4.1 – The Silver Syndicate (1570 – 1575)

The war that broke out between Spain and China in 1570 is known by several names. Spaniards call it the China War while the Chinese call it the Dongdu War (named for Tondo, which is called Dongdu in Chinese). History calls it the Sino-Spanish War. It was a long and intermittent conflict that took place mainly on the seas between China and the Philippines with occasional Chinese forays on the Philippine island of Luzon and Spanish incursions into the Chinese provinces of Guangdong and Fujian.

In Xinguo, the conflict that broke out is called the Warehouse War for reasons that will become obvious. The war didn’t have any immediate effects on Xin-Mei relations because it took time for Mexico City to even find out they were at war with China, and it took even longer to decide what that meant for their relationship with Xinguo. A couple of viceroys had come and gone since Antionio de Mendoza’s time, but in 1570 the one to hold the office was Martin Enriquez de Almanza y Ulloa. Enriquez wrote to King Felipe II requesting instructions on how to handle the situation. Since 1543, Felipe II had governed Spain as regent in the name of his father Karl V, but Karl abdicated in 1556, leaving Felipe to succeed him as king. Felipe II decided what the war meant was that New Spain could no longer sell silver to Xinguan merchants. Silver exported to Xinguo would end up in China, and Felipe didn’t want to finance his own enemy’s war against him. Therefore, in March 1572 Viceroy Enriquez banned trade with Xinguo entirely.

Given the challenges facing Xinguo that we described at the end of the last chapter, it was a bad time for Spain to be cutting off the silver flow. It was quite simply unacceptable. Good thing for Bai Guguan he didn’t have to accept it.

Since the mid-1550s, Spanish merchants had been permitted into the Dongguang Silver Society at Bai’s behest, which allowed them to trade directly with the Treasure Fleet stopping in Ningbo every year, usually in July or August. This had given rise to a cabal of Spanish merchants who controlled trade between Spain and Xinguo within Xinguo’s borders. Some were based in Lima, Peru, but the majority were in Acapulco, Mexico. These two groups are known collectively as the Silver Syndicate, an organisation which officially didn’t exist. It was a highly exclusive club, permitting entry based mostly on personal connections, and since it was so influential in the DSS, the syndicate could prevent other Spanish merchants from obtaining DSS membership. Thus, only members of the Silver Syndicate could do business with the Treasure Fleet, and by extension only they could do business in Xinguo at all. Any other Europeans who tried would come under attack from local gangs and would find the authorities to be unsympathetic at best.

Felipe II’s embargo of Xinguo, therefore, had no discernible effect. Silver Syndicate merchants bribed the right people and carried on with business as normal. In 1574, they even managed to wrangle their way into gaining memberships in the Ningbo Silver Society and got the ban on foreigners staying the night in Ningbo lifted. They accomplished this by loaning Wei Yonglong enough money to finance a major incursion into the Pit River country and gaining political favours in return. Even so, Wei Yonglong still refused to allow foreigners to buy land inside the city walls, so the warehouse in Dongguang remained the centre of the operation.

Viceroy Enriquez, however, wasn’t going to put up with this forever. The Silver Syndicate would have to be dealt with.

Now, with everything said about the Silver Syndicate so far, it’s necessary to clarify one vital point. As successful as they’d been at seizing control of the Spain-Xinguo trade within Xinguo, their influence within New Spain and Peru was limited. Members, wealthy as they were becoming, were still up-and-coming members of Spanish colonial society. When they gained membership in the DSS, they’d been an eclectic bunch of opportunistic merchants with little else to their names. Their scheme had gained them each a decent-sized fortune, but they were far from being wealthy enough to have attained immunity from the law.

So it was that in June 1575, the members of the Silver Syndicate gathered in Acapulco and made preparations to travel to Xinguo to meet the Treasure Fleet. Most of them were staying in the villa of Diego Perez y Gomez, one of the founding members of the syndicate, who owned an estate near Acapulco. Viceroy Enriquez personally showed up at the villa during supper one evening with a small army of 300 men and surrounded the building. He placed them all under arrest. Only the Peruvian members of the syndicate remained, apart from a handful of Mexican members who escaped arrest and went into hiding. All of them were minor players compared to those now in custody. Thus, in one fell swoop, Enriquez had decapitated the serpent.

That wasn’t enough for him, however. In time the syndicate might re-emerge, and Enriquez suspected the Peruvian viceroy to be in their pocket. He wanted to send a message, both to the syndicate members who remained at large and to the Xinguans. To that end, he made Diego Perez y Gomez an offer. Perez had a son and two nephews whom he’d brought into the syndicate, as well as a brother who was also a founding member. The son and nephews were in custody while the brother remained at large. Enriquez could put them all away for a long time, but he assured Perez that he’d much rather give them all pardons. All he required in return was for Perez to perform a little community service in the name of New Spain.

On July 5th, 1575, Diego Perez y Gomez set sail from Acapulco, bound for Dongguang with a cargo full of heavy crates. The crew wasn’t told what was in them, but they assumed it to be the usual: silver, cocoa, spices, and the like. After all, the crates were in fact labelled as such. When they arrived on July 13th, the people in Dongguang were surprised they’d come so early. The Treasure Fleet didn’t normally arrive until late July or August. Nevertheless he was here, so the warehouse workers helped unload the cargo and stack it in the warehouse. The warehouse manager, who was a Xinguan in the employ of the Spaniards, organised the crates according to their labels, all under the watchful eye of Perez himself. When they were done, Perez congratulated the the warehouse staff, gave each of them several silver coins, and told them to take the afternoon off. All of them, including the manager, were bewildered by this reaction to a rather normal day’s work, but they headed over to the nearby pub without complaint. As the warehouse manager was leaving, Perez gave him a letter and told him to give it to the governor the next morning.

Meanwhile, Perez ordered his own crew back to the ship and prepare to set sail as quickly as possible. Once they were ready, Perez and a few picked men went back into the warehouse where they opened one of the crates. Most were full of gunpowder, with only a few crates of cocoa to cover for the rest, in case they’d been stopped for an inspection on the way here. Perez and his men set a long fuse and lit it. Wasting no time, they ran back to the ship and set sail. An hour later, Perez and his ship were well on their way downriver toward the Bay when the warehouse exploded.

As the warehouse manager stared at the smouldering ruins in shock, he remembered the letter he’d been given. He took it out, broke the seal, and read it. In both Spanish and Chinese, it announced:

“From Viceroy Martin Enriquez de Almanza y Ulloa to South Province Governor Bai Guguan and North Province Governor Wei Yonglong. Gentlemen, it is my sad duty to remind you that our mother nations, Spain and China, are at war. In light of this state of affairs, it must be declared explicitly that the relationship between New Spain and the Xinguan provinces may, therefore, be stated in a single word: war.”

And so began the Warehouse War.

