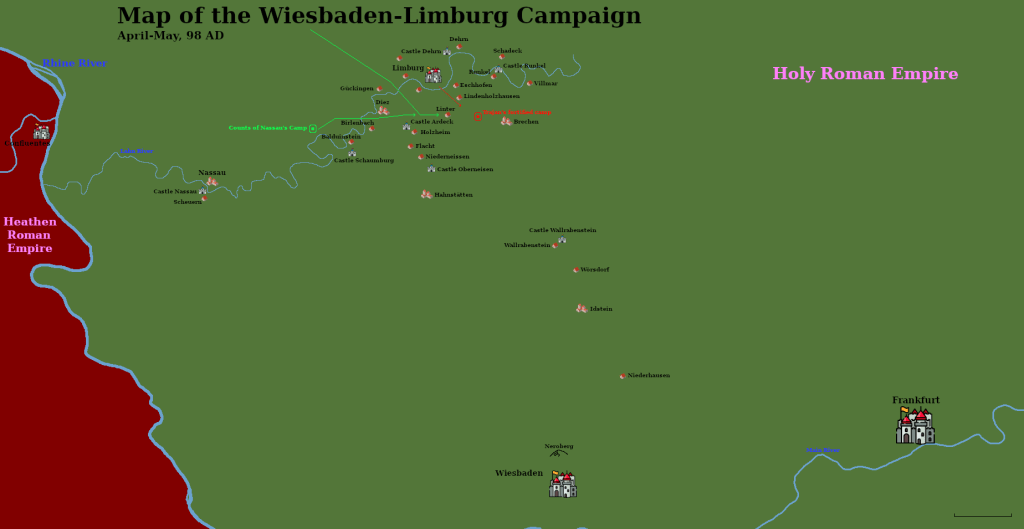

But now the situation changes. Now, Trajan, look to the northwestern horizon; look and behold the banner of William of Holland come into focus. William has left behind half his force at Castle Reichenstein while he has travelled here himself to relieve Limburg. Indeed, for the past ten days, both Count Gerhard and the Counts of Nassau have been sending letters begging William to come and rescue them. His prolonged siege of Reichenstein kept him busy, but now he sets aside that distraction and comes to the salvation of the houses of Nassau and Dietz. His 12,000 men join with Nassau’s 7,000, forming an army that is slightly outnumbered by the 21,000 Trajan Augustus has on hand after the casualties suffered at Hahnstätten and in capturing the castles. Trajan withdraws across the Lahn River to a nearby village called Linter, where he makes his stand.

Now Trajan has options. He can withdraw inside his fortified camp, but that would surrender the initiative to the enemy. He could pull up the sharpened stakes around his camp and deploy them in front of his army to make enemy cavalry’s charge more difficult—but that would imply that Trajan intends to stand still and receive the enemy’s charge. And Rome does not receive enemy charges; she pushes forward and attacks, attacks, attacks! The quickest way to the enemy’s rear, after all, is through his centre.

Oh Trajan, you do not yet realise what position Rome finds herself in. You have not closely examined or fully thought through what differences there are between you and this new enemy. You have not grasped the truth that your Rome may be an empire of iron, but the Romans who come against you now are from an empire of steel.

Forward march the legions of Rome. Upraise the shields, take the enemy’s missiles on its face instead of your own. Hurl javelins, then press the attack! Push in close, ward off their spears and strike with gladius. Thrust and stab, your arm may ache, but do not let up!

Down comes the guisarmes on your head, on your shoulders, and your unprotected arms. Now come the crossbowmen around the flanks. Feel the bodkin tips penetrate your armour. But the worst is yet to come. Look to the banners. See the knights proudly perched upon their stoic steeds, their bodies bedecked in steely circles of mail masking. Away flee the Roman horsemen; citizen and auxiliary alike, they run for their own salvation—and to your demise. Knights in polished armour with lance tips gleaming in the sun turn on you; with lances lowered, they charge. Horses’ hooves beating soil, a pounding in your chest, a thunder in your mind.

Romans break and flee through field and under leafy canopy, they run to save their lives; they run to escape the men of steel. Trajan runs too, and barely escapes with his life. He makes it back to the Roman side of the Rhine. Over the next few days, the remains of his army will follow. All told, only 1,000 men will return; 20,000 men are dead or captured.

Word of the great victory over the Heathens at the Battle of Linter spreads all across Holy Roman lands like wildfire. All the people praise God and William of Holland; even those who were skeptical before, now can do nothing but believe that the world has changed around them. Captured Roman battle standards are brought to Castle Reichenstein as proof of the the victory and to demoralise the defenders. Tribune Nepos agrees their situation is hopeless. He surrenders and the the Holy Romans allow him and his men to withdraw, along with the robber-knight who had been in control of the castle.

With the Heathens back on their side of the river, William’s Crusade has been a success. It’s over. Knights pack up their things and go home; princes gather up their men and march back to their castles. William of Holland urges them not to go; he begs and pleads, insisting that the war must be taken across the Rhine—the advantage gained by this victory must not be allowed to go to waste; the enemy must not be allowed to recover from his wound. But few listen to him. They look to their own matters. William is left almost on his own to stand on the banks of the Rhine and look across it with dreams in mind and ambition in his chest.

[Next]

Credits: All of the city, village, and castle icons in the maps are from Freepik (www.freepik.com). Everything else is my own.

Castle icon by Freepik

City icon by Icons Ideal

Town and village house icons are both by Ilya Kalinin

Leave a comment