The Roman Empire—But Also Medieval Europe

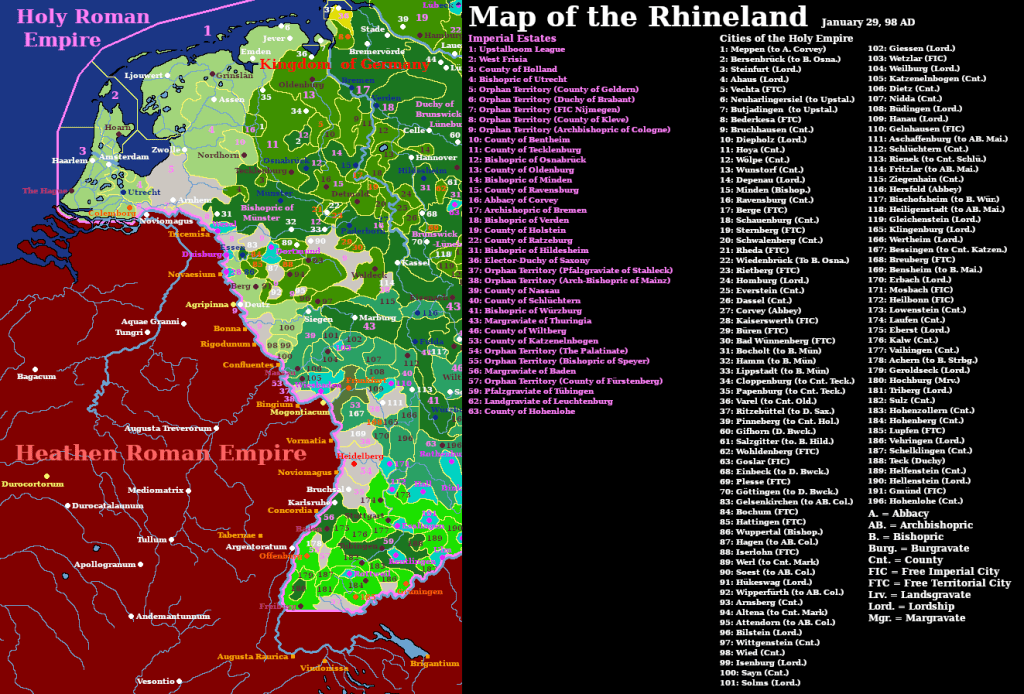

It is summer, 99 AD. It has taken time for the Holy Roman Empire to get its business in order, but things are beginning to settle down. There remain two emperors-elect, neither of them crowned by a pope: William of Holland reigns from the County of Holland and enjoys the support of the Rhineland princes from Utrecht to Freiburg, while Wenceslaus I of Bohemia enjoys the support of the rest of the princes. Wenceslaus would like to march his army west to deal with False Emperor William, but he cannot move against William directly while the latter is still riding high on the popularity bought by his resounding victory over the Heathen Romans in the Battle of Linter. Many princes who support Wenceslaus are, nevertheless, sympathetic to the man from Holland who crushed the hated heathens and may switch sides if so pious a man were attacked unprovoked by the king of Bohemia. Wenceslaus contents himself with supporting the Frisians and goading them into attacking Holland; Since the Frisians have long-standing beef with William this is nothing new, and since no Frisian lays claim to the same title William does, it is not seen as base bickering as it would be if Wenceslaus were to attack William directly. However, this avenue of attack is closed off when William, joining forces with Bishop Otto II of Münster, defeats the Frisians near the West Frisian capital of Hoarn and forces their capitulation.