4.2 – The Acapulco Armada (1575 – 1576)

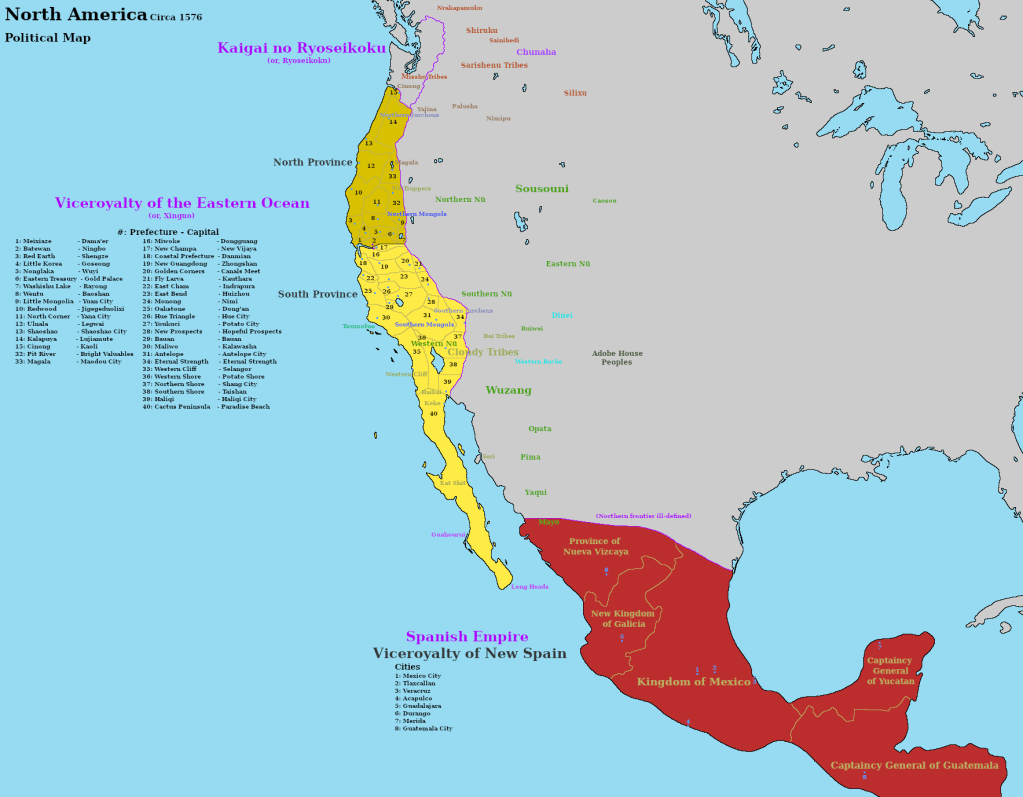

Simplified map of Xinguo in 1576 with prefectures and capitals:

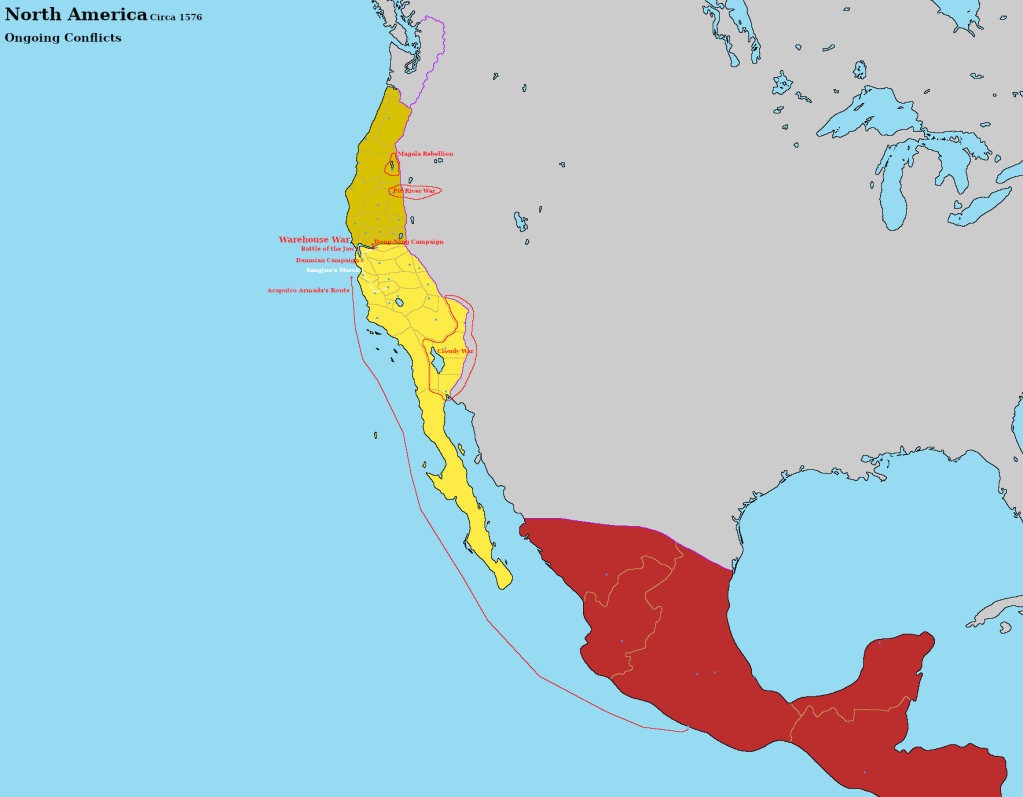

Simplified map of the ongoing conflicts in Xinguo in 1576

In the 1570s, Spain kept expanding its holdings in the Philippines despite intense resistance by China, Japanese and Chinese pirates, Portugal, and some native Filipino states. Other Filipino states actually supported them because of Spain’s successful use of the same carrot and stick system they used in the Americas. Filipinos could have positions of power within the new Spanish system and intermarry with Spaniards if they worked with Spain instead of against it or trying to remain neutral.

Their hold, however, was precarious. Many Spaniards suggested they abandon the Philippines and conquer China instead. China, they claimed, was vast and wealthy, but also extremely weak and would be easy to conquer. While they weren’t entirely wrong about China’s weakness, they underestimated the sheer size of the place and the difficulty of maintaining any meaningful control of it outside the major population centres. King Felipe II never took any of these suggestions very seriously since he already had enough to keep him busy. Spanish conquest of the New World was still underway, and Spain was also a key player in the incessant wars being fought in Europe.

Xinguo, however, was a different matter. Compared to China, it was sparsely populated and didn’t have thousands of years of history rooting it in place. If Spain invaded China, the vastness of the country alone could swallow Spain whole, but Xinguo had the potential to become intertwined with Spain through intermarriage and assimilation, just as Spain was doing to Mexico at the very same time. To top it off, Xinguo was politically divided, its standing military was small, and it’d take at least six months for reinforcements to come from China. From the outside looking in, it seemed Xinguo was ripe for the picking.

From the inside looking out, it was a slightly different story. The armies of North and South Provinces were tiny, it was true, but they didn’t need to be big because both provinces had a huge reserve pool of militia they could call upon. Besides the provincial militia (which was notionally over 60,000 men strong in each province), there were also magnates with their own armed guards as well as hundreds of local self-defence leagues. All in all, the two provinces probably had around 300,000 armed men each: the problem would be getting a sizeable chunk of that number together in one place under a unified command structure which could march them all in the same direction at once.

Their navies were weak, but were rapidly growing stronger: the Nine Anti-Piracy Expeditions had taught the Xinguans they needed a better navy and so they’d hired Korean shipwrights to design and build whole new fleets of Korean-style anti-pirate castle-ships and turtle-ships (although a lack of funds had stalled out the building of new ships much earlier than the governors had wanted).

A clever strategist might find a way to turn the two provinces against each other: however, while the Wei and Bai families had never seen eye to eye, they were also pragmatic enough to work together when it benefitted both of them to do so, as shown by the Treaty of the Two Governors signed by Wei Chengjia and Bai Guguan.

Nevertheless, Viceroy Enriquez requested and received permission from Felipe for an invasion of Xinguo in 1575—Felipe even promised to cover half the cost of the expedition from the royal treasury. Since it was already late in the year, he decided not to set out until the spring. Over the winter, he prepared an army of 8,000 men. Half of them were a mixture of Criollos (white persons of Iberian ancestry who were born in the New World) and Mestizos (people of mixed European and American heritage). The other half were recruited from New Spain’s indigenous population. Mexican Natives were rapidly diminishing in number and influence as a result of European diseases, which they had limited experience with as a result of contact with Xinguo. Still, far from falling into irrelevance, the Natives continued to be a major part of New Spain’s population. A fleet was made ready in Acapulco and supplies and money were stockpiled.

In June 1576, the expedition was ready to set sail under the command of a man named Alonso Flores de Salas y Vargas. The Flores family moved to New Spain in the 1520s and became one of the early families to settle in the Acapulco area. By virtue of being among the first there, the elder Flores became an important local landowner with several tenant farmers working his land in the area. Born in Acapulco in 1535, Alonso was present during the 1542 defence of the city against Lin Weishi’s invasion. His father served in the militia during the battle and was killed in the Camp Fight. His father’s death at the hands of the Chinese had a lasting impact on the boy. It was probably the impetus behind his pursuit of a career in the army as well as his desire to lead the invasion of Xinguo.

Flores was a decently successful man, all things considered. Wealthy enough to be considered affluent without being among the richest, and competent enough as an army officer to receive several commendations for his service without ever gaining true fame. Besides serving with distinction on the northern frontiers of New Spain, Flores managed to marry well by marrying Mayor Vazquez de Coronado y Estrada (born in 1546), daughter of the famous explorer Francisco Vazquez de Coronado and his wife Beatriz de Estrada, who was famous in her own right for her piety and charity.

Nevertheless, he lived largely in obscurity until the question of who should lead the Xinguo expedition came up. Competition over the position was fierce: being the first to conquer part of Xinguo would put a man in a position to take the biggest slice of the Xinguan pie for himself. All waged a campaign of slander agaisnt each other for months. It wasn’t until May 1576 that Viceroy Enriquez finally decided to go with the compromise candidate, Alonso Flores. Flores had thrown his hat in the ring without really expecting to actually be chosen, but he can’t have been unhappy with the result.

Flores was given a decently accurate and up-to-date map of the Bay area, and had also been given instructions on how to reach Dongguang, which amounted to roughly: “Entering the Bay, sail past the island into the next bay and follow that eastward. Keep to the south branch of the river and on its left bank you’ll come across the great walled city of Dongguang.” This wasn’t very helpful, considering there are two islands which one can sail around and reach two completely unconnected bays, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

There was a problem, however: the man he’d been assigned as a guide and interpreter disappeared the week before the expedition was set to leave. He’d been a member of the Silver Syndicate, and it seemed he didn’t want to aid in the conquest of his former trading partners. Flores informed Mexico City of the guide’s disappearance and in return received orders to delay departure until a replacement was found (whether or not one could be found wasn’t clear: most of the other Silver Syndicate members who’d been arrested had been banished to Spain).

However, delaying was something Flores really didn’t want to do, since he’d heard the viceroy was considering replacing him as commander. The day before departure was set to take place, a young Franciscan monk by the name of Benito Aguilar y Chavez de Sarria presented himself and volunteered as guide and interpreter. Aguilar had been part of a missionary venture to South Province in 1567, where they had attempted to set up a mission station. They were only there a few months before they were politely asked to leave—by the governor’s soldiers wearing full battle gear. He spoke Spanish and Nahuatl and claimed to have picked up conversational Yue during the mission’s short-lived existence.

Armed with a map and a guide, Flores saw no reason to back out now. Months of preparation had led up to this point, to delay now would be the height of embarrassment—and with the viceroy reconsidering the expedition’s leadership, there was no time to waste. On June 14th, 1576, the Acapulco Armada departed Acapulco with orders to seize Dongguang, capital of South Province. To ensure safe passage for follow-up expeditions, they were also to secure the towns and villages on the coasts of the Bay along the route to Dongguang. Capturing Bai Guguan was one of the secondary objectives.

The expedition consisted of the following:

Army: 8,000 soldiers

Tercio de Acapulco – 3,000 men

Cavalry – 1,000 men

Native Auxiliaries – 4,000 men

Artillery – 24 guns

Navy: 2,600 sailors

8 frigates

8 brigantines

20 transports

Total: 36 ships and 10,600 men

Included in the expedition was Juan de Oñate y Salazar, son of Cristobal de Oñate, hero of the Battle of Acapulco in 1548. Juan de Oñate would eventually become infamous in his own right for his role in the Acoma Massacre of 1599, but in 1576 he was still a young man looking to make a name for himself independent of his famous father.

There were no more merchants visiting Mexico and Peru from Xinguo, and with the Silver Syndicate beheaded only a handful of smugglers were still willing to make the trip from Spanish lands to Xinguo. As a result, the Xinguan provinces were completely unaware of the doom coming their way.

4.3 – The Jaw and the Teeth Forts (1576)

To reach Xinguo, Flores had to sail up the length of Long Peninsula, past the Silverway Coast, and past the Toumoluo lands. These places were thinly populated by Asian settlers at the time, so it wasn’t until the Acapulco Armada reached South Province’s coastal prefecture of Oaken Stone on June 19th that news of their approach began to spread.

Fishermen who spotted the armada reported it to the local garrison, who dispatched messengers who went by boat down the Oak River and up the Hue Canals to South River, and from there to Dongguang, where they informed Governor Bai Guguan of the armada’s approach. At first, Bai had a hard time believing such a large armada was already just off his coast, but other messengers soon began arriving from Tall Rock, Ruansen, and other coastal towns. On June 21st, Bai gave the order to muster the militia in all the coastal prefectures, including Miwoke Prefecture, which contained Dongguang, as well as New Champa. He expected to raise 20,000 men in the next fortnight, although most of them would be strung out along the coast.

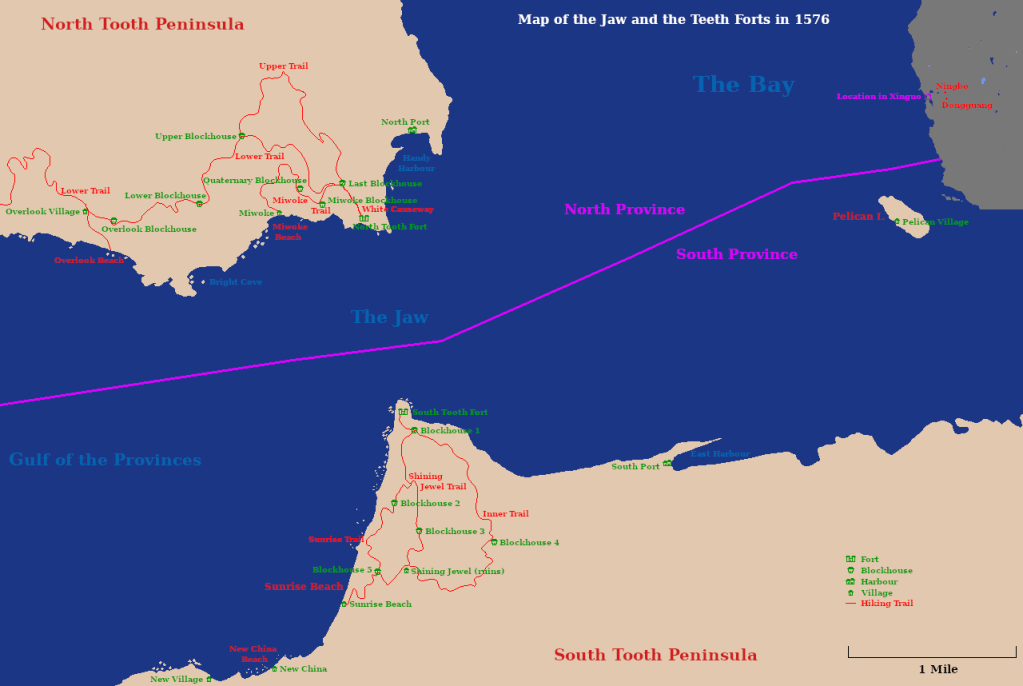

By that time, however, Flores had reached the Jaw. Actually, he reached it on June 20th, but sailed past it without seeing the entrance to the Bay since it was obscured by fog. Realising his mistake the next morning, he sailed back and paused to take in the view. Here, two peninsulas called the North Tooth and South Tooth come together and almost meet, forming the Jaw. The Jaw is a mile-wide strait connecting the Bay to the Gulf of the Provinces, which is the part of the Pacific Ocean at the border between the provinces. It’s the only direct water route from the ocean to Dongguang (the two indirect water routes are much longer and more arduous routes involving multiple rivers and canals, and it’s unclear whether the Spaniards were even aware of their existence at the time, much less knew how to navigate them).