William, however, sees all this as a distraction. Rather than utterly crushing the West Frisians, he announces that Christians ought not be killing one another when so foul a foe is so near at hand as the Heathen Romans. The forces of Hell are at the very gates of Christendom and yet the Christians squabble among themselves rather than uniting for the cause of Christ. He calls for a renewed crusade to take the fight directly to the Heathens on their side of the Rhine. The bishops of Münster, Utrecht, and Osnabrück enthusiastically agree. Over the course of the fall and winter of 99-100 AD, the bishops go on preaching tours all over the northwestern part of the Holy Roman Empire. Their preaching inspires other bishops, priests, and even laymen to go on similar tours to rile up the princes, the knights, and the masses alike and stir them to action. By the time winter turns to spring, thousands of men have streamed into the Hague, where William holds court barely more than a stone-throw away from the Rhine. Thousands more stream into Limburg to follow Count Gerhard III of Dietz, whose courage in the last campaign has inspired many. Others go to Münster to join Bishop Otto II’s army. William collects 16,000 men, while Bishop Otto gathers 11,000, and Count Gerhard gets 8,000. Smaller armies rally around Counts Walram II and Otto I of Nassau, Count Adolf VII of Berg, Pfalzgrave Hugo IV of Tübingen, and the free territorial city of Freiburg.

Meanwhile, Trajan Augustus has only briefly visited Rome once in 99 AD, and has otherwise spent almost all his time bouncing around the Rhine and Danube frontiers shoring up the defences. He had intended to launch a campaign into Holy Roman territory in the summer of 99, but was compelled by Sartaq and Nogai’s raids to visit the lower Danube instead to reinforce that frontier and oversee the rebuilding of defences there.

The great throngs attracted by the preaching of Bishop Otto and others do not go unnoticed on the Heathen side of the Rhine. This religion is new to the Romans. Oh, they are familiar with Christianity, but the Christianity they know is small and divided into many sects which have vastly different theologies that range from those who follow the teachings of the Apostle Paul to the Gnostics, who reject the god of the Hebrew Bible as a cruel tyrant, to the Ebionites, who are effectively Jews who follow both the Law of Moses and the teachings of Christ, but do not worship him. Not all of them get along with each other, and none of them have ever declared anything like the holy war brewing among the new Christians across the Rhine.

In order to enforce unity and ensure no divided loyalties exist among his own troops, Trajan takes steps to purge his ranks of any Christians who might become a fifth column. Returning to the Rhine frontier and taking up residence in Augusta Treverorum, Trajan issues a decree requiring all Rhine garrison soldiers to attend sacrifices to the gods of Rome, including deified rulers of the past such as Julius Caesar and Augustus. Those who will not attend or will not do proper obeisance to the gods are declared to be ‘atheist’ traitors and are given the honour of being crucified in imitation of their dead god—yes, dead; Trajan repudiates the resurrection story and insists that Christ is a dead god who shall never return. Trajan goes on to persecute civilian Christians as well, ruthlessly driving the ‘atheists’ out of all the forts and cities along the Rhine. News of this persecution travels with the Christians who flee from it and seek refuge among their co-religionists in Holy Roman lands, and it pours fuel on the already-raging fires of crusader zeal.

It is almost spring, 100 AD. In total, about 47,000 men stand poised to launch a crusade across the Rhine River. Though theoretically led by William of Holland, in truth the Holy Romans are a coalition composed of many elements that can and will operate independently of any kind of centralised control. Arrayed against them are 60,000 men made up of elements of a dozen different legions and various auxiliary units. One leader commands all these forces: Trajan Augustus. One man has advantages not enjoyed by a dispersed command structure. He can set a unified strategy, focus all his forces on a single goal, and is a great force multiplier on the field if his men have confidence in his abilities. However, one man can only be in one place at one time.

It is now April, 100 AD. All up and down the Rhine River, armies of the most zealous German and Dutch Christians are crossing the river with weapons in hand, intent upon punishing the Heathens who invaded their last the year before last. For his part, Trajan Augustus has expected this crusade to come. All the fiery preaching by Bishop Otto II of Münster has not gone unnoticed on the other side of the river. Trajan figures that if he kills Otto, the crusading snake’s head with be removed and the others will scurry back across the river. The only problem is that he doesn’t know where Bishop Otto is. By now, Trajan is beginning to get a sense of the lay of the land across the Rhine, but he only has a vague idea of where Münster is. He does, however, know where the Hague is and that William of Holland holds court there, so when a 16,000-man army crosses the Rhine from the direction of the Hague, Trajan has good reason to believe that’s where the man claiming to be King of the Romans is. And any man claiming such a title must be brought low.