Atop the heights overlooking the strait, Flores saw the Teeth Forts awaiting him. Now, these weren’t the sprawling fortifications that tower over the Jaw today: these were much smaller forts that’d been built during the Anti-Piracy War (1553 – 1569), when the Wokou pirates in the employ of Bai Guguan had turned on their employer after the Silver Wars. The forts had been a joint effort by Bai Guguan and then-North Province governor Wei Chengjia in a bid to keep the pirates out of the Bay. On the north side of the Jaw was the North Tooth Fort, which was held by northerners, and on the south side was the South Tooth Fort, garrisoned by Bai’s men. Situated on the heights overlooking the narrow strait of water below, any ship that sought to pass without the forts’ permission would have to run a gauntlet of withering cannon fire.

Each fort consisted of a rectangular curtain wall with rounded corners. They were made from rammed earth, which is a construction technique common to China that involves building forms and pouring dirt in, then tamping it down as tight as it would go. Pour more dirt in and tamp it down and keep repeating the process until you have a wall high enough for your purposes. Due to the way this method of construction works, the base of the wall was wider than the top, giving the the wall an inward curve that had the added benefit of deflecting cannonfire.

Gun emplacements faced outward in all directions, each fort armed with enough spaces for 40 artillery pieces. The majority of the guns pointed in the direction of the seaward approach with most of the rest pointing at the landward approach behind the forts.

In addition, the inside of the fort was dominated by a tower, also made of rammed earth, from which a cannon could be turned to point in any direction the defenders needed it to and fire over the walls at an approaching enemy. The tower also sported a flagpole, from which flew the plain red banner of South Province—or the plain black banner in the case of North Tooth Fort.

Besides the tower there were also a barracks, mess hall, and armoury, all of which were built like blockhouses and so could serve as a place to make a last stand if the walls were taken, although the defenders weren’t expected to hold out for long if that happened. Still, it was comforting for the men to have a place to retreat to. The geography of the place meant that there was only one way of getting to the forts: once under siege, the only way out for the garrison was over the cliffs.

Situated atop sea cliffs overlooking the strait, the forts were impossible to assault directly from the strait itself. Fortunately for an attacker, they didn’t need to do that, since there were a number of beautiful sandy beaches just down the coast from the forts on the outside of the Jaw that were perfect for landing troops and supplies on. North Tooth had one notable beach outside the Jaw, called Miwoke Beach. South Tooth had two: Sunrise Beach and New China Beach. The land rose sharply up toward the heights where the forts stood, but a number of hiking trails used by locals and tourists alike connected the beaches to the heights. This meant the best way for an attacker to take the forts was to land troops on the beaches, hike up the trails, and assault the forts from behind.

However, the builders not only accounted for this weakness, they’d planned the defences around it. Defences around the gates on the backside of the forts were well-prepared for an assault. All the earth used to build the walls and tower had to come from somewhere, and (in South Tooth Fort’s case) that somewhere was a series of two ditches on the landward side to make the approach harder. Just beyond the base of the walls was a swathe of wooden stakes, no more than a foot long, sharpened at both ends and driven into the ground. Not only that, but the hiking trails themselves were fortified with blockhouses. Blockhouses had a history in Xinguo stretching back to the early settlements of the 1440s, when the colonists needed cheap fortifications that could be thrown up quickly to defend against hostile natives.

The Teeth Forts’ blockhouses were of a typical style for Xinguo. They consisted of a square, two-storey house with the upper floor overhanging the main floor on all sides. Loopholes in the walls and in the floor of the second-storey enabled those inside to defend against attackers from any direction and even continue the fight from the second floor if the main floor was captured. Two ladders on the inside provided the only way from the main floor to the second floor. Stairs would’ve been more convenient to the garrison during peacetime, but it meant the enemy would have a harder time trying to fight their way up a ladder to get to the second floor. Each blockhouse was built to accommodate two squads of twelve men each, with food and ammunition to last for three days without resupply.

In addition to all this, each Tooth also had a lightly-fortified military harbour on the Bay side of the Jaw which hosted a garrison of warships to support the forts as needed.

It’s fair to say the Teeth Forts had done an excellent job keeping pirates out of the Bay. In fact, the forts had never fallen to the pirates, despite several attempts by the latter to capture them. 1569 had seen the last major pirate attack in Xinguo, during which the pirate leader had been killed. Immediately afterward, his followers fell into infighting, a situation Xinguo ruthlessly exploited so as to keep the pirates too busy fighting each other to raid Xinguo in force. With the pirate problem dealt with and no other seaborne enemies threatening Xinguo in the foreseeable future, it became hard to justify the expense of maintaining the Teeth Forts.

By 1576, cannons and personnel had repeatedly been stripped away in favour of other projects. What was left were skeleton crews who spent most of their time fishing and sea-gazing. In fact, the commander of North Tooth was away attending a beach party at a friend’s house when the Acapulco Armada arrived.

Having spotted the armada passing by the previous afternoon, the commander of South Tooth was slightly better prepared. His name was Huế Bảy Thắng, a cousin of Huế Thành Học, richest magnate of the Vietnamese colony of Hue and prefect of the Hue Triangle. Bảy Thắng used this family connection to secure himself a comfy job at the seaside where he could spend lots of time at the beach. Bảy Thắng was something of a slovenly fop. He spent as much time sailing his boat in the warm summer sun and hosting beach parties as he did on his duties as commander of the fort.

That being said, even he recognised the threat posed by a Meixigou invasion of Xinguo. After hearing about the destruction of the Spanish warehouse in Dongguang and declaration of war by Viceroy Enriquez, Bảy Thắng assumed steps would be taken to shore up defences around the Jaw, so he simply waited for something to happen. At the very least, he expected more soldiers, considering he was at less than half capacity with only 400 men. Weeks passed, and nothing was done. Eventually, he sent a request to Dongguang for orders, but the response was that he was simply to follow his standing orders to keep watch over the Jaw.

Slowly, it dawned on Bảy Thắng that if Enriquez had been serious and actually did send a fleet to attack the Jaw, Bảy Thắng and his men were completely on their own. Finally, at the beginning of June, he started making preparations on his own initiative. South Tooth Fort’s walls had been damaged by an earthquake in 1573, so he had them repaired, and he purchased large quantities of gunpowder, lead, and arrows to stockpile in the fort and the blockhouses. All was paid for out of his own pocket, since his budget for maintaining the fort was paltry. He even scavenged a few cannons from a ship that had run aground on New China Beach and been abandoned.

The commander also wrote to his cousin in Hue, impressing upon him the urgency of the situation. If Meixigou wasn’t making idle threats, they’d be sending some kind of expedition soon, and Xinguo needed to be ready. If Governer Bai Guguan wouldn’t take the threat seriously, then someone had to. Thành Học doesn’t appear to have taken the threat very seriously, but he did send 100 of his own men to reinforce Bảy Thắng. These were simple militia men, clad in padded armour and wielding swords, glaives, and fire lances. This brought the garrison up to 500, with 17 cannons, which was half the fort’s intended capacity of 1,000 men and 40 guns.

When the Spanish ships were spotted sailing on by, Bảy Thắng breathed a sigh of relief. To him, it seemed the threat had passed. Their goal hadn’t even been the Jaw to begin with. Now he could rest easy, send his cousin’s men home, and go back to his normal routine. Then the Spaniards returned the next morning. Time would tell if Bảy Thắng’s preparations would be enough.

4.4 – The Jaw: Battle of Blockhouse 1 (June 21, 1576)

Alonso Flores knew there was no time to waste. Surprise had been achieved (he hoped), but its effect wouldn’t last long. To seize the opportunity before it slipped away, he had to act quickly. Arriving late in the morning, Flores paused briefly to assess the situation and quickly identified Sunrise Beach as the place to land. He was under orders to seize both forts to secure a path through the Jaw, but had also been cautioned against attacking the northerners unprovoked. Viceroy Enriquez was hoping that the history of peaceful trade between New Spain and North Province would mean violence between the two could be avoided, so he told Flores that he should only attack the northerners if they refused to surrender the fort. South Province was to be offered no such deal. Flores decided to make an example of them instead.

The armada’s ships anchored offshore and launched boats full of men. Native auxiliaries landed first. Even at this late stage in the colonisation of Mexico, most were still armed with traditional weapons, since a Native auxiliary required special permission to wield a Spanish weapon. Clad in traditional padded armour and wielding bows and obsidian-studded clubs called macuahuitls, the auxiliaries fanned out to scout the surrounding area while the rest of the men and supplies landed. At the edge of Sunrise Beach was a village of the same name. Both were deserted except for one paraplegic old lady. Through several piratical assaults on the Jaw, the inhabitants had learned to evacuate quickly when they saw potentially hostile sails on the horizon.

Beyond the village, wooded hills arose. From the outskirts of the village, the auxiliaries could see both the fort on the heights and the blockhouses leading up to it, and they knew they were being watched by the men inside.

The Natives left the old lady to her own devices and returned to the beach, where the rest of the army was coming ashore. They were aided by the presence of a set of docks and boathouses along the waterfront. One of the boathouses was owned by Huế Bảy Thắng, which was where he kept his beloved sailboat.

Alonso Flores himself came ashore to lead the assault. Once a few hundred more men had come ashore, Flores decided it was time to make a push toward the fort. Artillery was being brought ashore when Flores gave the order to set out. Sword-and-buckler men advanced alongside arquebusiers and auxiliaries, 300 in all. Making their way uphill, they could see Blockhouse 5 ahead of them. Trees in the area around the blockhouse had been cut down to create a clear field of fire all around it.

Confident in his own superior numbers, Flores decided to waste no time in storming the blockhouse. Arquebusiers and archers stood at the ready to provide covering fire while the men with swords and macuahuitls prepared themselves. Shields raised, the men charged across the field as fast as their legs could carry them, ready for a hail of bullets and arrows to pour into them at any second. But none came. They set an explosive at the door, blew it off its hinges, and charged inside. No one was there. Blockhouse 5 had been abandoned.

This buoyed the morale of the men, who believed they must’ve taken the enemy completely off-guard. Flores was slightly less optimistic, but he didn’t want to slow down the advance now. Two more blockhouses lay ahead of him, so he split his forces in two, with half attacking each one.

As they advanced, they passed the ruins of a small settlement. This had been Shining Jewel, the first attempt at a permanent Chinese colony in Xinguo. Its life had been cut short in 1445 by an earthquake.

Blockhouses 2 and 3 were similarly abandoned, but they were not empty. Four swordsmen who burst into Blockhouse 2 stumbled over a tripwire that set off a mine. One man was killed and three wounded in the resulting explosion. Those who stormed Blockhouse 3 were more cautious, and thereby avoided setting off the mine they found.

Noon had come by now, and Flores’s men had yet to see a single enemy soldier except for some distant figures watching them from the northern shore. Some of his soldiers were beginning to wonder out loud if the southerners had abandoned the fort altogether at the mere sight of the armada. Flores cautioned them not to be so presumptuous.

Indeed, the Battle of the Jaw was about to begin. Just up the trail, the forested portion of the hill ended entirely. Beyond the tree line, sitting out on the open ground, was Blockhouse 1. Only about 1,000 feet further on were the walls of South Tooth Fort itself, so close the Mexicans could now see men on the walls watching them. It was here that the southerners would finally make a stand.

Being so close made Flores nervous. Once out in the open, they’d be in range of the fort’s guns. Ten cannons were visible, and it was safe to assume they were all loaded. To make matters worse, the singular door to the interior of Blockhouse 1 was facing toward the fort, meaning the Mexicans would have to go around the blockhouse to reach it, with no cover on the way.

To avoid taking fire from the fort, Flores ordered his men to advance as close to the blockhouse as possible so the fort’s gunners wouldn’t be able to target them without fear of hitting their own blockhouse. This meant having everyone charge the blockhouse from the same direction, which would allow those inside to concentrate their fire—if, indeed, it hadn’t been abandoned like the others, but Flores believed this one would be the exception.

As before, Flores sent his men ahead with swords and shields while the arquebusiers and archers held back, ready to provide covering fire. This time, rocket arrows screamed out of the second-storey loopholes as soon as they broke the tree line. The Mexicans opened up a withering fire on the loopholes, which did little to reduce the number of arrows raining down on the advancing swordsmen.

Inside Blockhouse 1 were six of Bảy Thắng’s Vietnamese militiamen, all of them on the second floor. Each man was armed with a sword, three grenades, and a hundred rocket arrows. Their orders were to expend all their ammunition and then escape, if possible, and make their way to the fort. Forty Mexicans charged at the blockhouse, but they withdrew under a storm of arrows. Moments later, another forty burst out of the tree line with shields raised, but they also quickly withdrew in the face of a hundred-arrow volley. A dozen bodies of the dead and wounded lay on the field.

Flores decided to change tactics. His artillery was still being hauled up the hill, so bombardment wasn’t an option yet. Simply blowing a hole in the wall would probably have taken more gunpowder than he had on hand, considering it was made of sturdy redwood timber. That didn’t mean he was out of options, however.

Sixty men advanced with swords and macuahuitls, but this time six of them were armed with pikes, and another twelve with arquebuses. Under a storm of rocket arrows, they charged up to the base of the blockhouse. To the end of each pike was fixed a grenade. Once they were close enough, the men lit the fuses and thrust the pikes up through the loopholes of the second storey. As they did so, six grenades were thrown out at them. The men rammed the butts of the pikes into the ground and scattered.

Six grenades exploded outside, scattering shrapnel but inflicting only a few flesh wounds on the Mexicans. Six grenades exploded inside, killing one of the Xinguans and wounding another while the rest leapt down the hatch to the main floor. Outside, the Mexican arquebusiers charged up to blockhouse and began firing inside through the loopholes, killing one of the defenders.

Meanwhile, forty Mexicans armed with swords and macuahuitls ran around the blockhouse to the door. They set an explosive and retreated while it exploded, knocking the door off its hinges.

Inside, the three Xinguans still standing looked at each other. Surrender was unlikely to be accepted at this point, and there was no way to escape. They nodded to each other, pulled out their remaining grenades, and lit the fuses as the door was blown off its hinges. Mexicans flooded the room with swords held high, but were met with the sight of three lit grenades being thrown in their faces. They tried to back out, but immediately ran into more Mexicans charging in behind them.

Congested, the Mexicans now panicked. One was thinking clearly enough to snatch a grenade and toss it out a loohole. Another man threw himself on top of a second grenade, shielding his comrades from the blast with his own flesh when it exploded. The third grenade killed one man outright and wounded several others. Meanwhile, the three Xinguo-Vietnamese threw themselves on the floor at the other side of the room, thereby evading any serious injuries. Once it was over they leapt to their feet and drew their swords. One was shot by an arquebusier while the other two charged at the door, where they were quickly cut down.