William crosses the Rhine near where the Dutch city of Nijmegen used to be, which is now the Heathen Roman settlement of Batavorum. He immediately finds a series of forts blocking his way. Batavorum itself is a large walled town with a strong legionary presence, while a string of small forts keep watch over the river. Most such forts are rather humble structures with small garrisons. William easily breaks through them and lays siege to Batavorum itself, but not before the defenders sent a messenger to appraise Trajan of the situation.

Trajan Augustus is over 170 miles away by road, residing in Augusta Treverorum (which the Germans know as Trier) with 28,000 men. It takes three days for the message to arrive. As soon as he hears word of Batavorum’s predicament, Trajan orders his army to move out. It takes a day for such a large army to get moving and, optimistically, it might take ten days to reach Batavorum.

In the meantime, William looks up at the walls standing over him. They are made of stone and stand atop an earthen embankment. Heathen soldiers look down at him through crenellations and from towers. William takes this all in and he is not at all impressed. After all, the towers are inset inside the walls rather than protruding from them, preventing soldiers in the towers from shooting attackers at the base of the wall. Furthermore, the battlements don’t overhang the base of the wall and they have no machicolations, which means that in order to shoot attackers down there, the defenders have to lean out through the crenellations, exposing themselves for all the world to shoot at. To the Medieval eye, this so-called fortress is really quite primitive. And that’s to be expected; the Heathen Romans could build better fortifications, but this forts are not meant to withstand a lengthy siege by experts in siegecraft like the Holy Romans, they’re meant as a springboard to launch operations across the Rhine against Germanic tribes whose skill at siegecraft is underwhelming, to say the least.

In a mere four days, William has seized Batavorum by storm; two days later, he marches along the Heathens’ own road to Tricemisa, which he reaches in two days and besieges. Tricemisa’s defenders know that Trajan Augustus is already on the way, and William has heard this as well. Neither of them know just how close he is, but the defenders believe they can hold out until he arrives. Once again, however, Christian siegecraft of the mid-13th century easily crushes Heathen fortifications from the twilight of the 1st century; in only two days, William’s crusaders break through the defences and destroys the garrison. Most are killed, but some surrender.

And now begins a trend that will only grow stronger over time. Surrendered foes are put in chains. As the town attached to the fort is plundered, William’s men seize all the civilians they can get their hands on and put them in chains as well. Merchants have come with the army to sell it supplies and buy booty captured in victory; part and parcel of the booty they intend to purchase are long lines of Heathen men, women, and children chained together and carried off into Christian lands. This is the perfect opportunity for evangelism, say the priests; what better way to share the love of Christ than to purchase persons to preach to while working for the greater good of God’s Kingdom?

We must turn back to the matter at hand however, for as the purveyors of human goods return across the Rhine with their living property, William’s men encounter scouts from Trajan’s army. Trajan has force-marched his men since hearing of the fall of Batavorum and arrives presently. Near a fort called Asciburgium, about of a third of the way from Tricemisa to Novaesium, a foraging party of William’s men are killed by Trajan’s scouts, but a group of William’s men-at-arms arrive and drive away the scouts, only to be attacked by a block of legionaries, who are subsequently scattered by charging knights.

Both generals hear about this escalating battle as it is underway and scramble to feed men into the fight. Men run on foot and horseback, arriving piecemeal and sometimes without having donned their full kit of armour. Groups of soldiers from the two sides stumble over each other on their way to the battle, breaking into maddened melees metastasising into a frantic front staggered across a line from the forest west of the Roman highway all the way to banks of the Rhine, a miles-long encounter zone. In this kind of battle, the training and organisation of the Heathen Romans shows. Led by centurions, tribunes, and veteran soldiers, small groups of Heathens stay together in unmoveable blocks with shields facing every direction.

Holy Romans, by contrast, run to and fro individually or in clumps. In an army made up of feudal retinues, no one seems to know what the chain of command is when confusion set in. Two groups coming together argue over who should submit to the other’s authority instead of simply following a clear, pre-established chain of command. Organisation breaks down completely on William’s side. Even as William rides around on his horse trying to restore order, the knights and princes who follow him keep on bickering. Meanwhile, Trajan Augustus brings up the last of his own men to leave their camp. Drawn up in a proper battle line, the the Heathen Romans smash the scattered clumps of Christian soldiers who do not immediately run at the sight of them.