It was over. Blockhouse 1 was in Mexican hands. Forty Mexicans had been killed or wounded, although half of those would recover in the next few days. Five of the six Xinguans were dead, with the sole survivor being taken into custody.

When the Mexicans saw there had only been six men inside the blockhouse they were shocked at how much damage they’d been able to inflict. Surprise quickly turned to anger, and they now looked up at the walls of South Tooth Fort with revenge on their minds.

4.5 – The Jaw: The Battle Begins (June 22, 1576)

The remainder of June 21st was taken up with troop movements. The rest of the army landed on Sunrise Beach and unloaded their supplies. Meanwhile, Alonso Flores sent men to occupy Blockhouse 4. 1,000 men went to besiege South Port, the harbour about a mile and a quarter from South Tooth Fort where the fort’s naval contingent was garrisoned. In better times, South Port might’ve harboured a dozen war junks built in the Chinese style. These days, there were two small, 10-gun coastal patrol vessels and one larger 28-gun turtle-ship of Korean design. Without the ships there, 1,000 Mexican soldiers could’ve overtaken the port’s meagre defences easily, but with the ships pointing their guns up the hill, the Mexicans decided to keep their distance. Another 1,000 cavalrymen were sent to scout the surrounding area and forage for supplies. That left 6,000 men and a battery of 24 artillery pieces to besiege South Tooth Fort itself.

At 6 AM on June 22nd, 1576, Alonso Flores approached the walls of the fort with the Franciscan monk Benito Aguilar and a soldier carrying a white flag. Aguilar addressed the Xinguan soldiers on the wall in Nahuatl, asking to see their leader. Nobody in the fort spoke Nahuatl, but they called for Bảy Thắng anyway. After listening to Aguilar translating Flores’s demand for surrender, Bảy Thắng replied in Vietnamese that he didn’t have a clue what Aguilar was saying.

Aguilar switched to Yue and managed to convey the concept of surrender before his modest vocabulary in that language was exhausted. Bảy Thắng, being a descendant of Vietnamese settlers, didn’t speak Yue either. He did, however, speak Jun, which was a composite language made up of a base of Mandarin combined with elements of other languages that served as the lingua franca of the Ming army, and therefore of the Xinguan army as well. His Yue-speaking soldiers were thus able to translate Aguilar’s words into Jun for him. As vague as Aguilar had been, it didn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out what the Mexicans wanted, but Bảy Thắng had no intention of giving it to them. He turned his eyes toward Sunrise Beach and replied in Jun, which was translated into Yue for Aguilar:

“A man must defend the honour of that which is his.”

With that, Bảy Thắng turned and walked away. This rather vague answer has puzzled those who study the event ever since. Naturally, the Mexicans assumed he meant to express his dedication to duty, honour, and the defence of his homeland, and the majority of historians think so as well. Others, however, have suggested that in that moment, his thoughts drifted to his beloved sailboat, which was currently behind enemy lines.

Regardless, the question of surrender was settled. Now there was nothing left but to fight.

Bảy Thắng had 494 men and 17 guns to defend the fort with. Most were militia with limited training and little, if any, combat experience. There were also 500 civilians in the fort with him: a mix of soldiers’ families and private contractors who worked for the army. Alonso Flores had 6,000 men besieging the fort, including 2,500 men of the Acapulco Tercio, who were not only trained in the ways of one of Europe’s greatest military powers, but many had experience fighting the Chichmeca or against other Natives on the northern frontiers of Mexico. On top of that, the South Tooth Fort’s defences were hilariously under-developed compared to the sprawling star forts of Europe that the Spanish army was used to dealing with. Granted, this army was mostly composed of Mexicans who’d never been to Europe, but they still had access to training manuals detailing how to capture forts that far outstripped South Tooth in defensive depth.

Flores’s army was lined up at the tree line behind a wall of their own which they’d constructed using gabions, which were large baskets filled with sand commonly used as a temporary fortification back in Europe. As soon as Flores returned to his own lines, Bảy Thắng gave the order to open fire, and before the cannonballs struck his lines, Flores gave the order to return fire. Thus began an artillery duel that would last for the next six hours.

Meanwhile, the navies of the two sides stirred. Before Flores’s troops arrived, Bảy Thắng had given the order for South Port to be abandoned and for the three ships to come to the fort’s aid if the Spanish ships approached the Jaw. In command of the three ships was a man named Fan Wenmin, son of Fan Dacheng, who commanded Chinese naval forces at the Battle of Acapulco in 1548. After two decades as commander of the Treasure Fleet’s naval escort, Dacheng had decided to make Xinguo his permanent home and got his son a job with the Xinguan navy.

Fan Wenmin sent one of his smaller ships to keep watch on the Jaw with her flag lowered. If she spotted Spanish ships approaching the Jaw, she was to raise her flag. In the meantime, Fan’s men abandonded the port, taking all the valuables aboard his two remaining ships and preparing to burn the port to the ground while sending the civilians away on foot toward the nearest village on the inside of the Jaw.

On June 21st, while the Spanish soldiers were making their way up the hiking trail, Bảy Thắng had sent a messenger to North Tooth Fort asking them for their support. The messenger returned with the reply that the commander of the fort was currently indisposed (he was still at his friend’s beach party, but the North Tooth garrison wasn’t going to admit that) and the second-in-command was unwilling to make a move without his authorisation. On June 22, Fan Wenmin sent another messenger directly to North Port, asking the naval commander there to send his ships in support of Wenmin’s ships, but the commander refused to moved without orders. Fan Wenmin would be on his own with three warships against the Spanish 16.

Outside the Jaw, Flores’s ships were under the command of Marco Melendez y Vargas, son of Flores’s mother’s sister. He’d been ordered to move his warships into the strait once he heard the sound of cannonfire, and bombard the fort. When Bảy Thắng began bombarding Flores’s position, Melendez moved out with 6 frigates and 4 brigantines. He left his remaining 2 frigates and 4 brigantines behind to guard Sunrise Beach and the transports. With only three ships in South Port, Melendez figured the rest of the Xinguan navy must be somewhere close by and suspected they would pounce on his ships the first chance they got. Unbeknownst to him, the bulk of South Province’s navy was stationed along the Red Rock River supporting the colonisation efforts there by denying river access to hostile Natives and bombarding the shoreline where necessary. They were much too far away to intervene.

As Melendez moved around South Tooth Peninsula, he came into view of Fan Wenmin’s scout ship, who hoisted her flag. Seeing this, Fan instantly ordered his men to set fire to South Port and board the ships, which they did. In minutes, he was on his way to join his scout ship, and then the three of them sailed for the Jaw. The 1,000 Mexicans sent to besiege South Port, watching all this unfold, decided to rejoin Flores.

The ongoing artillery duel between Bảy Thắng and Flores thus gained two new participants. While Flores fired uphill at Bảy Thắng, Bảy Thắng had to return fire while also firing on Melendez and his warships in the strait, who had to split their attention between the fort and Fan Wenmin.

Melendez decided he didn’t like taking fire from two directions. Neither did Bảy Thắng, of course, but unlike the Xinguan there was actually something Melendez could do about his predicament. He moved his 6 frigates to focus bombardment on Fan Wenmin. Two of Fan’s ships were small patrol vessels with a paltry 10-gun arsenal, but the third was a turtle-ship. She was built like a floating bunker with a roof over the whole ship that resembled a turtle shell, designed to take heavy fire from pirate ships and fight off boarding attempts. The base design was made by Koreans fighting wokou pirates back in Asia, and it had been improved on by Xinguo-Koreans during the Anti-Piracy War (1553 – 1569). Fan was thus well-protected in his flasgship, but he was outnumbered and outgunned by the six Spanish frigates, each of which had around 30 guns and were thus equal to his turtle-ship in firepower.

For the next two hours, Melendez exchanged cannonades with Fan, focusing fire on the two smaller vessels. At length, the captains of the two ships began wavering. Seeing the damage they were taking, Fan signalled to them with flags that they should fall back a short distance. As the two of them began turning away to withdraw, Melendez saw his chance and seized it. Ordering his frigates forward, he charged the Xinguan battle-line. Both smaller ships hurried to get some distance: once they were far enough away to feel a little safer, one of them turned back to fire a volley at the approaching Mexican ships, but the other made a beeline for North Port. North Port’s commander refused to let the ship into the harbour, but the ship hung around anyway, hoping the Mexicans wouldn’t come too close.

Meanwhile, Melendez surrounded Fan’s sole remaining ship and began blasting her with everything he had. However, the turtle-ship could take far more punishment than Melendez imagined, all while continuing to return fire. At last, Melendez ordered two ships to come alongside the turtle-ship and board her, which they did. It was a tough fight, with Fan firing all guns at point-blank range before the Mexicans got close enough to board. When they finally did get onto the turtle-ship, they had to pause to figure out how to even get inside. Eventually, they blasted several holes in the roof with gunpowder and dropped in.

Vicious close-quarters combat ensued in a space so tight the men resorted to knives, fists, and teeth. Slowly but surely, the Mexicans prevailed, and after an hour Fan Wenmin and a few men were holed up in a room on the gun deck. Whether or not Fan considered surrender is unknown, but the language barrier would’ve made such a thing difficult even if he’d wanted to do so. In any case, the Xinguans had redirected a cannon toward the door. When the Mexicans broke it down, the cannon fired, killing three Mexicans instantly, but the rest poured in and killed all the Xinguans left standing.

In total, only 50 prisoners were taken out a crew of 400-500. The remaining coastal patrol vessel beat a hasty retreat once she saw the turtle-ship being boarded, which left Melendez in command of the sea.

4.6 – The Jaw: The Assault on South Tooth Fort (June 22, 1576)

While Marco Melendez was clearing the Jaw of enemy naval forces, Alonso Flores continued his bombardment of the fort. Wary of assaulting straight away, he was instead probing for weaknesses and hoping to damage the fort’s defences to make an assault less costly. His guns outnumbered those of the fort, and he didn’t have to split his attention as Bảy Thắng did, so Flores was comfortable with waiting a while. From 6 AM until noon, Flores bombarded the defences around the gate. Meanwhile, his men were busy building ladders to scale the walls. Around noon, Flores was satisfied with his gunners’ handiwork. They’d damaged the crenellations around the gate enough to make it hard for the defenders to find cover while his men approached the walls, and had cleared paths through the wooden stakes covering the approaches using a bouncing cannonball technique. At last, he ordered the assault to begin.

The Acapulco Tercio advanced with swords, halberds, pikes, and arquebuses alongside Tlaxcallans, Aztecs, Zapotecs, Mixtecs, and Yopis with spears, macuahuitls, and bows. They advanced at a brisk pace, not so fast as to tire themselves out, but not so slow as to present an easy target. Unfortunately for them, Flores had to order his cannons to cease fire while they advanced up the hill, for fear of cannonballs falling short and hitting his own men, so they had to advance without covering fire.

The defenders were in bad shape. They’d taken a dozen casualties and one of their cannons was out of commission. Still, they were able to set up a firing line along the walls consisting of rocket arrow launchers, fire lances, and crossbows, which rained withering fire on the approaching Mexicans. Mexican arquebusiers and archers stopped at the edge of the outer moat to return fire while the rest of the men picked up the pace. Now sprinting, they crossed both moats and mounted the ladders on the wall, securing them to the ground with ropes tied to iron stakes so the defenders couldn’t push the ladders off. Minutes later, the Mexicans were on the walls. By then, of course, Bảy Thắng had withdrawn his ranged troops and replaced them with melee soldiers wielding swords and axes, as well as an assortment of polearms.

Surely, as his men assaulted the walls of South Tooth Fort, Alonso Flores’s mind must have wandered back to the Battle of Acapulco, which he’d witnessed in his childhood. Back then, 4,700 Mexicans had struggled to hold makeshift barricades against 7,000 Chinese and Xinguan soldiers. This time, Flores was facing a purpose-built fort, but his 7,000 men were only going up against around 480 defenders. Even so, there was nowhere for the defenders to withdraw to, which meant each man had no choice but to stand and fight.

One thing his numbers advantage bestowed, however, was that Flores could afford to fight in more than one place at the same time. While his main force was held up by a stalwart defence over the gatehouse, Flores sent another detatchment to advance on the southwestern corner of the fort. Seeing them coming but having no more melee troops to commit, Bảy Thắng sent his ranged troops to that section of the wall with orders to draw their swords and pin the enemy in place as long as they could. Then, he and his personal retinue of six men, all clad in full suits of lamellar armour, drew their own weapons and stepped into the fray over the gatehouse.

Instead of holding their ground, Bảy Thắng’s ranged troops fled for the mess hall the moment the ladders connected with the wall. Until now, the Xinguans at the gatehouse had held firm, but the sight of their comrades retreating while Mexicans mounted the walls on their flank sent them into a panic. Those who weren’t actively engaged with the enemy fled for the barracks, leaving their comrades in the front line to their fate. Bảy Thắng himself kept fighting until he was brought down by no less than five wounds, and died soon thereafter.

And with that, the Mexicans quickly cleared the walls of the few remaining defenders. There was still a cannon on the tower firing down at the Mexicans on the wall, but Oñate led a squad of soldiers up there, killed the crew, and raised the Cross of Burgundy (Spain’s flag at the time) on the flagpole.

Now, around 100 of the Xinguans remained in the mess hall and barracks, with 500 civilians holed up in the latter. As the Mexicans turned the fort’s own guns on the two buildings and prepared to fire, however, a white sheet was hung out one of the windows of the kitchen, and shortly thereafter, another was hung out one of the barracks windows.

Alonso Flores soon arrived on the scene with his interpreter Benito Aguilar. Aguilar approached first the mess hall, and then the barracks, negotiating with each in turn. Flores offered to let them go if they handed over their weapons, an offer which the defenders accepted. Soon, the 109 remaining Xinguan defenders, now disarmed, marched out of the fort together with most of the civilians. A few civilians volunteered to stay behind to help bury the dead, among whom they had family and friends.

And so the sun set on the Cross of Burgundy flying over South Tooth Fort.

4.7 – The Jaw: North Tooth Fort (June 23, 1576)

As Mexicans and South Provincers fought to the death over South Tooth Fort, they had an audience. A mere mile away, the garrison of North Tooth Fort watched the whole thing go down. They’d had two days to imagine Mexicans marching up the hiking trails on their side of the Jaw and battering down their gates.

However, they had reason to be confident. North Tooth Peninsula’s geography made it a tougher nut to crack. North Tooth Fort was situated on a promontory that jutted out into the Jaw with the land steeply falling away on all sides except a narrow causeway making it accessible from the north. From this position, at a much higher elevation than South Tooth Fort, they could see everything happening in the whole Jaw area, and the range of their guns was greatly increased, while a ship in the water far below would find it almost impossible just aiming at the fort, much less of hitting anything important.

That being said, the commander of North Tooth Fort, a man by the name of Wei Xiangyu, was even less prepared for an invasion than Huế Bảy Thắng had been. He was a brother of Wei Chengjia and uncle of the ruling governor Wei Yonglong. Similarly to Bảy Thắng, he’d used his family connections to get himself a cushy job near the beach where he could attend parties at a friend’s house on the nearby Treasure Island. Unlike Bảy Thắng, however, he didn’t have a sense of duty that kicked in when trouble began.