Seeing this, William knows he has lost the battle. He takes what men he can gather and withdraws back to Tricemisa, and then across the Rhine.

Trajan has no time to rest his weary men, however, for word reaches him in the aftermath of the battle that another army has crossed the Rhine just behind him at Novaesium.

Bishop Otto of Münster has joined the fray a little later than he intended, but he is here. Otto has only 12,000 men and aims to link up with William of Holland, whom he believes to still be active in the area. Although he knows Trajan Augustus is nearby, he has no idea how close the Heathen emperor is, nor that William has already fled the theatre. What Otto does know is that a Heathen fortress stands before him with barely a skeleton crew defending it—Trajan took most of the garrison with him as he passed by Novaesium only a few days prior. Novaesium falls the day after Otto cross the Rhine, and it is burned to the ground, its population put in chains.

Trajan arrives as Otto is in the process of burning the city. Rather than leaping directly into the fight, Trajan encamps nearby. His men are exhausted from marching here and fighting a battle, so Trajan decides it best to give them at least a little rest before the next fight.

Otto is now trapped against the river. Crossing back now would be foolish, lest Trajan attack while Otto’s men are only halfway across. Although he is sorely outnumbered—12,000 to Trajan’s 27,000—the bishop decides he must make his stand. In the morning, he draws up his men inside a bend of the river, where Trajan will have difficulty bringing his superior numbers to bear. Dismounting, Otto’s knights fight on foot wrapped in mail from head to toe, and with kite shield and sword in hand. Bishop Otto himself dons a Righteous coat of plates and belt of Truth, puts on the helmet of Salvation, and picks up the shield of Faith and mace of the Spirit. Surrounded by his knights and zealous warrior-priests, the bishop performs mass on the field before the battle begins. A group of monks in armour with unsheathed swords parade a crucifix in front of the army while repeating the words of the liturgy spoken by Otto so that all can hear.

Words of the liturgy spoken in Ecclesiastical Latin drift across the field and are heard by the Heathens, who are unnerved by what they see and hear unfolding before them. However, Trajan reassures them by sacrificing a white bull to Jupiter and taking an augury. The augur tells Trajan that a great slaughter shall be had today, which the emperor chooses to interpret favourably.

Finally, the battle begins when the Heathen Romans let loose with their ballistae on Otto’s army. Otto’s men are unmoved, however, so Trajan’s army soon advances. Once they come in crossbow range, the Holy Romans pelt them with bolts and arrows. At last the armies clash, scutum on kite shield and gladius on arming sword. At first, Otto’s men refuse to give ground. Many Heathens fall; well-protected knights, better armoured than the legionaries and experts in combat, take their toll on the enemy. But most of Otto’s men are not knights; most are simple peasant levies, volunteers, and mercenaries. Most have, at best, a helmet, shield, and gambeson—a thick linen garment covering the body, arms, and thighs. These things provide limited protection from the Roman gladius. They are better armoured than the Germanic tribesmen the Romans are used to dealing with, but the average foot soldier of Otto’s army is not quite the match of the legionary. Even so, with their backs against the Rhine, they fight like lions. Eventually, Trajan’s army cuts its way through the peasant levies, breaking their lines and causing thousands to jump in the river in an attempt to swim across.

However, Bishop Otto remains in the thick of the fighting with his knights and battle-priests. Otto is the picture of righteous fury in his coat of plates with holy mace beating the wrath of God into the hordes of Hell. Though Satan’s servants encompass his small band they fight on. Knowing they will die does not disturb them, nor cause their arms to falter. It invigorates them to know they will perish in the Lord’s service, and so they fight on. For every one of Otto’s knights who fall, three or four Heathens must give their lives. Slowly, Otto’s men are whittled down until only the bishop remains. A dozen foemen fall to Otto’s zealous fury before a score of wounds collectively bring him low.

And so Bishop Otto was killed on a small piece of land surrounded by a bend in the Rhine River along with eight thousand of those who followed him. Of the remainder, most were captured. Only a handful made it across the Rhine.

All this was seen by the people of the Free City of Kaiserwerth, directly across the river from Novaesium, and the Kaiserwerthers would spread the tale of Otto the Martyr, slain by the Heathen Augustus.

[Next]

Leave a comment