When a messenger arrived from the fort on June 21st to inform him of the Mexican expedition assaulting their southern neighbour, Wei Xiangyu seemed concerned. He asked how large the expedition was, and upon hearing an estimate of 20-30 ships and perhaps as many as 12,000 men, he retreated into the guest room he was staying in and wouldn’t open the door for the next day and a half. Finally, early in the afternoon of June 22nd, while Flores and Bảy Thắng were trading shots, Wei Xiangyu’s friend had his servants force open the door and went in to talk some sense into him.

At last, around around mid-afternoon, Wei Xiangyu was convinced to return to North Tooth Fort to take command. He went as far as North Port, decided that was close enough, and took up residence in the portmaster’s house and began issuing orders.

There were a lot of problems that simply couldn’t be dealt with. Most of the fort’s southern wall had collapsed in the earthquake of 1573 and fell in the ocean, leaving parts of the fort exposed to enemy fire. With its elevation above its surroundings, however, that didn’t seem like much of an immediate problem, since elevation alone made it nigh-impossible to fire into the fort with 16th-century cannon technology. What was more concerning was the lack of persons to stand on the walls with weapons. Governor Wei Yonglong’s costly war on the Pit River tribes had taken a heavy toll on the available manpower and on the provincial coffers. In fact at that very moment, in June 1576, there was an expedition of 4,000 men marching around the Pit River country chasing ghosts and falling into traps. 150 of those men had been taken from North Tooth Fort, leaving only 350 men and 12 guns to hold a fort intended for a garrison of 1,000 with 40 guns.

Fortunately, the navy wasn’t much use in the conquest of the Pit River, so the bulk of it was still assigned to coastal defence, which meant Wei Xiangyu had 12 ships. 2 were turtle-ships of Korean design, called geobukseon in Korean, while 4 were the less-sturdy castle-ships, called panokseon in Korean. The remaining 6 were Chinese-style war junks. The castle-ships were less sturdy than the turtle-ships, as they lacked the armoured roofing of the latter, but they were still sturdy warships that had proven tough to break during the Anti-Piracy War (1553 – 1569). They were built like a fortress on the water, complete with towers and walls surrounding the main deck and carried 20 guns each. This put Wei Xiangyu’s fleet at rough parity with Melendez’s 16 warships in terms of firepower.

Reaching North Tooth Fort was also made harder by geography. The only good landing spot outside the Jaw was Miwoke Beach, with other beaches being further away. Overlook Beach was relatively close, but it was narrow, providing no space for men to gather or unload supplies as they disembarked. Flores wanted to assault the fort as quickly as possible, so he opted to land at Miwoke Beach with 4,000 men. Nestled in the wooded valley just beyond the beach itself was Miwoke Village, a Xinguan settlement built on the site of an old Miwoke village.

On the heights overlooking both the beach and the village were two blockhouses, which Flores assumed were equipped with cannons that could barrage his soldiers as they disembarked. Indeed, the blockhouses had been designed to accommodate four guns each, but the guns had been taken away in the years since the last pirate attack on the Jaw. Wei Xiangyu, at the suggestion of a subordinate, had ordered 8 guns be stripped from his war junks and taken to the blockhouses, but this would take time. Wei didn’t want to land his ships at Miwoke Beach to move the guns, since that would risk them being attacked by Melendez, so he ordered the guns be taken overland from North Port. Furthermore, he had no draft animals available, which meant the guns had to be hauled by sailors from the ships.

Setting out as the sun was setting on June 22nd, the sailors worked in shifts through the night. On the morning of the 23rd, they managed to reach Miwoke Blockhouse, the first of the two blockhouses, just in time to see the Mexican ships turning toward Miwoke Beach. With no time left to set up the cannons properly, the sailors decided to line them up outside the blockhouse instead.

In short order, the invading ships were anchored near the beach and Mexicans were rowing ashore. When they hit the beach, they came under fire from the line of cannons above. Even so, they were at extreme range, so the cannonfire did little damage. They fired only a few salvos to make their presence known before falling silent again to conserve ammo. This allowed Flores to disembark 1,000 men, whom he ordered to hike up the trail and capture the two blockhouses while the rest of the men and supplies disembarked.

The battle for Quaternary Blockhouse went similarly to the Battle of Blockhouse 1, except that there were more defenders inside but with less firepower and only a handful of grenades. It was soon in Mexican hands.

Now, however, they had to charge uphill against Miwoke Blockhouse, which had 8 cannons lined up outside loaded with grapeshot and ready to cover the entire narrow space of the trail. Flores didn’t want his men to charge into the teeth of such concentrated fire, so while the fighting for Quaternary Blockhouse was still ongoing, he ordered 30 men to scale the cliff between Miwoke Beach and Miwoke Blockhouse. There, they were to await the signal to attack. It was a difficult climb but not insurmountable, and it was partially forested, which gave the men both cover and concealment as they climbed. They were a mix of sword-and-buckler men from the tercio and auxiliaries with macuahuitls and bows. Once they reached the treeline, they waited.

When Quaternary Blockhouse was captured, Flores gave the order and one of his ships fired a single cannon. 30 men leapt out of the trees behind Miwoke Blockhouse and stormed it. The door had been left open for the gun crews to retreat into if need be, so the Mexicans flooded the blockhouse and killed its defenders before they even knew what was going on. The gun crews heard the screams of dying men, but couldn’t tell what was happening. However, the quick-thinking commander of the battery concluded that they’d been outflanked somehow. He ordered his men to spike the guns, rendering them useless to the Mexicans, and retreated toward Last Blockhouse.

Only once they saw the gun crews retreating did the vanguard at Quaternary Blockhouse advance. Passing Miwoke Blockhouse, now safely in friendly hands, they immediately moved on to Last Blockhouse, where the defenders fired a single, massive volley of rocket arrows before abandoning the blockhouse and retreating across the causeway to North Tooth Fort.

Flores spent the rest of the morning and part of the afternoon moving the rest of his men and supplies up to Last Blockhouse, including 12 of his artillery pieces.

With the fall of Last Blockhouse, Wei Xiangyu was now cut off from the fort. As he considered his next move, a small party of Mexicans crested the hill overlooking North Port and waved a white flag. Wei Xiangyu sent his naval commander, Wei Xiaojia, to negotiate on his behalf. Despite sharing a family name, Xiangyu and Xiaojia were of no relation to each other, Wei is simply a common Chinese surname. Wei Xiaojia was sent because he spoke Nahuatl and a little Spanish, which he’d learned during his time escorting North Province merchants travelling between Acapulco and Ningbo in the 1560s.

Xiaojia and a small party climbed the hill to meet with the Mexicans, who signalled to Flores and Aguilar to come down from Last Blockhouse. When everyone was present and introductions had been exchanged, Flores opened negotiations thusly:

“As you can see, my armada is quite large. We have come to bring the rule of our king to these lands, but we have no reason to quarrel with you northerners. I have a simple offer for you. Abandon your fort and your port and we will not hinder your withdrawal. You may march out in armour with all your weapons and banners, only leave us the fortress and the port and you will come to no harm.”

Surprised by the leniency of these terms, Wei Xiaojia inquired as to the time frame for the withdrawal. Flores replied that they should be marching out of the fort before the sun was fully risen the next morning, and be sailing out of the port no later than noon.

These terms were relayed to Wei Xiangyu, who accepted them immediately. He sent orders to the garrison of North Tooth Fort to begin the evacuation. At noon on June 24th, 1576, Wei Xiangyu and Wei Xiaojia sailed out of North Port with the garrisons of North Tooth Fort and North Port, as well as all the civilians, and as much stuff as they could carry. Everything else was destroyed, including the cannons of North Tooth Fort, which were pushed off the cliff into the ocean.

[Next]

Leave a comment